A new study from the Systems Immunology Research Group at the Institute of Biochemistry, HUN-REN Biological Research Centre, Szeged, reveals that our immune system does more than defend against viruses. In certain cases, it induces mutations within viruses that make them easier to recognize later on. The findings have been published in Nature Communications.

The research was led by Máté Manczinger and Gergő Balogh in collaboration with Csaba Pál and Balázs Papp. Experimental validation was coordinated by Gábor Szebeni.

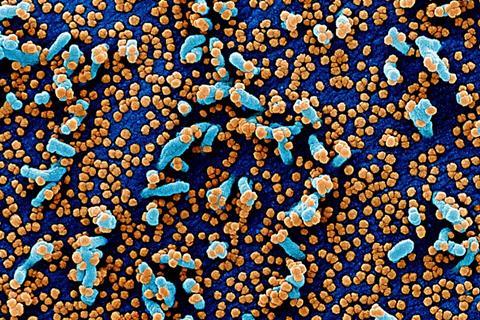

During the COVID-19 pandemic, an unprecedented amount of genetic data became available on the SARS-CoV-2 virus, allowing researchers to analyse in exceptional detail how the pathogen changed over time. The study shows that a substantial portion of mutations in the viral genome are not random errors or viral strategies, but are instead caused by the human body’s own APOBEC enzymes.

READ MORE: AI learns to ‘speak’ genetic ‘dialect’ for future SARS-CoV-2 mutation prediction

READ MORE: New technology uncovers mechanism affecting generation of new COVID variants

These enzymes are part of the early, non-specific immune response, and they can chemically modify the genetic material of viruses. According to the researchers, the mutations they introduce do not typically weaken immune recognition — in fact, they often enhance it. They generate changes in viral proteins that are more easily detected by HLA molecules, the immune system’s key antigen-presenting components that reveal hidden, infected cells to T-cells.

Covid protein variants

The team analysed thousands of SARS-CoV-2 protein variants and found that APOBEC-associated mutations lead to better HLA binding and stronger T-cell activation — ultimately improving the effectiveness of the immune response.

“This discovery sheds light on a previously unrecognized aspect of the interaction between our body and viruses: the immune system does not only react to pathogens but also exerts a form of genetically encoded pressure on them, which can make them more detectable in the long run,” said Gergő Balogh, first author of the study.

The phenomenon is not limited to the coronavirus: similar APOBEC-driven patterns have been observed in other viruses as well. As HLA types vary significantly among individuals, the findings may also open new avenues in personalized medicine.

The research could support future vaccine development, as APOBEC-induced mutations follow predictable patterns — meaning that immune-visible viral variants could potentially be anticipated even early in an outbreak, improving preparedness for emerging strains.

No comments yet