Oregon Health & Science University researchers and partners are developing what could become the first-ever treatment against the debilitating joint pain that can last months or years after becoming infected with the emerging Chikungunya virus.

Although scientists have tried to create vaccines and treatments to fight the virus, none have been approved to date. Nearly $4.7 million in new National Institutes of Health funding is now helping OHSU scientist Daniel Streblow to advance an experimental Chikungunya antiviral drug he has been developing since 2015. The new research could lead the compound to be evaluated in humans for the first time by the end of 2027.

“We have the potential to develop an antiviral that could be used to treat millions of people during large Chikungunya outbreaks, and prevent long-term disease in people who are persistently affected by this debilitating disease,” said Streblow, a professor at OHSU’s Vaccine & Gene Therapy Institute.

Streblow is leading the new research project in collaboration with Mark T Heise, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Richard Whitley, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The research team also includes scientists at the University of Colorado Denver, Southern Research in Alabama and SRI Biosciences in California.

The mosquito species whose bites spread the virus live in warmer climates. Chikungunya virus was first identified in Africa in 1952, but can now also be found in Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Americas and Europe. Climate change could expand its geographic range. Globally, more than 360,000 Chikungunya cases and 77 deaths have been identified so far this year, with most cases occurring in Brazil, India and Guatemala. The virus began spreading in the United States in 2014; the spread was limited, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports there have been 13 locally acquired cases in US states since then.

An initial bout with Chikungunya can cause fever, joint and muscle pain, a rash and other symptoms for one to two weeks. Young children, older adults and those with high blood pressure or diabetes have a higher risk of experiencing severe disease or death. While most people fully recover, about 30 to 40% will experience persistent joint pain — known as chronic Chikungunya arthritis — for months or even years. The resulting pain can be so incapacitating that some are unable to work.

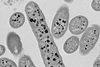

Similar to the COVID drug Paxlovid, the experimental Chikungunya antiviral compound is designed to reduce the total amount of virus, or viral load. Described as a 2-pyrimidone small molecule inhibitor, the compound — patent pending — works by binding to the viral RNA polymerase through which viruses normally replicate. Streblow describes the compound as “first in class,” because it targets a unique site on viral RNA polymerase and it hasn’t been used to treat humans before.

In previous, unpublished research involving mice, studies found the experimental antiviral reduced Chikungunya viral loads by up to 1,000 times, and stopped long-term joint symptoms when it was given one to two weeks after infection. And when the compound was given later, the research team also found that persistent viral loads, which are thought to cause long-term disease, were also reduced.

Now, the research team is working to tweak the antiviral compound’s chemistry and turn it into a pill that can be taken by mouth. The team plans to test the reformulated compound’s effectiveness and safety in more advanced animal models.

Next, the research team aims to submit an Investigational New Drug application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. If their application is approved, OHSU would lead a Phase 1 clinical trial to evaluate the experimental treatment’s safety and efficacy in people for the first time.

Topics

- Chikungunya virus

- Daniel Streblow

- Emerging Threats & Epidemiology

- Infection Prevention & Control

- Innovation News

- Mark T Heise

- mosquitoes

- One Health

- Oregon Health & Science University

- Richard Whitley

- Southern Research

- SRI Biosciences

- University of Alabama

- University of Colorado Denver

- University of North Carolina

- USA & Canada

- Virology

- Viruses

No comments yet