“In our study, we focused on Candida albicans and the importance of its toxin Candidalysin. The fungus is a natural part of the human microbiome and coexists with numerous other microorganisms such as bacteria in our gastrointestinal tract,” says Richard Bennett, Professor at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, USA.

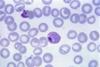

C. albicans multiplies in two different growth forms: a round yeast form and an elongated hyphae form.

“Previous studies in mice indicated that the yeast form is advantageous for colonization of the intestine,” says Bernhard Hube. He leads a department at the Leibniz-HKI and is professor at the Friedrich Schiller University Jena.

“The fungus develops its pathogenic effect primarily in the hyphal form. This form secretes Candidalysin and thus damages host cells,” explains Hube.

“If C. albicans exists primarily as a colonizer of the intestine, i.e. as a round yeast form, why are almost all isolates of the fungus able to form hyphae?” asked Bennett and Hube. “What selection pressure ensures that the fungi do not lose the ability to form hyphae?”

Complex bacterial community

Comparative studies on mice with a complete microbiome and a microbiome reduced by antibiotics now show that the previous assumption that the yeast form is better suited for colonization needs to be revised. As soon as a complex bacterial community is present, C. albicans uses both the yeast and the hyphae forms to colonize the intestine efficiently. But why is the hyphae form advantageous when bacteria are present?

“Only in the hyphal form does the fungus produce the toxin Candidalysin, which has an antibacterial effect. This enables the hyphae form to compete with bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract. The toxin inhibits the metabolism and thus the multiplication of the bacteria. This gives the fungus a competitive advantage. The release of Candidalysin associated with the formation of hyphae therefore probably contributes to the fact that the fungus is such a successful colonizer of humans. This may explain why the hyphal form of C. albicans is also so important during colonization of the intestine,” says Hube. If the formation of hyphae is blocked, the fungus is also less able to colonize the intestine.

“The fungus has therefore not developed the toxin primarily to damage human cells, but to be able to compete with bacteria on mucous membranes,” says Hube, summarizing the key message of the study. The researchers want to investigate the interaction between fungi and bacteria and their effects on the host in more detail. “The Cluster of Excellence ‘Balance of the Microverse’ at Friedrich Schiller University Jena, with its focus on microbial interactions, offers us an ideal environment for this,” says Hube.

No comments yet