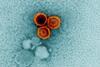

A small number of HIV-infected cells remain in the tissues of people living with the virus and undergoing antiretroviral therapy. These viral reservoirs, major obstacles to the cure of HIV, have long been known to exist.

Until now, however, it wasn’t clear which organs the virus prefers to hide in.

A team from the Canadian HIV Cure Enterprise (CanCure) led by Université de Montréal immunology professor Nicolas Chomont, a researcher at the CHUM Research Centre (CRCHUM), has succeeded in identifying these hidden places, opening the way to targeting them for future therapies.

In a study published in the journal Cell Reports, the scientists reveal that genetically intact viruses, responsible for viral rebound if antiretroviral therapy is interrupted, are concentrated in the deep tissues of the spleen and lymph nodes, organs of the immune system.

Post-mortem analysis

“We owe these results first and foremost to the generosity of two Canadian men (in Ottawa and Edmonton) who were at the end of their lives, living with HIV and on antiretroviral therapy,” said Chomont.

“By donating their bodies to science, these men made a unique contribution to our work. It is extremely rare to have access to post-mortem analysis to test for the presence or absence of viral reservoirs in so many organs of the same human body – about 15, in this case.”

Caroline Dufour, a doctoral student in Chomont’s laboratory at the CRCHUM and the lead author of this study, developed ultra-sensitive methods of analysis to locate the body’s preferred hiding places for viral reservoirs.

Using a protocol for analyzing the few viral genomes persisting in tissues, she was able to identify the organs in which “live” HIV preferentially hides.

Intact viruses

“In the Ottawa donor, genetically intact viruses were concentrated in the lymph nodes and spleen,” said Chomont. “In the tissues of the Edmonton participant, they were found predominantly in the same organs, although lower concentrations could also be detected in other tissues.”

Thanks to her analyses, Dufour was also able to demonstrate that distant organs, such as the cells of an axillary ganglion (in the armpit) and those of an inguinal ganglion (in the groin), could harbour identical intact HIV genomes.

“This finding suggests that the infected cells harbouring these ‘dormant’ viruses have the ability to travel throughout the body and to change organs, even with antiretroviral therapy in place,” said Chomont. “The reservoir is therefore very dynamic, much more so than we had thought.”

This recirculation of infected cells in the body provides an undeniable therapeutic advantage. Away from their deep tissue hiding places, they are now more readily visible to the immune system and thus susceptible to attack and subsequent elimination.

Chomont’s team currently holds tissue samples from a third Canadian donor. The team is counting on further body donations to launch analyses aimed at determining specifically in which part of the body the virus is most active.

No comments yet