Before plants evolved, vegetative life consisted of primitive green algae living in the sea. Like plants, these algae survived by performing photosynthesis, turning sunlight into energy. However, little light reaches the ocean where algae live; therefore, they evolved specialized organs to grab what little is available.

Among these tiny ocean algae are prasinophytes, which are among the earliest photosynthetic life forms on Earth. Like all photosynthetic organisms, they rely on a pigment–protein complex called LHC to capture sunlight. How efficiently LHC performs photosynthesis in different environments depends on the pigments bound to it.

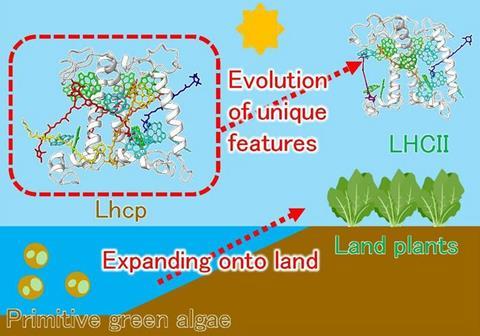

A research team including Associate Professor Ritsuko Fujii of the Graduate School of Science at Osaka Metropolitan University used cryo-electron microscopy to look at the three-dimensional structure and function of Lhcp, a unique prasinophyte LHC, from the microscopic alga Ostreococcus tauri. The team compared their results to LHCII, which is found in terrestrial plants.

Protein scaffold

They found that the basic design of the protein scaffold was similar, but there were structural differences in pigment binding and protein loops that affect how Lhcp absorbs light and transfers energy. Unlike the plant’s light-harvesting complex, Lhcp’s trimer architecture is stabilized by both pigment–pigment and pigment–protein interactions, especially involving a unique carotenoid arranged at the interface between subunits.

“The carotenoid stabilizes the structure and improves the efficiency of light adsorption of blue-green light, which is abundant in the deep-sea environment,” Professor Fujii explained.

Key changes

Their results showed that Lhcp includes structures unique to the algae despite sharing some structural and functional features with LHCII. These similarities and differences may be key changes that enabled plants to leave the oceans and colonize the land.

READ MORE: Marine algae use unique pigment to shield photosynthesis from excess light

“Understanding this molecular foundation can be used to uncover why, when, and how land plants selected LHCII over Lhcp during their evolutionary process,” Professor Fujii added. “This may be key to understanding this important evolution event.”

No comments yet