An old antibiotic may provide much-needed protection against multi-drug resistant bacterial infections, according to a new study by James Kirby of Harvard Medical School, US, and colleagues. The finding may offer a new way to fight difficult-to-treat and potentially lethal infections.

Nourseothricin is a natural product made by a soil fungus, which contains multiple forms of a complex molecule called streptothricin. Its discovery in the 1940s generated high hopes for it as a powerful agent against Gram-negative bacteria, which, due to their thick outer protective layer, are especially hard to kill with other antibiotics.

But nourseothricin proved toxic to kidneys, and its development was dropped. However, the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections has spurred the search for new antibiotics, leading Kirby and colleagues to take another look at nourseothricin, as outlined in PLOS Biology.

Incomplete purification

Early studies of nourseothricin suffered from incomplete purification of the streptothricins. More recent work has shown that the multiple forms have different toxicities with one, streptothricin-F, significantly less toxic, while remaining highly active against contemporary multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Here, the authors characterized the antibacterial action, renal toxicity, and mechanism of action of highly purified forms of two different streptothricins, D and F. The D form was more powerful than the F form against drug-resistant Enterobacterales and other bacterial species, but caused renal toxicity at a lower dose. Both were highly selective for Gram-negative bacteria.

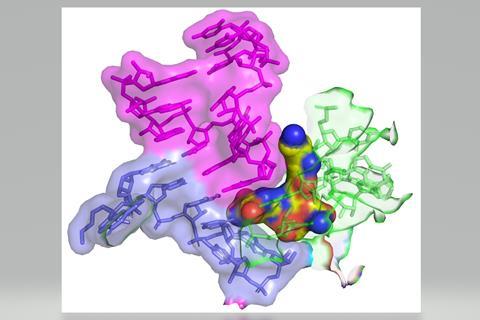

Using cryo-electron microscopy, the authors showed that streptothricin-F bound extensively to a subunit of the bacterial ribosome, accounting for the translation errors these antibiotics are known to induce in their target bacteria. Interestingly, the binding interaction is distinct from other known inhibitors of translation, suggesting it may find use when those agents are not effective.

“Based on unique, promising activity, we believe the streptothricin scaffold deserves further pre-clinical exploration as a potential therapeutic for the treatment of multidrug-resistant, Gram-negative pathogens,” Kirby said.

“Isolated in 1942, streptothricin was the first antibiotic discovered with potent gram-negative activity. We find that not only is it activity potent, but that it is highly active to the hardiest contemporary multidrug-resistant pathogens and works by a unique mechanism to inhibition protein synthesis.”

No comments yet