Bacteria that thrive on Earth may not make it in the alien lands of Mars. A potential deterrent is perchlorate, a toxic chlorine-containing chemical discovered in Martian soil during various space missions.

Researchers at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) recently investigated how bacteria that can mould Martian soil into brick-like structures fare in the presence of this chemical. They find that although perchlorate slows down bacterial growth, it also surprisingly leads to the formation of stronger bricks.

“Mars is an alien environment,” says Aloke Kumar, Associate Professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and corresponding author of the study published in PLOS One. “What is going to be the effect of this new alien environment on Earth organisms is a very, very important scientific question that we have to answer.

READ MORE: Bacteria deployed to fix cracks in space bricks

In previous studies, the researchers used the soil bacterium Sporosarcina pasteurii to build “space bricks” from lunar or Martian soil that can potentially be used to set up extraterrestrial habitats. When added to synthetic Martian or lunar soil along with urea and calcium, the bacterium produces calcium carbonate crystals (precipitates), which help glue the soil particles together into bricks, in a process called biocementation. The process also requires the natural adhesive guar gum, a powdery polymer extracted from guar beans.

In the current study, the authors used a more robust, native strain of the bacterium that they discovered in the soils of Bengaluru.

Stressed cells

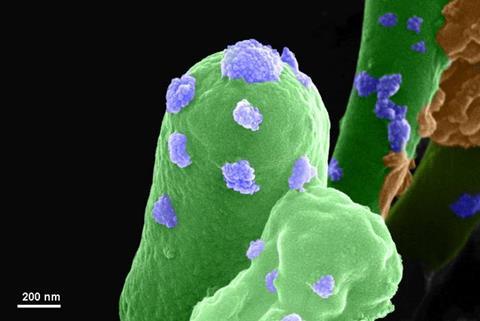

After first establishing its precipitate-forming skills, the researchers were curious to see if this strain can survive in the presence of perchlorate, which can be found at levels of up to 1% in Martian soils. In collaboration with Punyasloke Bhadury, Professor at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Kolkata, the team found that the bacterial cells become stressed in its presence – they grow slowly, become more circular in shape, and start clumping together into multicellular-like structures.

The stressed bacterial cells also release more proteins and molecules in the form of extracellular matrix (ECM) into the environment. Using electron microscopy, the researchers found that more calcium chloride-like precipitates were formed, and that the ECM formed little “microbridges” between the bacterial cells and the precipitates.

Effects on biocementation

Synthetic Martian soils do not usually contain perchlorate because it is flammable, but to test its effects on biocementation, the researchers carefully added the chemical to the soil simulant in the lab. To their surprise, they found that the presence of perchlorate made the bacteria better at gluing the soil together, but only if guar gum – essential for bacterial survival – and the catalyst nickel chloride are also present.

“When the effect of perchlorate on just the bacteria is studied in isolation, it is a stressful factor,” says Swati Dubey, currently a PhD student at the University of Florida and first author of the study. “But in the bricks, with the right ingredients in the mixture, perchlorate is helping.”

Dubey thinks that the ECM microbridges could be enhancing the bacteria’s biocementation skills by funneling nutrients to the stressed cells – a theory that the team wants to explore in future studies. They also want to test the isolate’s biocementation abilities in a more Mars-like high CO2 atmosphere, which they plan to simulate in the lab.

Landing missions

Ultimately, the team’s goal is to deploy this method as an alternative, sustainable building strategy, to rely less on carbon-intensive cement-based processes – both on Earth and Mars. Such technologies can also help make future Mars landing missions smoother – by helping build better roads, launch pads, and rover landing sites, says co-author Shubhanshu Shukla, ISRO astronaut who is pursuing his Master’s degree with Kumar at IISc. The uneven topography of the moon’s surface, for instance, has caused some landers to topple over, he adds.

“The idea is to do in situ resource utilisation as much as possible,” Shukla says. “We don’t have to carry anything from here; in situ, we can use those resources and make those structures, which will make it a lot easier to navigate and do sustained missions over a period of time.”

No comments yet