Researchers have identified a protein that evolved concurrently with the emergence of cellular compartments crucial for the multiplication of the toxoplasmosis pathogen.

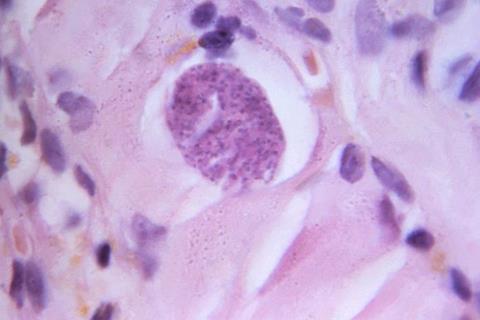

Toxoplasmosis is an infectious disease found worldwide, caused by the single-celled parasite Toxoplasma gondii. In humans, infection poses a particular risk to pregnant woman, as it can lead to birth defects. Like the closely related malaria pathogen –Plasmodium falciparum – and other related species, T. gondii possesses special organelles, so-called rhoptries and micronemes, for infecting the host cell.

A team led by Professor Markus Meissner, Chair of Experimental Parasitology at LMU, and Professor Joel Dacks from the University of Alberta (Canada) has now investigated the evolution of this infection machinery and identified an organelle-specific protein, which could become a promising target for new therapeutic approaches.

Protein machinery

In the course of their evolution, the parasites not only developed special organelles such as the rhoptries and micronemes, but also all the protein machinery required to ensure the production and functioning of the organelles. The so-called organelle paralogy hypothesis (OPH) proposes that the current diversity of cell organelles came about due to the duplication and subsequent diversification over evolutionary time of certain genes that code organelle identity. “In order to create their specific structures, the parasites had to repurpose some proteins and add others,” explains LMU parasitologist Elena Jimenez-Ruiz.

To investigate to what extent and in what manner the diversity of organelles emerged in the Apicomplexa – the group of organisms to which T. gondii and P. falciparum belong – the researchers combined comprehensive bioinformatic genetic analyses and molecular cell biology methods. In this way, the scientists were able to identify 18 candidate proteins that correlated with the emergence of new organelles and their protein machinery in apicomplexans.

“For one of these proteins, known as ArlX3, we were then able to demonstrate experimentally that it plays a key role in the formation of micronemes and rhoptries in T. gondii,” says Jimenez-Ruiz. “Without ArlX3, the parasites can no longer reproduce.”

Since ArlX3 occurs in the parasites but not in human cells, the researchers think the protein could represent a promising target structure for new therapeutic options. Moreover, their methods could potentially be used to identify further specific protein subgroups that could yield important insights into the cell biology of the parasites.

No comments yet