The ‘paradox of sex’ refers to the puzzle of why the sexual mode of reproduction is more common among living beings than the asexual mode. Sexual reproduction requires at least two mates, exposes individuals to a higher risk of diseases, and is more energy intensive.

In contrast, asexual reproduction makes up for all of these disadvantages by requiring only one parent while allowing for the rapid generation of offspring. Now, this ‘paradox’ has been bolstered by findings from a new study regarding a species of pathogenic fungi that infects a variety of cultivates grains, such as rice, wheat, barley, and finger millet.

Pyricularia (Magnaporthe) oryzae, a species of pathogenic filamentous fungi, wreaks havoc on global rice production as it causes the rice blast disease, which has earned it the moniker ‘rice blast fungus’.

Infection cycle

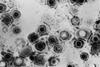

The infection cycle begins with asexual reproduction, where asexual spores called ‘conidia’ attach to the surface of the leaves of the rice plant. This produces an infection-specific structure called an appressorium, which starts to penetrate the outermost cell layer of the leaf, resulting in visible lesions on the leaf surface.

When conditions are favourable, specialized structures called conidiophores emerge and produce more conidia, which disperse through the wind or atmospheric droplets to more rice plants.

While this asexual mode of reproduction is the main driving force of the P. oryzae life cycle, scientists have demonstrated the successful sexual reproduction of this fungus in laboratory settings.

The fungus appears to have strains equivalent to biological males and biological females. However, most specimens collected from the fields show a loss of female fertility. The underlying genes and mechanisms responsible for the loss of sexual reproduction in P. oryzae have remained a mystery.

Paradox of sex

Researchers from the Tokyo University of Science, the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization, and the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Japan, have recently uncovered evidence for this advantageous loss of sexual reproduction in the rice blast fungus.

The research team was led by Professor Takashi Kamakura and Junior Associate Professor Takayuki Arazoe, from the Department of Applied Biological Science at the Tokyo University of Science. Their study is published in the journal iScience.

Regarding the premise of the study Prof. Kamakura explains: “Many fungal species have abandoned sexual reproduction, which doesn’t align with the evolutionary advantages of sex and fuels the paradox of sex. In the future, this research will also help breed useful industrial strains or understand how pathogens respond to mutations by explaining how diversity is acquired in fungi.”

Linking genes to sterility

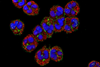

The researchers used multiple genetic experiments to identify which genes were linked to female sterility. Parental strains from P. oryzae field isolates were bred to give rise to female-sterile and female-fertile P. oryzae offspring.

Further genetic analyses revealed that mutations that resulted in dysfunctional Pro1 protein (involved in the expression of mating-related genes in filamentous fungi) caused female sterility in rice blast fungus.

Dr. Arazoe says: “To our surprise, the dysfunctional Pro1 increased the release of conidia but did not affect P. oryzae’s pathogenicity. We also found Pro1 mutations in wheat-infecting isolates, which is feared to spread worldwide (pandemic)—a finding that suggests a similar evolution (loss of sexual reproduction) has occurred in wheat blast fungus.”

Female sterility

Building on these results, the research group is already spearheading the identification and characterization of other genes that cause female sterility in fungal species.

Explaining the broader implications of this work, Prof. Kamakura concludes: “We’ve provided the first evidence that the loss of female fertility may be an adaptive advantage for this plant pathogen. The release of asexual conidia favors dispersal in the wild. This work also opens doors to study how diversity, another important aspect of fitness, is acquired in asexual breeders.”

No comments yet