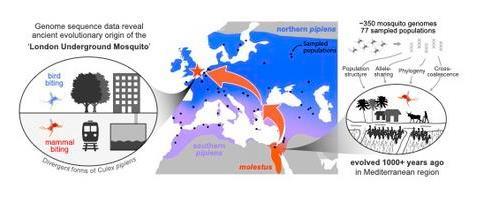

Evolutionary biologists have long believed that the human-biting mosquito, Culex pipiens form molestus, evolved from the bird-biting form, Culex pipiens form pipiens, in subways and cellars in northern Europe over the past 200 years. It’s been held up as an example of a species’ ability to rapidly adapt to new environments and urbanization.

Now, a new study led by Princeton University researchers disproves that theory, tracing the origins of the molestus mosquito to more than 1,000 years ago in the Mediterranean or Middle East. The paper publishes October 23 in the journal Science.

READ MORE: Mediterranean bacteria may harbor new mosquito solution

READ MORE: West Nile virus emergence and spread in Europe linked to agricultural activities

“This enigmatic mosquito became famous during WWII in London and seemed so perfectly adapted to living underground that people thought it must have evolved there. It became a textbook example of rapid evolution in modern cities. But cracks in this story have long been present and our analysis of DNA sequences from hundreds of mosquitoes supports a very different history,” said Lindy McBride, Associate Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Neuroscience at Princeton, and senior author on the new study.

Thousands of samples

McBride and former graduate student Yuki Haba, who is the first author on the study, worked with about 150 organizations from around the world to collect 12,000 samples of the two mosquito forms that represented both geographic and genetic diversity. Haba personally extracted and analyzed the DNA from 800 of them.

“Our analyses strongly suggest that molestus first evolved to bite and live alongside humans in an early agricultural society 1,000-10,000 years ago, most likely in Ancient Egypt,” said Haba who is now a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University.

One benefit of McBride’s expertise is that she is both a mosquito biologist and an evolutionary biologist, not one nor the other. In addition to revising one of the ‘textbook examples’ of urban evolution and adaptation, the work carries important public health implications.

“Our work provided new insight into how this mosquito varies genetically from place to place — insight that we think will help us better understand the role this species plays in transmitting West Nile virus from birds to humans,” said McBride.

Bird virus

West Nile virus is a bird virus that can be spread to humans when a mosquito first bites an infected bird and then bites a human. This type of virus ‘spillover’ to humans is most likely when mosquitos like to bite both types of hosts.

Mosquito biologists think that the flow of genes from human-biting molestus into bird-biting pipiens through hybridization creates such indiscriminate biters and has led to increased transmission of the virus to humans over the past two decades. Studying both forms of the mosquito and their evolution allowed the researchers to better understand when and where hybridization occurs.

McBride, Haba, and their collaborators found that hybridization is much less common than previously thought. But it does occur, especially in large cities, suggesting urbanization may promote genetic mixture of the two forms. The working hypothesis is that people in big cities could be at more risk for West Nile virus because of these hybrid pipiens mosquitoes that are willing to bite both birds and humans. But the researchers say that gene flow and biting behavior need to be studied further, with more sampling in urban and rural areas to draw conclusions.

“Our work opens the door to incisive investigation of the potential links between urbanization, hybridization, and spillover of the virus from birds to humans,” said Haba.

No comments yet