A new mathematical model uses wastewater samples to effectively forecast the number of clinical COVID-19 cases in a community five days in advance.

The approach was developed and validated by Hokkaido University environmental engineer Masaaki Kitajima and colleagues in Japan. It could help healthcare authorities better tailor infection control policies, especially when clinical surveillance is lacking. The researchers reported their findings in the journal Environment International.

Testing wastewater samples for SARS-CoV-2 as a means to predict surges in clinical cases has been attracting attention. Scientists have been researching this approach since the beginning of the pandemic. However, current methods aren’t particularly sensitive and can only detect increasing cases without being able to forecast their numbers within a community.

Rainy days

Kitajima and his colleagues had already developed a method to detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater samples. But this method requires solid material and does not work well with diluted wastewater on rainy days or with treated wastewater that has been clarified and is mostly liquid.

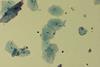

So, instead of using low-speed centrifugation to create pellets from wastewater samples that then go on to be tested, they used special filters that can capture the viral RNA from diluted wastewater. This is followed by extracting RNA from the filter, amplifying it, and then running polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests to detect it. They call the new method Efficient and Practical Virus Identification System with Enhanced Sensitivity for Membrane (EPISENS-M).

They used EPISENS-M to test weekly samples taken from two wastewater treatment plants in Sapporo, Japan over the course of two years, from May 2020 to June 2022. They compared the SARS-CoV-2 data they obtained from these samples with clinical surveillance data of COVID-19 cases in the two catchment areas.

“EPISENS-M was able to detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater with more than 50% accuracy when new cases were still less than one in every 100,000 residents,” says Kitajima.

Early shedding

Further analyses of the data showed that infected people start shedding the virus into the sewage system around five days before they were reported through clinical testing.

The researchers used the wastewater virus data together with clinical surveillance data to develop a mathematical model that takes the fluctuations of viral shedding along the course of disease into consideration to successfully predict the number of new cases expected to occur over the subsequent five days.

“We still need to understand how vaccinations, for example, affect viral shedding from infected individuals into the sewage system,” says Kitajima.

“Our approach also involves expensive equipment. So further research is still needed to improve this method and to make it more cost-effective. Still, this research highlights the potential of wastewater-based epidemiology to forecast the number of clinical cases in a community even when fully notifiable clinical surveillance is not practised.”

No comments yet