In collaboration with scientists from the University of Würzburg, a research team from the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology studied the ambrosia fungus of the ship-timber beetle and made an astonishing discovery: this fungus stores significantly more nutrients than other types of fungi. These include mainly sugars and amino acids, as well as fatty acids, phosphorus, and nitrogen.

The beetle’s symbiotic fungus also accumulates various phenolic substances from the wood in its mycelium and produces monoterpene alcohols, which inhibit the growth of many other fungi. Interestingly, it releases acetic acid, which inhibits the growth of many fungi but has no effect on the ambrosia fungus itself.

READ MORE: Stinkbug leg organ contains symbiotic fungi to shield eggs from parasitic wasps

READ MORE: Beewolves protect symbiont microbes from toxic gas release

The ship-timber beetle (Elateroides dermestoides) is a species of ambrosia beetle. Unlike many of its relatives, which are social insects that live in colonies, it is solitary and does not live with other members of its species.

While ambrosia beetles usually have generation times of less than a year, the next generation of ship-timber beetles does not hatch for up to two years. It is also one of the largest European ambrosia beetles, reaching lengths of up to 18 millimetres.

Despite its solitary lifestyle, the ship-timber beetle does not live alone; it lives in a symbiotic relationship with the ambrosia fungus Alloascoidea hylecoeti, which provides it with nutrients.

First evidence of nutrient symbiosis with the ambrosia fungus

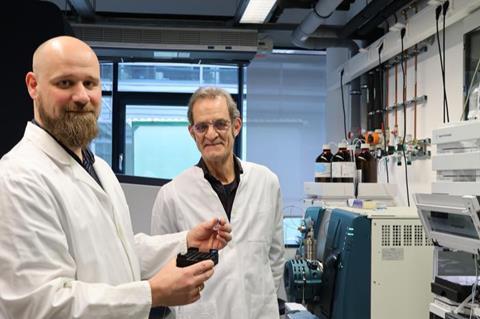

The team led by Maximilian Lehenberger from the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Jena investigated this beetle-fungus symbiosis in more detail. To achieve this, the researchers first analyzed the nutrients accumulated by the fungus in its mycelium — the network of thread-like structures that make up its vegetative body.

”Until now, it was only assumed that ambrosia fungi were nutrient-rich. However, there was hardly any useful data to support this. In our study, we were able to demonstrate for the first time that Alloascoidea hylecoeti, in particular, is extremely nutrient-rich. This fungus accumulates many nutrients — significantly more than other fungi, both symbiotic and non-symbiotic — including sugars, amino acids, ergosterol, fatty acids, and the essential elements phosphorus and nitrogen,” says Maximilian Lehenberger, head of the Forest Pathogen Chemical Ecology (FoPaC) project group in the Department of Biochemistry. This probably also explains why the ship-timber beetle can live in nutrient-poor wood for so long and grow so large.

Surviving in a highly competitive environment

The larvae of the ship-timber beetle spend a relatively long time living in the wood of recently deceased trees. This environment is challenging for the offspring of the beetles, which can grow up to two centimeters long, because dead wood is very poor in nutrients and teeming with competition.

In social ambrosia beetle systems, individuals can support each other by keeping harmful fungi at bay. This is not the case with solitary beetles.

The research team therefore hypothesized that the symbiotic fungus has developed its own strategies to protect itself from competing species. They found that the fungal symbiont Alloascoidea hylecoeti uses various phenolic substances obtained from the surrounding wood. The fungus accumulates these substances to such an extent in its environment that it inhibits the growth of many other fungi. It uses its ability to grow into wood to access further resources.

“Unlike many other fungi, the symbiotic fungus is neither broken down nor inhibited by plant defense compounds. Furthermore, it produces many substances that inhibit other fungi,” explains Maximilian Lehenberger.

A fungus that lowers the pH

The scientists were particularly surprised by the production of acetic acid, which they detected in fungal cultures and samples from beetle nests using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis. Experiments with fungal cultures revealed that the ambrosia fungus outcompetes other fungi by ‘acidifying’ its environment and lowering the pH to as low as 3.5.

Remarkably, Alloascoidea hylecoeti not only copes with a very high concentration of acetic acid, but actually thrives at a pH level that is extremely low for fungi.

“To date, acetic acid has not been detected in any other ambrosia beetle system. Since we were also able to identify acetic acid in the nests, this is clear evidence that it must play a role in nature too. The fungus utilizes not only acetic acid, but also a variety of other substances to inhibit competing fungi. These include monoterpenes such as linalool, terpineol and citronellol,’ says Jonathan Gershenzon, Head of the Department of Biochemistry. Citronellol is responsible for the lemon-like smell of this fungus.

Next steps

The impact of a highly acidic habitat on the larvae of the ship-timber beetle is unclear, as is the effect of the defensive substances that accumulate in the fungal biomass of their food source. Could this make them less attractive to predators? Could symbiotic bacteria in the beetles’ guts help break down high concentrations of phenolic compounds? The research team plans to address these questions and others in future experiments.

Topics

- Alloascoidea hylecoeti

- ambrosia fungus

- Ecology & Evolution

- Elateroides dermestoides

- Environmental Microbiology

- Fungi

- Healthy Land

- Jonathan Gershenzon

- Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology

- Maximilian Lehenberger

- Research News

- ship-timber beetle

- symbiosis

- UK & Rest of Europe

- University of Würzburg

- Veterinary Medicine & Zoonoses

No comments yet