Monkeypox is spreading, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants continue to emerge, and there are fears of polio resurgence. It does not end there, 2022 has now presented a novel zoonotic virus known as “Langya henipavirus” (LayV).

LayV was identified during a sentinel surveillance programme in three hospitals in eastern China between April 2018 and August 2021, which included febrile patients with recent animal exposure. Subsequently, 35 patients, mostly farmers, from the Shandong and Henan provinces of eastern China have been diagnosed with LayV. The virus was formally described in the New England Journal of Medicine on 4 August 2022.

Isolation and characterisation of LayV

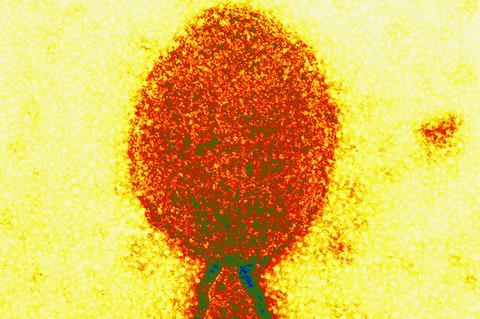

LayV was identified through metagenomic sequencing of a throat swab sample taken from a 53-year-old female farmer. The virus was named after Langya, a rural town in Shandong where she was from. Genomic analysis revealed that LayV is closely related to the Mojiang henipavirus which was first isolated from yellow-breasted rats (Rattus flavipectus) residing in an abandoned mine in the southern Chinese province of Yunnan in 2012. Henipaviruses belong to the Paramyxoviridae family of single-stranded, negative-sense RNA viruses, a class which includes Hendra- and Nipah virus, both of which are bat-borne (Pteropid spp.) and can be fatal in humans. Most cases are associated with animal contact, although for Nipah virus limited human-to-human transmission may occur. The Mojiang henipavirus differs in its mechanism of cell entry from the Hendra- and Nipah viruses and has not been found in humans.

Potential hosts

To determine potential animal hosts of LayV, researchers tested domestic animals, as well as 25 species of small wild animals. LayV antibodies were detected in 2% (3 of 168) of domestic goats and 5% (4 of 79) of dogs but were most prevalent in wild shrews (27%; 71 of 262) leading the team to conclude that these small mammals may be a natural reservoir for the virus. It remains to be established whether the virus is transmitted directly from shrews or via another intermediate host.

Should we be concerned?

In contrast to Hendra- and Nipah virus, no deaths have been reported in those infected with LayV and cases are not thought to be linked. Contact tracing was performed on nine patients and 15 of their close contact family members. Transmission was not reported, indicating that human infections may be sporadic. Given the small sample size, however, human-to-human transmission cannot be ruled out and ongoing surveillance is crucial to identify additional cases. Notably, of the 35 cases, 26 patients were infected with LayV only. Reported symptoms among those without a co-infection were comparable to those of influenza and included fever (100%), fatigue (54%), cough (50%), loss of appetite (50%), muscle ache (46%), nausea (38%), headache (35%), and vomiting (35%). Pneumonia, a more serious complication, was diagnosed in four patients and was associated with a higher serum viral load compared with those without pneumonia. Other abnormalities included a reduction in platelets (35%) and white blood cells (54%), and impaired liver (35%) and kidney (8%) function.

Zoonotic spillover, the transmission of pathogens from animals to humans, is a relatively rare event, and it is important to note that most microorganisms are not pathogenic to humans. The COVID-19 pandemic however appears to have raised the level of concern associated with zoonotic events, and the known zoonotic transmission of other henipaviruses raised concerns over LayV.

Are treatments or vaccines available for Henipaviruses?

Due to its recent discovery, there is no approved treatment against LayV - this is also the case for Hendra- and Nipah virus infections for which the standard treatment is supportive care for respiratory and neurological complications.

A commercial Hendra virus vaccine for horses (the most commonly infected domestic species) was recently licensed in Australia, and antivirals, monoclonal antibodies and vaccines are currently under evaluation for the management of Hendra- and Nipah virus infections in humans. In the future, these developments may offer options for the treatment and prevention of LayV infection.

Surveillance measures

The detection and identification of pathogenic viruses has been revolutionised by the development of molecular techniques, particularly polymerase chain reaction (PCR) coupled with next generation sequencing technology. The discovery of LayV highlights the continuous risk of the emergence of (new) pathogens and underscores the importance of genomic sequencing and the implementation of surveillance as a critical tool for early response. Evidently, sentinel surveillance programmes are an effective public health tool and often require fewer resources than population-based surveillance methods.

No comments yet