Orchids are more than just beautiful flowers. For centuries, they have captivated scientists—from Charles Darwin to his modern-day successors—with their spectacular role in the drama of evolution, forming exceptional interactions with pollinators in the light and mycorrhizal fungi in the dark.

To kickstart their lives, most if not all orchids are obligately dependent on their fungal partners for energy—a phase known as ‘initial mycoheterotrophy’. Some even maintain this fungal dependency, partially or fully, throughout their entire lives. Scientists have long suspected that an orchid’s shift in this nutritional strategy—from self-sufficient to fungus-dependent—is linked to a switch in its fungal partners.

READ MORE: Deadwood-decomposing fungi feed germinating orchids

READ MORE: Orchids support seedlings through ‘parental nurture’ via shared underground fungal networks

Back in 2021, Dr. Deyi Wang and collaborators confirmed this evolutionary correlation using a global dataset they assembled, which included mycorrhizal data from approximately 750 orchid species worldwide. Now, that same dataset has unlocked a deeper mystery: what truly governs the global patterns of these orchid-fungal relationships? While individual studies had pointed to factors like geography, climate, and the orchid’s own ecophysiology, their combined influence remained unknown on a worldwide scale.

The laws of orchids

In a new study published in Plant Diversity, Wang and her international collaborators provide the answer.

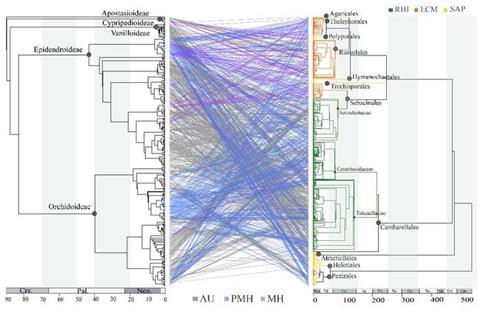

The team used a global dataset of orchid-fungal associations to study how mycorrhizal fungal communities vary in relation to orchid phylogeny, trophic mode, biogeographic distribution and broad niche variables. Their global meta-analysis leads to a general conclusion: an orchid’s fungal community is driven more strongly by its ecophysiology and biogeography than by its phylogeny.

Given that half of current orchid-fungal association data is unusable due to incomplete reporting, the researchers also emphasized the importance of standardized documentation of host information, fungal identity, and habitat characteristics.

No comments yet