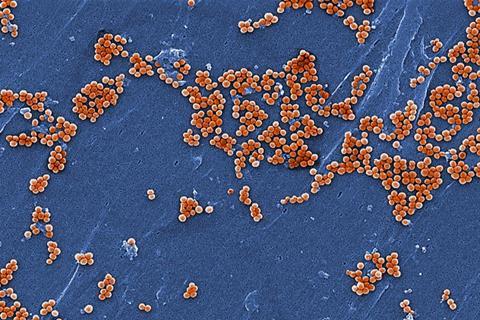

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is an increasingly dangerous problem affecting global health. In 2019 alone, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) accounted for more than 100,000 global deaths attributable to AMR.

A major challenge in diagnosing and treating AMR is that its evolution can outpace clinical decision-making. Traditionally, identifying AMR in S. aureus involves culturing samples of the bacteria in the presence of various antibiotics. While reliable, this lab-based approach takes time, with results potentially coming back after a treatment has been selected, which could exacerbate AMR. Previous machine-learning approaches have relied on highly detailed genomic profiles, which may fail to account for novel strains or poorly sequenced genomes.

In a new paper published in npj Antimicrobials & Resistance, researchers from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) propose robust machine-learning models for predicting specific AMR profiles based on the given bacterium’s genome. “Delays in diagnosing antibiotic resistance can affect treatment decisions,” says first author PhD candidate Bruna Fistarol. “Experiencing this first-hand motivated me to explore genomic approaches that could enable faster diagnostic tools.”

Practical signal

Rather than chasing thousands of minute DNA ‘spelling changes’ in the exhaustively sequenced and annotated genomes of each bacterial strain, the team chose a simpler and more practical signal: which genes a strain carry, and how many copies it has. They trained machine-learning models on a large, worldwide database of S. aureus genomes to predict AMR to commonly used antibiotics.

READ MORE: Fungi set the stage for life on land hundreds of millions of years earlier than thought

READ MORE: Students tackle drug resistance by teaching machine learning

“The approach proved to be highly accurate, and crucially, the models remained reliable even when applied to genetically distinct strains not previously encountered,” says Professor Gergely J. Szöllősi, senior author and head of the Model-Based Evolutionary Genomics Unit at OIST. “And because gene-content information can be recovered even when sequence data are messy or incomplete, these models hold significant promise for real-life clinical contexts.”

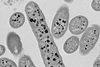

Ancient bacteria

This study grew out of an unexpected place. The Szöllősi group usually studies deep evolutionary history spanning up to billions of years. In a recent Science study, the group charted the earliest evolution of oxygen-breathing bacteria by predicting whether ancient bacteria possessed the genes necessary for aerobic metabolism.

When Fistarol joined the unit for a lab rotation, she suggested applying the same approach but at much smaller timescales – and with this, the team has now laid the foundation for creating new tools to address AMR.

Fistarol summarizes: “Our work points towards more robust and scalable genomic prediction. It’s a step closer toward faster, more cost-effective, and pragmatic resistance testing and monitoring.”

No comments yet