Adding carbon-rich materials such as biochar and hydrochar to farmland soils is often seen as a promising way to fight climate change. But a new study from Finland shows that the type of char used can make a big difference in whether the soil releases or stores greenhouse gases.

Researchers from the Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke) and collaborating universities tested how biochar and hydrochar, combined with nitrogen fertilizer, affected greenhouse gas emissions, soil carbon pools, and crop yield in a typical boreal legume grassland. Over a three-month experiment, they measured emissions of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane from soils growing timothy grass and red clover.

READ MORE: Biochar and plants join forces to clean up polluted soils and boost ecosystem recovery

READ MORE: Biochar shows big promise for climate-friendly soil management

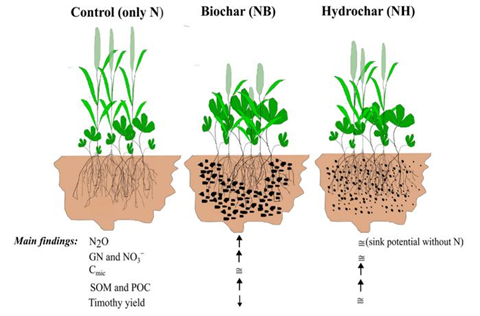

The team found that biochar and hydrochar influenced soil processes in opposite ways. Biochar, produced by high-temperature pyrolysis of birch wood, tended to increase nitrous oxide emissions, a potent greenhouse gas linked to fertilizer use. In contrast, hydrochar, made by lower-temperature hydrothermal carbonization of birch bark, suppressed nitrous oxide release and in some cases even turned the soil into a small nitrous oxide sink.

“These findings show that not all chars behave the same way,” said lead author Hem Raj Bhattarai of Luke. “Hydrochar appears to promote soil processes that remove nitrous oxide, while biochar can stimulate microbial activity that produces it.”

Organic matter

Both char types significantly increased the amount of particulate organic carbon in the soil, helping to build up organic matter. However, they had little effect on total carbon dioxide and methane fluxes or on the overall biomass yield of the grass-clover mixture. Interestingly, biochar with nitrogen fertilizer slightly reduced the yield of timothy grass, suggesting that it might limit nitrogen uptake in some conditions.

The study, published in Biochar, also found that hydrochar supported higher microbial biomass carbon than biochar, indicating a more active soil microbial community. This difference, the researchers say, may help explain why hydrochar reduced nitrous oxide emissions.

“Our results highlight the complex interactions among soil microbes, vegetation, and nitrogen management,” Bhattarai said. “Selecting the right char type for a specific soil and crop system is essential if we want to use these materials to improve soil health and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions.”

The authors suggest that future studies should examine char effects at the field scale and across different soil types to better guide sustainable agriculture in northern regions.

No comments yet