University of Calgary researchers have discovered how Leishmania parasites hide within the body to cause Leishmaniasis.

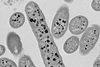

The tiny parasites are carried by infected sand flies. One to two million people in more than 90 countries are infected every year, with effects ranging from disfiguring skin ulcers to enlarged spleen and liver and even death.

This chronic disease has been difficult to detect in the early stages. Scientists realized that the parasite was somehow manipulating immune cells but this process had not been well understood.

“This is the first study that shows how the parasite stalls the process of regular neutrophil cell death which prevents the immune system from being activated,” says Dr. Nathan Peters, PhD, associate professor, at the Cumming School of Medicine (CSM) and principal investigator.

Accessing neutrophils

Neutrophils are a type of white blood cell which are the body’s first line of defense against infection and disease. Researchers in the Peters lab found that the parasite targets a receptor on the surface of the neutrophil to gain access inside the cell. Once there the parasite resists the neutrophils’ pathogen-killing molecules.

“The neutrophil then acts like a little Trojan Horse,” says Peters. “The parasite finds a niche inside these neutrophils and makes the neutrophil look like it is a regular dying cell, a process that happens constantly and therefore doesn’t activate the immune system.”

The parasite stalls the process of cell death in the neutrophil, enabling the parasite to persist inside the immune cell and establish infection. Experimental vaccines aimed at preventing the infection haven’t been effective.

Resisting vaccination

“The parasite’s behaviour interferes with our ability to vaccinate, because the immune system isn’t even aware that the parasite is there,” Peters says.

This research, conducted in mice, took place in a highly specialized laboratory, called the Insectary. This space within the Peters’ lab enables researchers to raise sand flies infected with the Leishmania parasite.

“Understanding the earliest interactions between the parasite and the host helps explain why previous vaccination strategies against Leishmaniasis have been unsuccessful,” says Adam Ranson, first author. “Our findings will contribute to bringing researchers closer to developing an effective vaccine against Leishmania infection.”

The study was highlighted as a ‘Top Read’ in The Journal of Immunology.

No comments yet