In the future, your clothes might come from vats of living microbes. Reporting in the Cell Press journal Trends in Biotechnology on November 12, researchers demonstrate that bacteria can both create fabric and dye it in every color of the rainbow—all in one pot. The approach offers a sustainable alternative to the chemical-heavy practices used in today’s textile industry.

“The industry relies on petroleum-based synthetic fibers and chemicals for dyeing, which include carcinogens, heavy metals, and endocrine disruptors,” says senior author and biochemical engineer San Yup Lee of the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. “These processes generate lots of greenhouse gas, degrade water quality, and contaminate the soil, so we want to find a better solution.”

READ MORE: Harnessing Microbial Power to Create Eco-Friendly Fabric Dyes

READ MORE: Coveted lac pigment may have a fungal origin

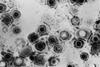

Known as bacterial cellulose, fibrous networks produced by microbes during fermentation have emerged as a potential alternative to petroleum-based fibers such as polyester and nylon.

Vivid pigment

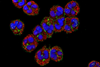

Taking this method a step further, Lee’s team set out to create fibers with vivid natural pigment by growing cellulose-spinning bacteria alongside color-producing microbes. The microbial colors stemmed from two molecular families: violaceins—which range from green to purple—and carotenoids, which span from red to yellow.

“At first, it completely failed,” says Lee. “Either the cellulose production was much less than expected, or it never got colored.” The team learned that the cellulose-spinning bacteria Komagataeibacter xylinus and the color-producing bacteria Escherichia coli interfered with each other’s growth.

Tweaking their recipe, the researchers found a way to make peace between the microbes. For the cool-toned violaceins, they developed a delayed co-culture approach by adding in the color-producing bacteria after the cellulose bacteria had already begun growing, allowing each to do its job without thwarting the other. For the warm-toned carotenoids, the team devised a sequential culture method, where the cellulose is first harvested and purified, then soaked in the pigment-producing cultures. Together, the two strategies yielded a vibrant palette of bacterial cellulose sheets in purple, navy, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red.

Everyday life

To see if the colors could survive the rigors of daily life, the team tested the materials by washing, bleaching, and heating them, as well as soaking them in acid and alkali. Most held their hues, and the violacein-based textile even outperformed synthetic dye in washing tests.

“Our work is not going to change the entire textile industry right now,” says Lee. “But at least we have proposed an environmentally friendly direction toward sustainable textile dyeing while producing cellulose at the same time,” says Lee.

The bacteria-based fabrics are at least five years from store shelves, Lee estimates. Scaling up production and competing with low-cost petroleum products are among the remaining hurdles. Real progress will also require a shift in the consumer mindset toward prioritizing sustainability over price.

“It’s our duty as humans to make the world a better place and allow our children to live happier lives,” says Lee. “This research is one of those efforts. Let’s be kind to the environment and do something good for future generations.”

No comments yet