Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide and often originates in atherosclerosis, a chronic condition in which inflammation and fat deposits cause arteries to harden and narrow. Although clinical practice already targets causal factors like cholesterol, hypertension, and smoking, detecting atherosclerosis in its early stages remains challenging.

A new study led by the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) and published in Nature has identified a gut microbiota–derived metabolite, imidazole propionate (ImP), that appears in the blood during the early stages of active atherosclerosis. The study has received support from the ‘la Caixa’ Foundation through its CaixaResearch Health Research Call, with €967,620.20 in funding.

READ MORE: Scientists discover how the gut modulates the development of inflammatory conditions

READ MORE: Consuming fermented food natto suppresses arteriosclerosis

Blood marker

Mastrangelo emphasizes that the discovery has important clinical implications: “Detecting this blood marker offers a major advantage because current diagnostic tools rely on advanced imaging techniques that are complex, expensive, and not covered by public health systems. Blood levels of ImP provide a diagnostic marker that could help identify apparently healthy individuals with active atherosclerosis, and thus enable earlier treatment.”

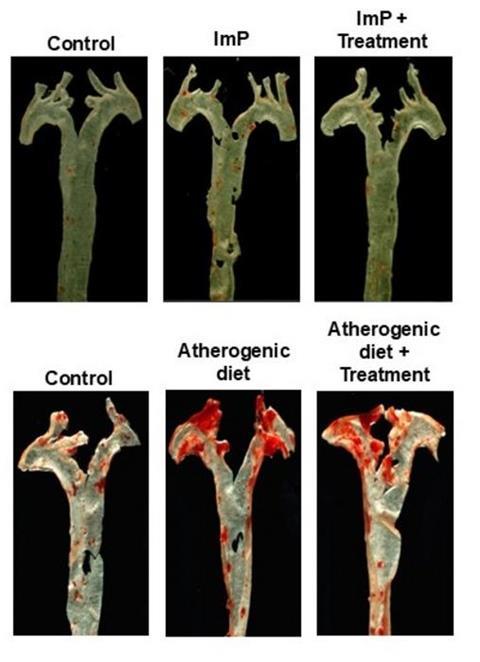

But the discovery goes even further. Co–first author Iñaki Robles-Vera explains: “We not only observed elevated ImP levels in people with atherosclerosis, but also showed that ImP itself is a causal agent of the disease. In animal models of atherosclerosis, ImP administration led to the formation of arterial plaques. It does this by activating the imidazoline receptor type 1 (I1R), which increases systemic inflammation and promotes atherosclerosis development.”

David Sancho, head of the CNIC Immunobiology Laboratory and lead author on the study, notes that “this discovery is important because it opens the way to a completely new line of treatment.”

Slows disease progression

The study shows that blocking the I1R receptor prevents ImP-induced atherosclerosis and slows disease progression in mouse models fed a high-cholesterol diet. “This suggests that future treatment could combine I1R blockade with cholesterol-lowering drugs to produce a synergistic effect that prevents atherosclerosis development,” explains Sancho.

“These findings open new possibilities for the early detection and personalized treatment of atherosclerosis,” he continues. “Instead of focusing solely on cholesterol and other classic risk factors, we may soon be able to analyze blood for ImP as an early warning signal. At the CNIC, we are also working to develop drugs that block the detrimental effects of ImP.”

The CNIC-led study was conducted through extensive collaboration with researchers at multiple national and international centers: Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, USA); the Fundación Jiménez Díaz Health Research Institute; the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid; the Spanish cardiovascular research network (CIBER-CV); the University of Gothenburg (Sweden); the University of Athens (Greece); Inmunotek S.L.; the University of Michigan (USA); Hospital de La Princesa; the Center for Metabolomics and Bioanalysis (CEMBIO); the Universidad San Pablo-CEU; the University of Heidelberg (Germany); and the Sols-Morreale Biomedical Research Institute (IIBM-CSIC).

The study was supported by funding from the European Research Council (Consolidator and Proof of concept grants), Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities; the Spanish State Research Agency; the European Union’s NextGeneration funding mechanism; and the “la Caixa” Foundation.

No comments yet