The so-called ‘Age of Discovery’ was a period of exploration, exchanging new foods, gold and culture. However, with the exchanges between Europe and The Americas, there was also the exchange of pathogens with native populations.

What may have caused a slight cough and cold or to Europeans was deadly to others. Imported diseases brought to shores by explorers caused widespread epidemics across the Americas. Changes to the demography of indigenous populations were not only consequences of British and European colonial invasion through war. What may have had the most significant effect was disease. This article will focus on a small part of the history of the post-Columbian epidemiology of the Americas to dissect the impact of European diseases on indigenous populations.

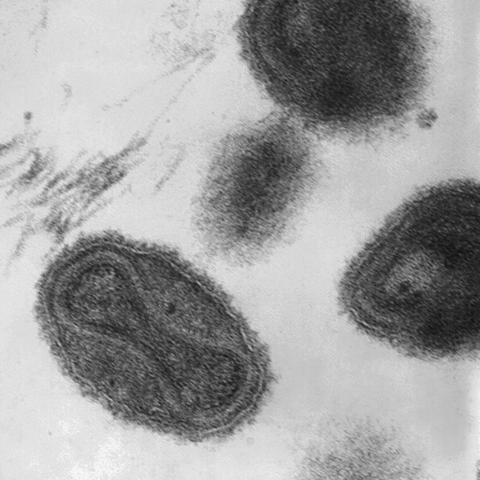

Virgin soil epidemic is a phrase coined by Alfred W. Crosby in 1976, describing native populations as being at risk of contracting disease due to disease absence from the area for multiple generations. Immunologically defenceless, when faced with imported disease from explorers, virgin soil epidemics have the power to wipe out native populations. This term is not only valid for The Americas but also for the rest of the world. Indigenous communities could be vulnerable to disease when introduced from Europe; for example, smallpox, flu, measles and typhus. Their vulnerability may have been caused by various factors – including no natural childhood exposure, which led to a lack of antibodies against European diseases in adulthood.

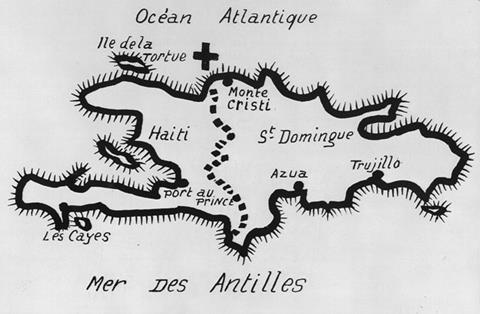

Between 1492 and 1504, Christopher Columbus and his crew sailed across the Atlantic Ocean, completing voyages exploring the Caribbean (including Hispaniola and Guanahani) and Central and South America. Maritime navigation bridged land that was oceans apart, creating a safe passage for pathogens from one continent to another. These expeditions facilitated human interaction between the European explorers and native populations, and these interactions drove the transmission of European pathogens into new communities. In addition, the importation of animals from Europe to the Americas had a devastating impact; these animals were havens for harbouring zoonotic pathogens that caused diseases such as swine flu, typhus and the bubonic plague.

Whilst the records of indigenous populations from the pre-Columbian era are incomplete, and thus, we may never know the true devastation caused, researchers have estimated that The America’s population varied between 8 million and 110 million natives. Despite this, historian Noble David Cook approximated that the minimum devastation seen was an 80% loss of indigenous communities and up to total extinction of certain populations.

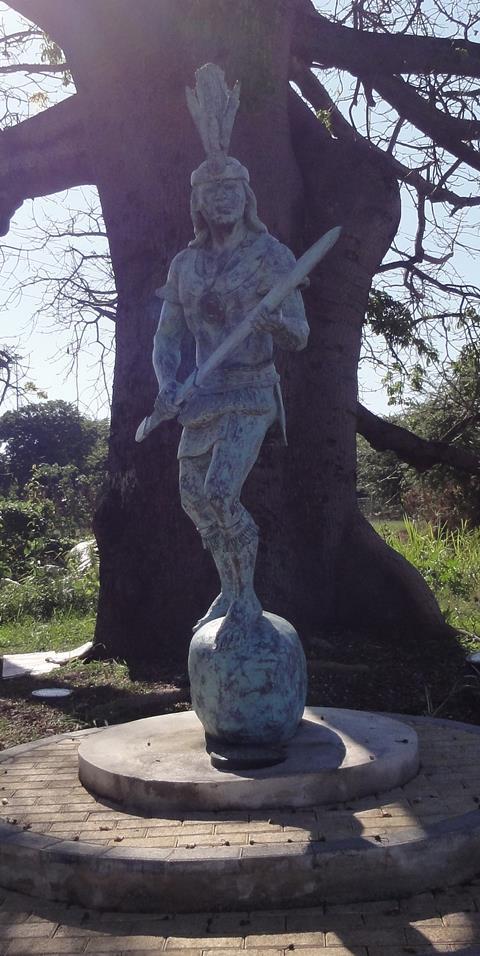

There are some early recordings of settlement numbers for the island of Hispaniola (or Quisqueya). Census recordings in 1508 estimated a population of 60 thousand indigenous Taíno people, and by 1516, a population of 23,000. Smallpox is believed to have been introduced to the Hispaniola population around this time (~1518), owing to evidence from old journals and paintings from the communities. With a mortality rate of around 50%, the virus often destroyed whole communities at a time. Smallpox was a childhood disease in Europe. However, a disproportionate number of smallpox casualties in The Americas territories were adults due to their lack of immunity against newly emerging diseases. Highly virulent diseases such as smallpox, influenza, and measles affected whole communities as they were easily transmissible.

In addition, zoonotic diseases from swine and rats were transported aboard European ships. In 1493, swine flu was brought to The Americas by Columbus, who imported eight sows from the Canary Islands. The domesticated animals were of epidemiological significance as the sows rapidly multiplied on the island of Hispaniola. The first Spaniard settlement was a village Columbus named La Isabela, which became the outbreak’s epicentre. Columbus, Bishop Las Casas, and Alvarez Chanca are just a few individuals who documented detailed accounts of the winter epidemic of 1493 after Columbus’s second voyage to the Americas, which helped characterise the epidemic as swine flu centuries later. They described symptoms aligning with influenza; a highly contagious transmission, fever, general malaise and high mortality rates across the Spaniards and native community. Pre-Columbus, The Americas had few domesticated animals, which meant that indigenous communities had no built-up immunity against diseases harboured in domestic animals, such as influenza. Introducing these animals to the Americas left natives vulnerable to zoonotic disease, leading to high morbidity and mortality from swine influenza.

Due to the absence of medical records and documentation, we will never know the true magnitude of demographic collapse in The Americas post-Columbus. However, it is clear that European settlers brought to the region infectious diseases which their immune systems were not prepared for. The transfer of disease across the ocean is believed to be a major contributor to allowing Spanish conquistadors to take over the Americas, rather than relying on fighting and weapons alone. This leads to the questions, how big of a contributor was infectious disease in the European colonisation of The Americas?

No comments yet