Not one, but two promising new vaccines are likely to be introduced to the UK, yet routine childhood vaccination rates have been decreasing for ‘old’ diseases like measles and polio - what’s going on?

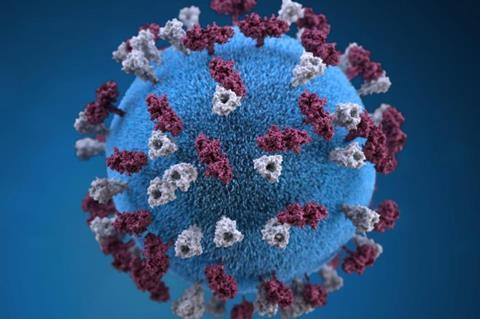

We are at the dawn of a new era of tackling infectious diseases, with several new vaccines against old diseases coming to the fore. One such infection is that caused by respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which can be responsible for fatal lung infections in infants and the elderly like bronchiolitis.

Following six decades since its discovery, RSV now has not one but two very promising vaccines which are likely to be introduced to the UK. And mRNA vaccines, such as those used for COVID-19, are helping to combat more diseases . Furthermore, there’s even the hope that vaccines could be used against bacteria that are resistant to many of our antibiotics.

However, with routine childhood vaccination rates decreasing for old diseases like measles and polio, one stumbling block is how we are going to vaccinate with these new vaccines when we can’t even vaccinate with the old tried and true vaccines that we’ve had for decades? Perhaps if we understood what was happening, then we could ensure adequate roll out.

Halting old and new diseases

The human population has been plagued by disease for millennia, many of them caused by infections with viruses. These diseases, like smallpox, polio, and measles, exerted a devastating toll, and continued to do so right up until the 20th century. It’s likely that hundreds of thousands of people died or were left permanently damaged by these infections.

In more modern times, as we learnt how diseases were spread, discovered the link to good hygiene and developed antibiotics, death tolls decreased. However, vaccination played an integral part in controlling – and in the case of smallpox – eradicating the virus and the disease from the wild.

With modern vaccines being developed in the mid-20th century, numbers of polio and measles cases and deaths plummeted, and these infections were eliminated from a large part of the globe. Vaccination against these viruses has been so successful that it is possible that both measles and polio could be eradicated from the human population. Indeed, vaccination of cattle helped eradicate an animal virus cousin of measles called rinderpest.

As we learned more about how vaccination worked, we were able to develop better and safer vaccines much faster than before, such as viral vectored vaccines or mRNA vaccines. Shortly after the Covid-19 pandemic began, several vaccines were licensed to protect against infection, disease and death.

Vaccination dwindling

Unlike smallpox, the other human viruses we vaccinate against do still circulate in people across the globe. From these refuges, wild measles and polio can attempt to enter and spread in other countries from which they had been eradicated. Recently, detected by wastewater surveillance, poliovirus was spreading in the UK. However, in the UK these viruses have a harder time establishing themselves, due to the initially small number of infections, random nature of transmission and built-up immunity they encounter. This immunity has been generated through vaccination campaigns.

For measles at least, this is as close to herd immunity as we can get. For a virus like measles, virus herd immunity requires 95% of a population of people to have protective antibodies against the virus. However, although in the UK, for example, vaccination is free at the point of care and straightforward to access, not everyone gets vaccinated. Some people cannot get vaccinated and in some, the vaccines simply won’t work due to some deficiency in their immune system. Gaps in herd immunity can provide safe places for the viruses to circulate or for diseases and deaths to show up.

Thankfully, the UK closely monitors vaccination, and we know that the majority (>80%) of children get vaccinated against a range of diseases including measles, mumps and rubella. However, these numbers are not uniform across the geographical area, with London showing a 10% drop in vaccination rates on average, and Northern Ireland slightly lower than Wales or Scotland.

Additionally, rates are not uniform across time either, with most vaccines showing a slow but steady reduction in rates early 2010s (by a few percentage points). Critically, these values are already lower than the threshold for herd immunity and point to the potential for localised outbreaks to occur more frequently in the future.

We don’t know all the reasons why vaccination rates aren’t 100% nor why they are decreasing. The reasons why are likely several-fold. Vaccination may not reach certain demographic sections of the community with high levels of social deprivation. Vaccination may not be an easy decision for everyone all the time and there are genuine safety concerns (although these are usually very rare or minor) and cost-benefit analyses to consider.

Additionally, antivaccination campaigns can prey on those people who are already vaccine-hesitant, making it less likely that they vaccinate their children. And there is the potential that people’s experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic, particularly vaccine mandates and vaccine safety concerns, may make them less likely to vaccinate against other diseases. However, these rates had been declining before the pandemic, and conversely, the pandemic showed the power of vaccines in helping to combat disease.

New vaccines

Where, then, does that leave us as regards vaccines old and new, like RSV for children? It is clear that many diseases continue to contribute to a great health burden on society - and this could possibly get worse. It is equally clear that in many cases (old and new) vaccines can or will be able to alleviate some of that burden.

Despite developing safe and effective vaccines, significant issues in getting those vaccines into people exist. But by understanding those drivers, we can address them and ensure that people and communities are protected. To overcome these hurdles, we must continue to communicate the real impact of diseases and talk about the benefits that vaccination can bring alongside a fair discussion of their risks. Finally, we should capitalise on the success of vaccines during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dr Connor Bamford is a Lecturer and Group Leader in Virology and Antiviral Immunity at the School of Biological Sciences & Institute for Global Food Security at Queen’s University Belfast, where he is researching immunity to viruses and bacteria in the lung and the role that specific cytokines, known as ‘interferons’ play, with the hope of identifying novel ways to block infections.

No comments yet