H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza poses a serious threat to both animal and human health. Since 2021, a novel H5N1 virus has caused thousands of outbreaks among poultry and wild birds across multiple countries.

In March 2024, H5N1 virus was first reported in dairy cattle in the United States. As of June 2025, outbreaks have been reported on more than 1,070 dairy farms across 17 states, with a mortality rate of up to 10% in affected cattle. Moreover, 41 dairy farm workers were infected by the virus, highlighting a significant threat to the global dairy industry and public health.

The H5N1 virus causes severe lesions in the mammary glands and contaminates milk, with H5N1 viral genes detected in 25% of retail milk samples in the U.S.

READ MORE: Claudin-11 plays a pivotal role in the clathrin-mediated endocytosis of influenza A virus

READ MORE: Killing H5N1 in waste milk — an alternative to pasteurization

However, as a typical respiratory pathogen, how does the H5N1 virus enter the mammary glands of dairy cows? A Chinese research team led by Professor Hualan Chen has solved this mystery, and they also provide a strategy on how to control the disease in cattle.

Lactating cows

The scientists performed this study by using a total of 50 cattle, including 46 lactating cows and four calves, in the animal biosafety level 3+ (P3+) facility at the Harbin Veterinary Research Institute.

They extensively investigated the replication, tissue tropism, and pathogenicity of H5N1 virus in cattle after different route inoculation, and they found that virus delivered into the nose can only replicate in tissues of the mouth and respiratory tract of the cattle, and virus inoculated into the mammary gland replicates only in the inoculated gland but does not migrate to neighboring mammary glands of the cattle, suggesting that entry through the teat is the only natural way the virus can infect the mammary glands of cattle.

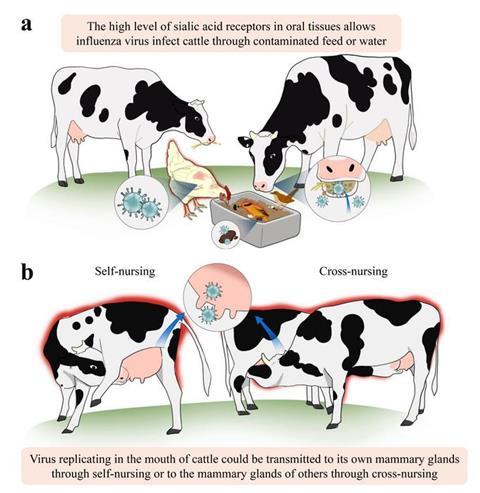

Given that some lactating cows’ “steal milk” through self-nursing or mutual-nursing, they speculated that “mouth-to-teat” transmission may be the route by which the H5N1 virus initially infects the mammary glands of dairy cows. They found that bovine oral tissues express high levels of sialic acid receptors, which favors viral infection through contaminated feed and water, and explains why the H5N1 virus could replicate efficiently in the oral cavity and be released for several days. They further demonstrated that H5N1 virus in the oral cavity of calves could be successfully transmitted to the mammary glands of the lactating cows they sucked.

Vaccine protection

Vaccination has been a strategy for control of highly pathogenic avian influenza in poultry in China and several other countries, but it is unknown whether vaccination also prevents H5N1 influenza infection in cattle. They tested two vaccines in lactating cattle, and demonstrated that both H5 inactivated vaccine and hemagglutinin-based DNA vaccine conferred complete protection against H5N1 infection in cattle, even after a high-dose of virus challenge via direct intramammary gland inoculation.

“This study not only provides crucial insights into controlling the ongoing cattle H5N1 influenza in the United States, but also offers scientific suggestions on how to prevent the H5N1 influenza outbreak in dairy cattle in other countries,” said Hualan Chen, a renowned virologist and the leader of this study.

No comments yet