While popular culture commonly depicts extraterrestrial life as little green men with large, oval-shaped heads, it’s most likely that if there is life beyond our planet and within our solar system, it is microbial.

Recently, NASA awarded University of Massachusetts Amherst microbiologist James Holden $621,000 to spend the next three years using his expertise to help predict what life on Jupiter’s moon Europa might look like. For that, Holden turned to an unexpected place: the volcanoes a mile beneath our own oceans.

READ MORE: Efforts to find alien life could be boosted by simple test that triggers microbes

READ MORE: Signs of life potentially detectable in single ice grain emitted from extraterrestrial moons

Jupiter’s moon, Europa, has a frozen surface, but astronomers believe that beneath all that ice lies a salty, liquid ocean that is in contact with a hot molten core.

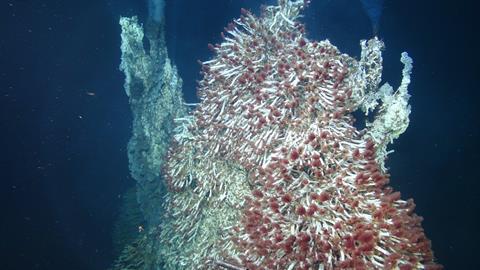

“We think, based on our own planet, that Europa may have conditions that can support life,” says Holden, who points to the hydrothermal vents deep beneath our oceans’ surface. In fact, NASA’s recently launched Europa Clipper satellite is expressly designed to ascertain how habitable Europa may be.

Deep-sea vents

Holden has spent his entire academic career studying the deep-sea vents that may be key to alien life. “I’ve been looking at deep-sea volcanoes since 1988,” he says. “To get our microbes from them, we use submarines—sometimes human-occupied, sometime robotic—to dive a mile below the surface and bring the samples ashore and back into my lab at UMass Amherst.”

Holden has built a lab that can reconstruct the lightless, oxygen-less conditions that these specialized microbes, which get their energy solely from the gases and minerals spewing out of the vents, love. “Because Europa’s conditions might be similar to the conditions these microbes come from,” Holden says, “we think that Europan life, if it exists, should look something like our own hydrothermal microbes.

“We have long had a basic interest in knowing if there is life beyond our planet and how that life would function,” Holden adds. “It’s exciting to think that the answer to the secret might be here on our own planet.”

Life on Europa

But Europa is not Earth, its oceans are not ours and if microbial life does exist there, it probably doesn’t look exactly like ours.

“So, we need to figure out the different chemical processes that Europan microbial life might be using in order to create energy,” Holden says. “Different chemistries could create very different kinds of microbes.”

The hydrothermal microbes on Earth that Holden studies get their energy by breaking hydrogen down using special enzymes called hydrogenases. But there are different kinds of hydrogenases, they work in different ways and may have different functions in different kinds of cells.

Organisms that rely on different sets of hydrogenases may look and function very differently from each other. Furthermore, iron, sulfur and carbon coming from the vents are all adept at partnering with hydrogen by accepting its electrons to generate energy, but scientists aren’t yet sure exactly how those processes work biologically, especially as the amounts of hydrogen vary. “Our research will be to determine how the different chemical process contribute to an organism’s physiology,” says Holden.

No comments yet