A new study reveals that the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein can spread from infected to uninfected cells, triggering an immune response that mistakenly targets healthy cells.

The research identifies how this viral protein binds to cell surfaces and shows that enoxaparin, a common anticoagulant, can block this harmful interaction, pointing to a potential avenue for treatment. These findings shed light on the mechanisms behind severe COVID-19 complications and immune-driven tissue damage.

READ MORE: The role of understudied dysfunctional immune cells in severe COVID-19: new research

READ MORE: Study uncovers how Covid-19 is so good at defeating the innate immune response

A new study involving collaborative efforts of the laboratories of Dr. Alexander Rouvinski, Prof. Ora Schueler-Furman and Prof. Reuven Wiener, led by PhD students Jamal Fahoum and Maria Billan from the Faculty of Medicine at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, uncovers a surprising mechanism by which the SARS-CoV-2 virus, responsible for COVID-19, might cause immune-mediated tissue damage by targeting cells it has never infected.

A fruitful collaboration with clinicians: Dr. Dan Padawer, Prof Dana Wolf and Dr. Orly Zelig and their team members from several departments at Hebrew University - Hadassah Medical Center provided the complementary clinical data necessary for this work. SARS-CoV-2 infection experiments essential for this research were performed in the recently established high biocontainment national laboratory, Barry Skolnick Biosafety Level 3 (BSL3) National Unit at the Core Research Facility at the Faculty of Medicine of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Nucleocapsid protein

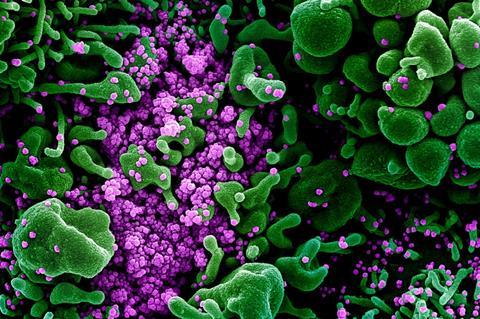

Published in Cell Reports, the study demonstrates that the virus’s nucleocapsid protein (NP), best known for its role in packaging viral RNA inside infected cells, is transferred to neighboring uninfected epithelial cells and attach to their surfaces. Once present on these otherwise healthy cells, NP is recognized by the immune system and is targeted by anti-NP antibodies, which mistakenly label the cells for destruction. This process activates the classical complement pathway, leading to inflammation and cellular damage that might contribute to severe COVID-19 outcomes and complications such as long COVID.

This research uncovers a surprising way in which the SARS-CoV-2 virus can misdirect the immune system, causing the attack of healthy cells, simply because they have been marked by a viral protein. Understanding this mechanism opens the door to new strategies for preventing immune-driven damage in COVID-19 and possibly other viral infections, which are a subject of the ongoing studies in the laboratories leading this research.

The researchers used laboratory grown cells, sophisticated imaging techniques, and samples from COVID-19 patients to understand how a specific viral protein, called the nucleocapsid protein attaches to healthy cells. They discovered that this protein sticks to certain sugar-like molecules found on the surface of many cells, called Heparan Sulfate proteoglycans. When this happens, clumps of the viral protein form on these healthy cells. The immune system then mistakenly attacks these clumps using antibodies, which sets off a chain reaction that might damage the cells, both infected and healthy cells in the infected organism.

Blood thinner

The researchers also found that the drug enoxaparin, a commonly used blood thinner, can block the viral protein from sticking to healthy cells. It does this by taking over the spots the protein would normally bind to, being a heparin analog. In both lab experiments and when samples obtained from patients were tested in the lab, enoxaparin stopped the protein from attaching to cells and helped prevent the immune system from mistakenly attacking them.

The authors dedicate the article to the memory of the late Prof. Hervé (Hillel) Bercovier, a gifted microbiologist, an inspiring scientist, and a great mentor. This research was supported by several research funds, including major contributions from The Edmond and Benjamin de Rothschild Foundation and The Israel Science Foundation of the Israel Academy of Science and Humanities.

No comments yet