Wheat production is threatened by a major fungal disease: yellow rust. Researchers at the University of Zurich have found traditional wheat varieties from Asia that harbor several resistance-conferring genes. They may serve as a durable source of yellow rust resistance in commercial varieties in the future, highlighting the importance of genetic diversity for food security.

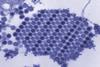

Yellow rust, also known as stripe rust, is caused by a fungal pathogen named Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. The plant disease affects around 88% of global bread wheat production and is one of the most devastating threats to wheat yields. New strategies against the fungus are therefore urgently needed.

READ MORE: A blueprint for making cereal crops more resistant to fungal disease

READ MORE: New discovery boosts wheat’s fight against devastating disease

An international team headed by researchers at the University of Zurich (UZH) has now discovered two genomic regions in traditional wheat varieties from Asia which confer resistance to the disease.

“If such genes can be transferred to commercial wheat varieties, they could be important in combating yellow rust,” says Kentaro Shimizu, professor at the UZH Department of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies, who is responsible for a new study on the subject.

Genetic diversity of wheat local varieties

For decades, targeted breeding of wheat focused on developing high-yielding varieties. While these modern varieties helped feed the world, their limited genetic diversity led to increased vulnerability to threats such as pests, diseases and extreme climates.

In contrast to modern varieties, traditional wheat varieties have been maintained by local farmers in different regions of the world and therefore less impacted by the loss of genetic diversity. Traditional varieties from Asia appeared particularly promising, for they have been underexplored despite being a potential reservoir of genetic diversity with higher disease resistance.

During her PhD in Shimizu’s team, Katharina Jung conducted the research on wheat yellow rust resistance in collaboration with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in Mexico and the Kyoto University in Japan. Jung screened both traditional and modern varieties from Japan, China, Nepal and Pakistan.

First, she identified yellow rust resistant wheat plants in large-scale field experiments in Reckenholz, Switzerland, and at CIMMYT, Mexico. Then, she located genomic regions that contribute to yellow rust resistance, so-called quantitative trait loci.

Targeted search for novel yellow rust resistances

Jung uncovered two potentially new genomic regions related to yellow rust resistance: One is specific to a traditional variety from Nepal, while the other is more broadly distributed across traditional varieties from Nepal, Pakistan, and China in the southern Himalayan area.

“Interestingly, the southern Himalayan area is believed to be the origin of the yellow rust pathogen itself. Taken together with our findings, we hypothesize that traditional varieties from this area might harbor unique and stable resistances to yellow rust,” says Jung. A more targeted search for novel yellow rust resistances from this area could potentially provide long-lasting protection against a wide range of pathogen strains.

Safeguarding local varieties and farming practices

The new results underscore the importance of conserving genetic diversity and traditional varieties in wheat to combat diseases and other threats. Farmers have cultivated and maintained these traditional varieties in different parts of the world for generations, which is of great value for future food security.

“Traditional varieties must be preserved both in gene banks and in farmers’ fields before they are lost forever. Their use and benefit-sharing should be done in close collaboration with local communities, as their knowledge and practice have paved the way to the genetic diversity we observe today,” says Jung.

The wheat varieties provided by Kyoto University were essential for this project.

“I cannot emphasize enough how valuable such a collaboration is in making scientific progress,” says Kentaro Shimizu. The UZH Global Funding Scheme, managed by the Global Affairs office, supported this project. Collaborations between UZH and Kyoto University have existed for many years. In 2020, the alliance between two institutions was converted into a Strategic Partnership.

No comments yet