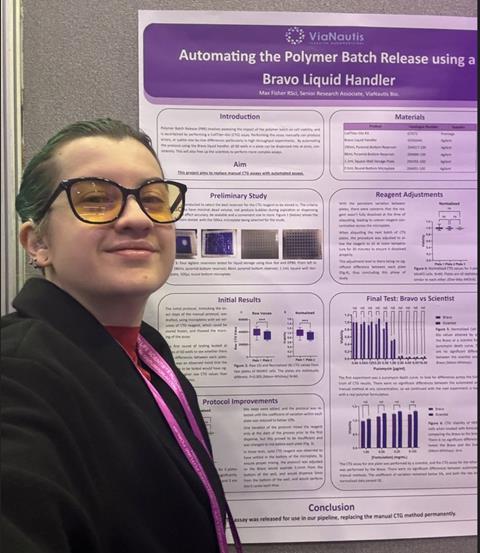

Max Fisher, a leading Disability & LGBTQIA+ Advocate, and Senior Research Associate at ViaNautis Bio, has been named as individual winner of the Dorothy Jones Diversity & Inclusion Achievement Award 2025.

The prize is part of the Applied Microbiology International Horizon Awards 2025, which celebrate the brightest minds in the field and promote the research, group, projects, products and individuals who continue to help shape the future of applied microbiology.

The Dorothy Jones Diversity and Inclusion Achievement Award honours Dorothy Jones’ commitment to promoting diversity and inclusion within STEM. This award aligns with the UN Sustainable Development Goals which recognise that reduced inequalities are a core factor in attaining peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future. This sits alongside strategies for achieving gender equality, eliminating disparities in education outcomes, ensuring equal access to education for all, and strengthening the global scientific workforce.

This award acknowledges individuals that have made significant strides in these areas. It celebrates initiatives that dismantle barriers to participation and representation, especially for underrepresented groups, and recognises inclusive research and experimental design and practice.

Activist and advocate

Max Fisher is an activist and an advocate for disability and LGBTQIA+ rights, in particular, advocating for the inclusion of disabled and queer people in STEM. In 2024, they were named the UK’s most influential disabled scientist at the Disability Power 100.

“I speak openly about intersectionality in the workplace, drawing on my lived experiences as a queer, DeafBlind, and disabled scientist. I am passionate about being a role model for future scientists and others from marginalised backgrounds who are pursuing careers in science,” Mx Fisher said.

READ MORE: Winners of Applied Microbiology International Horizon Awards 2025 announced

Max says they originally became a scientist because of their disability.

“For as long as I can remember, I have lived with chronic pain, alongside other symptoms,” they said.“Doctors didn’t seem to know what was wrong, because as it turns out, I was living with a rare disease called Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, which is currently untreatable. Because of this lived experience, I wanted to be a part of a team that would eventually create drugs for diseases without cures. I decided to pursue a career in pharmacology.

“When I was 17 I was a part of a scheme that allowed me to conduct a pharmacological research project within a hospital in order to give me a taste of what my future could look like. And I loved it.”

Journey to pharmacology

Their journey took them to Nottingham Trent University to study Pharmacology for their undergraduate degree (BSc (hons)), followed by a Masters by Research (MRes), also in Pharmacology.

“During my time at university, my disabilities became more apparent and I started using a wheelchair,” Max said.“I got involved with my student union as their elected Equality and Diversity Officer for Gender. I was able to run a series of intersectional campaigns around trans inclusion and disability awareness alongside my studies.

“My undergraduate thesis looked at the performance of vital enzymes within the body, which, respectfully, showed me what kinds of science I wasn’t interested in. While interesting, I struggled with the biochemistry side of things, and couldn’t picture myself doing that sort of work long-term.

“But I was struggling to picture myself being a scientist at all. In the media, there were no images of scientists using wheelchairs, or walking aids, or even scientists with dyed hair.”

Immunology and inflammation

But their masters’ thesis was much more up their street: “It looked at immunology, inflammation, and respiratory diseases, and I got to culture my first cell line. I learned a lot of practical lab techniques, and really got stuck in to the basics of data analysis. But the question still remained. Was there actually a place in the world for a scientist like me?”

After graduating in 2018, Max was unemployed for three and a half years, applying for hundreds of jobs, and receiving hundreds of rejections.

“I was in receipt of universal credit, which required me to show evidence of job applications, and met with a job coach on a weekly basis. The question I was asked every week, without fail, was “Are you sure you can actually be a scientist?”. I was sure.

“Eventually, through my network, I received my first offer of employment to be a cell line engineer at a global biotech company.

“From day one, I bought my whole disabled self to work. I introduced myself via a site-wide email as our “newest deaf employee”, and gave some advice on how to best communicate with me. People loved it!”

Edited cell lines

In the lab, Max worked to grow edited cell lines for use in research.“I used robotic liquid handlers, as well as standard tissue culture methods to do this. Alongside the lab work, I was also selected to launch and co-lead our disability Employee Resource Group (ERG), which supported disabled employees in all aspects of their work, as well as their wellbeing,” they said.

“After 18 months, I moved on to my next role as a senior research associate at a small nanomedicine company. Here I still work hands-on with different cell lines every day, but I also get to expand my skills into assay and platform development, using techniques such as flow cytometry and microscopy. I have also continued being an advocate for queer and disabled people in STEM, and in the wider world. We belong in STEM, and we belong everywhere.”

The challenge of stigma

Stigma is a huge problem in the sector, Max said.“During my unemployment, CVs that contained my role as the Equality and Diversity Officer for Gender, or my participation in wheelchair basketball, were rejected.

“Meanwhile, towards the end, CVs that only contained my degree, and my name would often get me an interview. I was frequently told that I would never be a scientist and should give up and apply for reasonable jobs instead.

“Now, people often look puzzled when I tell them I’m a scientist, just based on how I look - whether that’s with my white cane, my hearing aids, or my green hair.

“This stigma doesn’t just apply to disability or queerness either. It applies to everything: race, age, gender, religion, culture, appearance, language… the list is endless, unfortunately. These people spend more time looking for reasons why you can’t really be a scientist, than supporting you to become the best scientist you can be.”

Dignity and respect for all

With over a decade of experience in EDI advocacy, Max has consistently championed dignity and respect for all. Professionally, they are a registered scientist (RSci) with The Science Council and a Member of the Royal Society of Biology (MRSB).

“I am incredibly proud to have been chosen as the individual winner for the Dorothy Jones Diversity and Inclusion Achievement Award. I am equally proud to have won this award alongside a team winner as well,” Max said.

“Diversity doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and it’s important that we celebrate diversity across a wide spectrum to showcase that the work we do belongs in STEM. Diversity and Inclusion in STEM is the future.”

Sign up to AMI’s newsletter to make sure you receive the latest news, including updates on the 2026 Horizon Awards.

No comments yet