Just like every other creature, bacteria have evolved creative ways of getting around. Sometimes this is easy, like swimming in open water, but navigating more confined spaces poses different challenges.

Nevertheless, new research from the University of Chicago shows that a diverse group of bacteria has learned how to use the same basic movements to move through a wide range of environments no matter how complex, from unconstrained fluids to densely packed soil and tissues.

Some of the most common bacteria, like Salmonella and E. coli, move their flagella to propel themselves forward and rotate in space. The most well-studied movement pattern for this kind of bacteria is called “run-and-tumble,” where they swim forward (“run”) in one direction and then stop and rotate to reorient themselves in a new direction (“tumble”). This works great in unconstrained space, but in more confined spaces, their movement patterns look very different.

READ MORE: Arrangement of bacteria in biofilms affects their sensitivity to antibiotics

READ MORE: New research uncovers mechanics behind the skillful movement of shelled amoeba

“Very few bacteria move through just plain liquid without any obstacles. Bacteria live in soil. They colonize our gut and have to move through biological tissues and mucus,” said Jasmine Nirody, PhD, Assistant Professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy at the University of Chicago and senior author of the new study, which was published in the journal PRX Life. “We’ve been studying this very prevalent ‘run-and-tumble’ mode of motility for years, but in a very artificial environment. What happens when we introduce things that bacteria would encounter in the real world?”

‘Run-and-tumble’ vs ‘hop-and-trap’

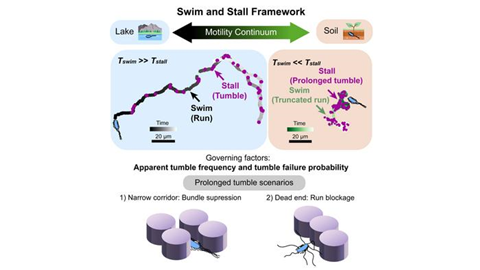

In 2019, researchers from Princeton studying E. coli moving through dense hydrogels identified a new movement pattern they called “hop-and-trap,” where bacteria get trapped in place by an obstacle before they can reorient themselves and hop through an opening. But in the real world, there might be quite a bit of variation between the two experimental extremes of completely open water and dense hydrogels. Nirody and her team wanted to understand if this hop-and-trap behavior was really something new, or a variation of the familiar run-and-tumble method.

To test this, the team built a microfluidic device where they could track E. coli bacteria moving through environments of different complexity. Microfluidics are a system of silicon wafer chips, usually used to monitor the flow of tiny amounts of fluid. For their experiments, Nirody’s team developed chips with pillars to build a maze of obstacles for bacteria. The pillars were spaced at varying distances and randomness to simulate complex, real-world environments like soil.

Swim-and-stall

In open spaces, the bacteria moved around as expected with the usual run-and-tumble motion. In more confined spaces with more pillars, the length of their runs was shortened when they ran into a pillar. The amount of time they spent tumbling was longer when they got trapped and had to reorient themselves to escape. The researchers called this “swim-and-stall,” but while it looks very different to the naked eye, they realized this was essentially the same run-and-tumble movement pattern, but with different results in the more complex environments.

The team also performed mathematical simulations of bacteria executing the same run-and-tumble behavior in unconfined environments as in environments that were confined, and the simulation results matched the behavior they saw in the experiments exactly.

“It’s doing the same basic thing. It’s not changing the rate that it tumbles or even changing the length of time that it’s running. It’s just failing to succeed,” Nirody said.

Like walking through mud

The difference is like watching a person walk through the mud, which at first glance looks very different from walking on dry land. It takes longer to drag their legs forward; they might swing their arms wider or twist and turn to wrench themselves free. But it’s essentially the same movement pattern: putting one foot in front of the other.

“It might look really different, but the underlying behavior is the same,” Nirody said. “By doing these experiments, we showed that the bacteria are not actually doing something different. They are executing the exact same program across environments.”

From an evolution standpoint, reusing the same program for movement makes a lot of sense. Developing a completely different way of getting around through open vs tight spaces, or anything in between, would be incredibly complicated and costly for simple organism like bacteria. Instead, they landed on a method that works well enough, most of the time.

Baseline is cheaper

“If they have to use a different genetic program that changes how often they tumble in a different environment, or if they constantly have sense and respond every time it changes, that can be very costly. But if they develop a baseline that works pretty well across all the environments, that’s just much cheaper to do,” Nirody said. “And that’s exactly what we found. Bacteria that live in environments where they’re constantly facing these changes picked a thing that is just good enough for everything, rather than optimizing.”

The study, “Bacterial Motility Patterns Vary Smoothly with Spatial Confinement and Disorder,” was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Simons Foundation, the James S. McDonnell Foundation, and the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure. Additional authors include Haibei Zhang and Edwin M. Munro from UChicago; Miles T. Wetherington from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Cornell University; Hungtang Ko from Princeton Univeristy; and Cody E. FitzGerald, Leone V. Luzzatto, and István A. Kovács from Northwestern University.

No comments yet