Researchers from the University of Florida Emerging Pathogens Institute and Texas A&M University have discovered local kissing bugs are harboring the parasite that can lead to Chagas disease, demonstrating that this rare, chronic disease — which is spread by blood-sucking kissing bugs — has a secure foothold in the U.S. and warrants more preventative measures.

The 10-year-long study, published July 7 in the Public Library of Science Neglected Tropical Diseases, was based on more than 300 kissing bugs collected from 23 counties across Florida. More than a third of the bugs were found in people’s homes, and the parasite that causes Chagas disease, Trypanosoma cruzi, was found in 30% of the tested bugs, with infections detected in 12 of the 23 counties.

READ MORE: Scientists tackle the rising global challenge of Chagas Disease

READ MORE: Innovative test diagnoses chagas disease in newborns

“We’ve done the groundwork to show that we have a vector in our state that is harboring a parasite, invading homes and feeding on humans and our pets,” said EPI member Norman L. Beatty, M.D. Since 2015, Beatty, the study’s co-first author, has dedicated his research program to the study of Chagas disease, which can attack the heart, brain and other organs with devastating results.

Silent killer

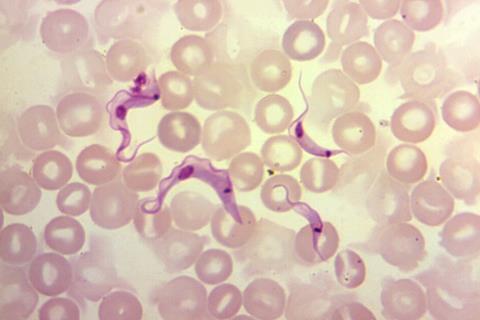

Kissing bugs, also known as triatomines, spread the T. cruzi parasite when their victims absorb or accidentally eat the bugs’ infected feces. The disease earned its reputation as a silent killer because it can be latent in the body for decades before showing severe symptoms. Chagas disease is considered rare in the U.S., but it is not closely tracked by most states.

To determine whether Chagas disease could be transmitted in Florida, the study collected insects that live in and around human dwellings. The researchers analyzed their stomach contents to determine the source of their last meal and whether the parasite was present.

They discovered that most kissing bugs found in the home had been feeding on humans, contrary to those discovered outside the home, which primarily contained blood from expected sources like mammals, as well as unexpected sources like amphibians and reptiles. This suggests that kissing bugs readily enter the home to bite humans, proving a crucial need for preventative measures to safeguard residences from Chagas disease.

Wood pile danger

Prevention requires inspecting the home for entry points and removing the bugs’ favored nesting sites, much like how mosquito prevention focuses on eliminating sources of standing water. Instead of standing water, the researchers aim to associate kissing bugs with wood piles, the insect’s version of home-sweet-home.

“Don’t keep those wood piles right next to your house. Don’t keep them right next to where your dog sleeps, I think that’s a huge part of it,” said EPI member Samantha Wisely, Ph.D. “That’s the integrated part, not just using pesticides and insecticides. … Habitat management, as well as changing your behavior.”

The bugs’ movement into homes comes as their natural habitat is disturbed by people moving into previously undeveloped land.

“We’re building into the Trypanosoma cruzi habitat, and so I think it increases the likelihood of people and companion animals becoming infected,” said Wisely, a professor at the UF College of Agricultural and Life Sciences.

Donated insects

Of the insects gathered, almost half were donated by community scientists and submitted to UF researchers and the Texas A&M Kissing Bug Community Science Program. This program, run by the Hamer Laboratory at Texas A&M, has been collecting community-donated insects since 2013, while Beatty and his team began their program in 2020.

The researchers, including Chanakya R. Bhosale, co-first author and undergraduate researcher from the UF/IFAS Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, described this community involvement as invaluable to expediting and broadening research. This approach not only epitomizes One Health science and the collaborative spirit of the EPI, but also speaks to the importance of multidisciplinary science.

“Well, you can’t do the study without it, for sure. So, it is — I’m going to try and think of the most important adjective I can — critical, pivotal. It is absolutely essential to doing this kind of work,” said associate professor at the UF/IFAS Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory Nathan Burkett-Cadena, Ph.D.

Disease risk

Moving forward, the team hopes this study can bring awareness to the present risk of Chagas disease transmission in Florida. Screening for Chagas is as simple as testing for a tick-borne disease. With this new information, clinicians and primary care providers can now add Chagas diagnostics to their arsenal against neglected tropical diseases in the Sunshine State.

“When I transitioned from [the] University of Arizona to start my faculty position at UF College of Medicine, my objective was clear to me: create a multidisciplinary, collaborative team, and dive into Chagas taking a One Health approach,” said Beatty, who is currently an associate professor.

“This project is only the beginning to our investigation into Chagas here in Florida. Our multidisciplinary approach to tackling a neglected tropical disease really bodes to the culture of ‘team science’ we promote here at UF.”

Topics

- Chagas disease

- Chanakya R. Bhosale

- Early Career Research

- Emerging Threats & Epidemiology

- Healthy Land

- Infection Prevention & Control

- Infectious Disease

- kissing bugs

- Nathan Burkett-Cadena

- Norman L. Beatty

- Parasites

- Research News

- Samantha Wisely

- Texas A&M University

- Trypanosoma cruzi

- University of Arizona

- University of Florida

- USA & Canada

- Veterinary Medicine & Zoonoses

No comments yet