On 19 June 2022, Iraq’s health authorities announced a cholera outbreak after at least 13 cases were confirmed across the country and thousands of hospital admissions for acute diarrhea were reported. As of 28 October 2022, Iraq has reported over 1000 confirmed cases of cholera, with five associated deaths.

For centuries, war has catalysed the spread of infectious diseases, creating the ideal conditions for bacteria and viruses to tear through armies and civilian populations. In September 2015, a cholera epidemic began in Iraq, starting the latest in a long line of diseases to bring war-torn populations to their knees.

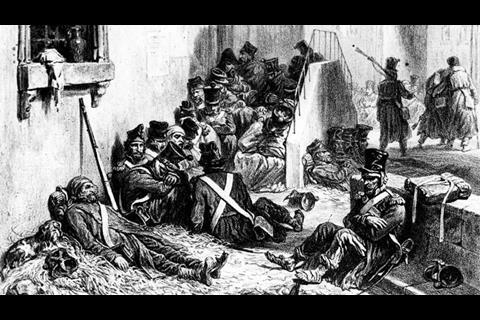

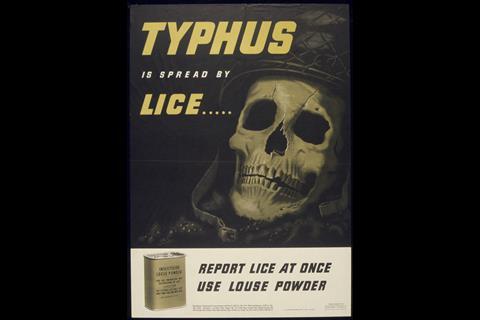

Combat-fueled epidemics can be traced back to ancient Greece: the Plague of Athens, which is thought to have been epidemic typhus, returned three times during the Peloponnesian War, in 430 BC, 429 BC and 427-6 BC. Typhus has made an appearance in several wars since, notably during the English Civil War, the Thirty Years’ War and the Napoleonic Wars. Famously, more soldiers died of typhus than were killed by the Russians during Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow in 1812. Epidemic typhus also killed hundreds of thousands of people during World War II, infecting prisoners in Nazi concentration camps.

Cholera is also notoriously infectious. Starting in 1817, the disease travelled along the Ganges in India, killing hundreds of thousands of people; the British army alone reported 10,000 deaths. The disease had been carried port to port in kegs of water and the excrement of infected people. A decade after the epidemic started, cholera had become the most feared disease of its time.

During the American Civil War, 600,000 soldiers died, two-thirds of whom succumbed to infectious diseases. According to a review of medical records kept during the war, bad sanitary practices were to blame for the spread of disease; one commander dismissed inspectors’ complaints, saying “an army camp is supposed to smell that way.” Doctors persevered and eventually their plea for better sanitation resulted in a decrease in the incidence of enteric diseases later in the war.

Although much has changed over the centuries, some constant aspects of warfare mean that conflict still provides the ideal conditions for epidemics to occur. Sanitation is one contributing factor, especially in refugee situations, where hygiene may not be ideal in camps. Infrastructure is often damaged, making it more difficult for people to seek medical care. The widespread deforestation and damage to infrastructure that occurred during the Vietnam War is thought to have led to a plague epidemic in the 1970s.

Movement of people also has a major impact on disease epidemiology. Soldiers move around, carrying equipment and diseases with them. Displaced people and migrants who move because of conflict can also hasten the spread of disease, either by taking disease with them to new places or by contracting diseases they have no immunity to. Today’s widespread migrations are only serving to facilitate the spread of infection, the results of which are all too apparent in Iraq.

Cholera outbreaks in Iraq

This epidemic was not the first time Iraq has been hit by cholera. On 15 September 2015 the WHO received notification that there were confirmed cases of cholera in five Governorates in Iraq: Baghdad, Babylon, Najaf, Qadisiyyah and Muthanna. One week later the number of laboratory-confirmed cases had risen to 120. In three weeks, this rose to more than 1200 cases of Vibrio cholerae 01 Inaba.

In 2007, there were more than 4500 cases of cholera in Baghdad, with three deaths. The infectious agent was confirmed as Vibrio cholerae 01 Inaba. Complicating the epidemic further, the strain was resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

In a paper published in the Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal in 2010, epidemiologists noted the connection to sanitation and called for action: “Efforts are needed in Baghdad to establish safe drinking-water and proper sanitation as limited availability of tap-water and sewage contamination probably contributed to the spread of the disease.” Five years later, the epidemic was threatening to reach similar levels.

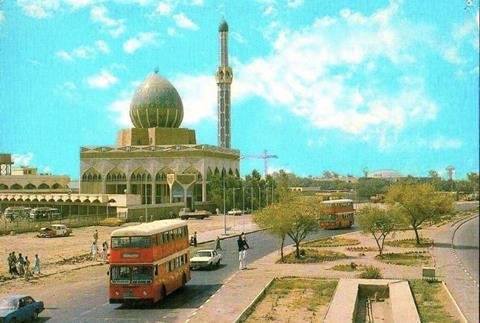

One of the reasons for this was the sustained conflict in the country and the lack of coordination in the effort to improve health. In the article “Living conditions in Iraq: 10 years after the US-led invasion,” S Rawaf et al. noted that in the decade since the US invaded Iraq, the country had deteriorated in terms of people’s health, among other things.

“In the early 1980s, Iraq was a middle-income and rapidly developing country with a well-developed health system,” said the authors. Three decades later – after wars, sanctions and a violent sectarian upsurge – child and maternal health indicators have deteriorated and diseases such as cholera have remerged.

Despite efforts to improve the health system in Iraq, political deadlock and complex economic challenges continue and health indications have not improved. The impact of COVID-19 has had a significant socio-economic impact on the Iraqi population as a whole and have exacerbated humanitarian needs. Basic hygiene needs are still not being met, broken-down water supply systems and insufficient chlorine to clean water are ripe conditions to fuel cholera epidemics.

Responding to the epidemic

Such a rapid rise in cases required a concerted effort to halt the spread. According to a report issued by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), emergency responses were focused on eight areas: protection; water, sanitation and hygiene; health; shelter and non-food items; food security; camp coordination and management; education; and logistics.

To help contain the epidemic, the WHO and UNICEF have led responses to strengthen laboratories with water testing and sampling instruments, and improve water hygiene throughout the country by distributing bottled water, hygiene kits and chlorine tablets.

Since sanitation is one of the major factors contributing to the spread of cholera, there is also a focus on improving sewage systems, with septic tanks being disinfected, water treatment plants being fixed and solid waste disposal being improved. Public health messages are also vital in the control of an outbreak. Control teams use social media, radio, text messages and even door-to-door campaigns to share information about how to prevent cholera infection.

Years of war and neglect in Iraq have resulted in broken water and sanitation systems and a series of deadly epidemics. Ultimately, control efforts can only go so far; as long as people are displaced and infrastructure is broken, the conditions will be ideal for more outbreaks of diseases like cholera.

Unfortunately, if the people in power do not recognise and address the problems contributing to the spread of disease, a permanent solution is unlikely to be found.

Cholera

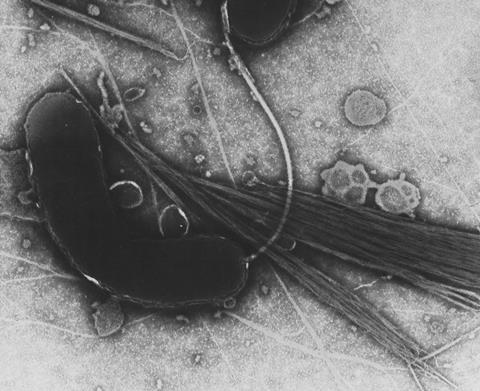

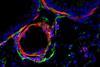

Cholera is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, which is transmitted via water; poor sanitation and unclean water supplies mean cholera can spread through populations quickly. Cholera is an extremely virulent acute diarrhoeal disease that can kill adults and children within hours of infection. There are several different serogroups of V. cholerae, two of which – O1 and O139 – can cause outbreaks.

There are an estimated 1.3-4 million cases every year worldwide, causing 21,000-143,000 deaths. Around 80% of people infected do not develop symptoms, but they are able to shed the bacteria in their faeces and contribute to the spread of the disease.

Despite its virulence, cholera can be prevented with provision of clean water and good sanitation. Following infection as many as 80% of cases can be treated successfully and simply, using oral rehydration salts. Oral vaccines are also available against cholera, and some countries have vaccinated high risk populations. However, the WHO recommends that more long-term actions are taken: “In the long term, improvements in water supply, sanitation, food safety and community awareness of preventive measures are the best means of preventing cholera and other diarrhoeal diseases.”

In 2017, the World Health Organization launched a global strategy for cholera control, Ending Cholera: a global roadmap to 2030.

1 Reader's comment