New laboratory research shows that when viruses attack a species that forms toxic algal blooms, those thick, blue-green slicks that choke waterways and that threaten ecosystems, drinking water, and public health, what results might be even worse than before the infection.

The finding questions the long-held theory among scientists that the viruses help regulate the negative effects of these blooms.

READ MORE: Study identifies viruses in red tide blooms for the first time

READ MORE: Study uncovers how the plastisphere can influence growth of harmful algal blooms

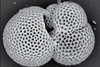

A team of environmental microbiologists led by Dr. Jozef Nissimov, a professor at the University of Waterloo, has shown for the first time experimentally that when viruses infect and kill Microcystis aeruginosa, a common species responsible for harmful algal blooms (HABs), they cause the release of high levels of the toxin microcystin-LR into the water from the infected cells.

Liver toxin

The microcystin-LR toxin, a known liver toxin, remained in the water at levels roughly 40 times higher than the recommended concentration for recreational waters for several days after the infected cells died, even when the water itself appeared clear. This finding is significant because water clarity is often a prime visual cue to trigger additional testing, which can ultimately determine the safety of water for drinking and recreational use.

“Our research shows us that the relationship between viruses and toxic algae is more complicated than we thought,” Nissimov said. “We need to better understand these interactions before we can consider viruses as something that acts as a natural HAB-control strategy.”

Harmful algal blooms

HABs are a global concern. Depending on the type of species responsible for a bloom, exposure may result in skin rashes, stomach upset, liver damage and neurological problems. Pets and livestock can also develop health issues from exposure to contaminated water. In Canada, microcystins are the only algal toxins with national guidelines for water used for drinking and recreational activities, making this discovery particularly urgent for regulators and decision-makers.

HABs can result in so-called dead zones, where oxygen in the water is depleted, posing a survival risk to fish and other aquatic organisms. Beyond these immediate effects, HABs often force the closure of beaches, fisheries, and nearshore recreational areas. In the Great Lakes, HABs caused by M. aeruginosa occur annually, with the most frequent and severe ones occurring in western Lake Erie.

The work opens the door to further studies, including investigating how climate change might influence the dynamics between viruses, algae, and toxin release. Temperature and nutrient pollution are key factors in making HABs more frequent and widespread globally. Another area for future exploration is how microcystin-LR and other HAB toxins get metabolised and reduced by other organisms in the environment, and how the virus infection that triggers their excess release from the infected cells can be countered.

Forecasting and mitigation

The researchers say their findings could support better forecasting and mitigation strategies for HABs, ultimately helping governments, municipalities, and water agencies make more informed, evidence-based decisions.

“Viruses likely still have a very important role to play in controlling harmful blooms, but we need to ask the right questions, starting with whether the benefits of viral infection in our bodies of water outweigh its potential detrimental effects,” Nissimov said.

The study, Virus Infection of a Freshwater Cyanobacterium Contributes Significantly to the Release of Toxins Through Cell Lysis, was recently published in Microorganisms.

No comments yet