Zika virus is a single-stranded RNA virus and a member of the family Flaviviridae. The virus was first described in 1947 in Rhesus macaque monkeys in Uganda and later described as causing human disease in 1952.

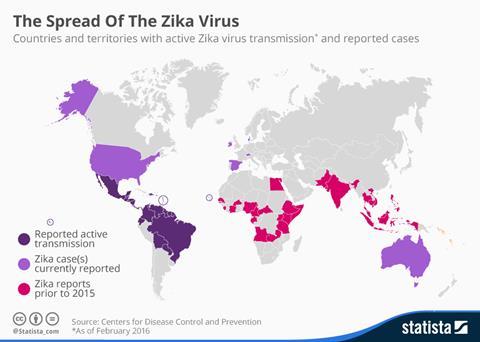

Initially providing sporadic outbreaks across regions of Africa, the virus gained media traction after its emergence in South American populations around 2015. However, it has been recorded in Africa, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific since 2007. During this time, the World Health Organisation declared the virus a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) due to the congenital malformations presented in newborns (such as microcephaly) and its ability to cause Guillain–Barré syndrome in adults. The most recent reported cases of the virus were in India in 2021. However, underreporting cases increased amid the global pandemic as societal attention was towards COVID-19 rather than Zika, leading to concerns of the disease being silently transmitted through populations. There are no specific treatments for the Zika virus as symptoms are usually mild and self-limiting, such as a fever and joint pain.

On 26 April 2023, the United Kingdom embarked on the first clinical trial of a Zika vaccine in humans. The trial began at the University of Liverpool at the Clinical Research Facility within the Royal Liverpool University Hospital. The vaccine originates from a 2016 Zika Rapid Response grant awarded to Dr Tom Blanchard (Consultant at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital and Honorary Senior Lecturer at the University of Liverpool) in collaboration with colleagues in his former position at the University of Manchester and researchers at UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). Despite the challenge of COVID-19 appearing during this research, the vaccine project made headway in understanding immunity towards the virus and how to apply this to develop a suitable vaccine. This vaccine could unlock the potential to curb the spread of the Zika virus, particularly from mother to foetus, who are at the highest risk from infection due to congenital malformations, stillbirths and miscarriages.

The initial vaccine was produced in 2016 in response to the rapid spread of the Zika Virus through the Americas. By the end of 2016, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) estimated that there were over half a million cases of suspected Zika virus. Since then, the vaccine has been enhanced for improved efficacy and ability to scale up the vaccine production in industry, moving away from a laboratory concept to a viable vaccine fit for human use. This has led to the Phase 1 human clinical trial being initiated with up to 40 healthy volunteers between 18 and 59 being recruited and work carried out over the next nine months.

To date, several clinical and non-clinical studies have been undertaken by scientists worldwide, including cell and animal models and human trials; however, we have yet to complete a successful human trial for a vaccine for Zika, which has taken the vaccine through to pharmaceutical production. In 2017 a $110 million vaccine trial was established as part of the response to the 2016 PHEIC. However, some unlikely challenges were faced during the trial. After the initial outbreak in 2015, the number of cases rapidly plummeted in the following year to just a few thousand suspected cases reported. This made it difficult to assess the efficacy signal of the vaccine as it would be unlikely to catch the disease. In addition, large cohort populations had already been infected with the Zika virus after its previous outbreak, limiting the number of individuals eligible to participate in this large-scale trial in specific geographical locations.

One possibility researchers have pondered has been to perform human challenge models, whereby healthy participants would be intentionally infected with the virus to assess vaccine utility. Human challenge models raise ethical concerns. However, reduced transmission of Zika in populations has made it harder to study new vaccines as part of phase III clinical efficacy trials, a requirement for drugs to go from laboratory benches onto pharmaceutical shelves.

Whilst no countries are currently experiencing active outbreaks, this disease has not disappeared. Countries residing along the equator still experience a number of cases each year. Furthermore, as temperatures increase due to global warming, there is the risk of the Zika vector, the Aedes mosquito spreading further from its current geographical boundaries to North America and Europe. We see a global decline in reported cases, however, there is no doubt that the virus can bounce back. To be prepared for potential future outbreaks, a vaccine must be developed to ensure successful distribution in locations where the Zika virus is a public health concern at present and in the future.

No comments yet