New research by a team at Pennsylvania State University suggests that microbes in the human gut could be harnessed to block absorption of toxic metals like mercury and help the body absorb useful nutritional ones, like iron.

The group presented their findings at ASM Microbe 2023, the annual meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

Methylmercury, a neurotoxin, is particularly worrisome, said Daniela Betancurt-Anzola, a graduate student at Penn State who led the new study. It has a variety of toxic effects, and it is detrimental for neurological development during pregnancy and childhood, particularly in communities heavily reliant on fish-based diets.

Most methylmercury exposure is through fish or shellfish, but it can show up elsewhere as well. “It accumulates in living things, in plants and fish,” she said. “We eat those things, and it accumulates in us.”

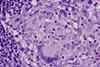

Gut bacteria

Betancurt-Anzola and her colleagues first analyzed thousands of genomes from gut bacteria, focusing on genetic determinants associated with the ability to interact with metals. Many genes are known to be connected to metal resistance, she said, but the group focused on those that enable bacteria to convert dangerous mercury to less toxic forms and absorb the heavy metal.

To understand how those genes function and impact the host, the team used metagenomic sequencing to study how human and mouse microbes responded to mercury exposure. Finally, the investigators used those insights to develop a probiotic specifically designed to detoxify a harmful type of mercury often found in the human diet. They inserted genes from Bacillus megaterium bacteria, which is known to be highly resistant to methylmercury, into strains of Lacticaseibacillus, a genus of lactic acid bacteria.

Perfect probiotic

“It’s a perfect probiotic for this because we have previously shown it works in humans, and now we are engineering it to make it even better,” Betancurt-Anzola said. “It is inside the gut, it grabs the methylmercury, then it goes out.”

For now, she said, the group is focused on understanding how gut microbes interact with mercury, but they plan to investigate other metals as well. Their ultimate goal is to develop interventions that could help reduce levels of dangerous metals — like mercury — and boost absorption of those that the human body needs.

“We are interested in studying how the entire microbial community reacts to different metals,” Betancurt-Anzola said.

No comments yet