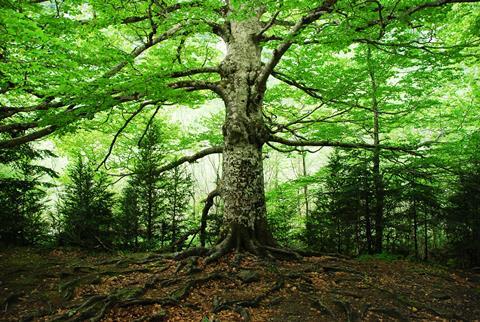

Feeding a growing population while rebuilding depleted soils is one of agriculture’s biggest challenges. Mycorrhizal fungi — especially arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) — work at the root zone, trading nutrients and water for plant-made sugars and helping crops stay strong when conditions aren’t ideal. When these fungal networks are thriving, they can improve nutrient uptake, support stronger root systems, and reduce the need for fuels to stretch as far, with their input. It’s a small-scale partnership with big implications for the future of farming.

The mechanism of mycorrhizal symbiosis

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi establish symbioses with plant roots through a coordinated exchange of chemical signals. Root exudates — including strigolactones and other signaling molecules — promote AMF spore germination and hyphal growth toward the root surface.

In parallel, AMF release signaling compounds that prime host root cells for accommodation, helping regulate early colonization events and supporting compatibility between partners. This pre-contact signaling phase is critical because it influences whether colonization proceeds efficiently and whether the association stabilizes over time.

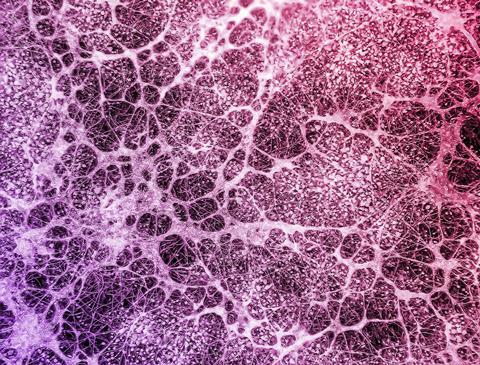

Following the entry into the root cortex, AMF form arbuscules, highly branched intracellular structures that function as the primary interface for bidirectional resource transfer. At this interface, the fungus supplies mineral nutrients pulled from the soil, with phosphorus often standing out because it diffuses poorly and is easily depleted around roots.

Depending on the soil and the AMF taxon involved, nitrogen and micronutrients can also move through this pathway. In return, the plant provides the fungus with carbon derived from photosynthesis. This exchange is closely regulated enough to keep supporting nutrient acquisition while maintaining a balanced cost-benefit relationship for both organisms.

AMF influences plant nutrition largely through the extraradical mycelium. This external hyphal network extends beyond the root depletion zone and explores soil volumes that roots alone cannot effectively access. This network increases the effective absorptive surface area and can improve uptake of poorly mobile nutrients, as well as water under moisture-limited conditions.

Beyond nutrient and water acquisition, extraradical hyphae contribute to soil aggregation and structure through physical enmeshment of particles and the production of extracellular compounds. As a result, AMF activity links to broader soil function and resilience in managed agricultural systems.

Agronomic benefits of AMF application

AMF is increasingly becoming the tool of choice for improving crop performance while supporting healthier soil function. In agronomic settings, their value is often measured through outcomes like nutrient-use efficiency, stress tolerance, and yield stability under variable field conditions.

Enhanced plant nutrition and water uptake

A key agronomic benefit of AMF is their ability to improve nutrient acquisition — particularly phosphorus (P), which moves slowly through soil. As roots absorb available phosphate, a localized P depletion zone forms, limiting further uptake.

AMF overcome this constraint by extending extraradical hyphae beyond the depletion zone to access phosphorus pools outside the immediate rhizosphere and transport them back to the plant. This mycorrhizal pathway complements root uptake and can be especially useful in low-phosphorus or reduced-input systems. AMF also contribute enzymatically by supporting the mineralization of organic phosphorus, further increasing P availability.

While AMF do not fix atmospheric nitrogen, they can play a substantial role in nitrogen nutrition. Research shows that mycorrhizal associations may supply over 50% of a plant’s nitrogen requirements under certain conditions, so fungal-mediated nutrient transfer is important.

In addition, AMF enhance the uptake of relatively immobile micronutrients such as zinc and copper, which are critical for enzymatic and physiological processes. The same hyphal networks that improve nutrient acquisition also increase water uptake by accessing soil microspores beyond the reach of roots, supporting plant performance during periods of limited moisture.

Improvement of soil health and structure

Beyond direct effects on plant nutrition, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi play a critical role in soil structure through their extensive hyphal networks. As hyphae grow through the soil matrix, they physically entangle mineral particles like sand and clay, binding microaggregates into larger, more stable macroaggregates. This aggregation increases pore connectivity, which improves water infiltration, gas exchange, and resistance to erosion.

AMF further reinforces soil structure through the production of glomalin-related soil protein. Glomalin acts as a persistent binding agent, coating soil particles and protecting aggregates from disintegration during heavy rainfall. Studies also suggest that glomalin contributes 4% to 5% to soil carbon pools in tropical forests.

However, before these biological processes can be fully restored, a thorough understanding of baseline soil conditions is necessary. Conducting soil and groundwater assessments is particularly important on land transitioning from long-term industrial or conventional agricultural use. Experts recommend these assessments because residual contaminants like heavy metals and pesticides may limit the effectiveness of AMF-based remediation and regeneration strategies.

Increased tolerance to abiotic stress

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are often linked to stronger crop performance when conditions are not ideal, especially during drought. In addition to helping plants access more water, AMF-colonized roots tend to support tighter control over stomata, which can reduce unnecessary water loss. Mycorrhizal plants also frequently have higher concentrations of compatible solutes, such as proline and soluble sugars. These compounds help cells hold on to water and keep basic metabolic processes running when soil moisture drops.

These benefits extend beyond drought, though. Under saline conditions, AMF associations commonly reduce the accumulation of sodium and chloride in aboveground tissues and improve potassium status, which helps plants maintain a more stable ionic balance.

In soils contaminated with heavy metals, AMF can also influence metal behavior in the root zone by binding ions to their fungal structure, thereby lowering the amount that reaches the shoots. Taken together, AMF functions as a buffer that can help plants remain productive across drought, salinity, and contamination.

Suppression of soil-borne pathogens

AMF can reduce disease through physical occupation and resource competition. As they colonize root tissue and develop an external hyphal network, they effectively claim space on and around the root surface, leaving fewer colonization sites for pathogenic fungi, oomycetes, and some plant-parasitic nematodes. Changes in rhizosphere chemistry reinforce this effect, as mycorrhizal plants often exhibit altered root exudation patterns and altered microbial recruitment.

In addition to direct competition, AMF contributes indirectly by improving host plant vigor and modulating defense readiness. Plants that are better supplied with water and nutrients are typically less susceptible to stress-related disease expression and can allocate more resources to endogenous defense processes.

AMF colonization is also associated with mycorrhiza-induced resistance, in which the plant’s immune system is primed rather than fully activated. Priming does not trigger a constant, high-cost defensive state. Instead, it prepares the plan to respond more rapidly and strongly when a pathogen challenges it. This enhanced responsiveness is often linked to defense signaling pathways involving hormones such as jasmonic acid and salicylic acid, along with increased capacity for producing protective secondary metabolites and cell wall defenses.

The drawbacks of conventional farming

Modern production systems are often optimized for short-term output. Still, many of the same practices can undermine soil biology, which contributes to the loss of 24 billion tons of fertile land every year worldwide.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are particularly sensitive to repeated disturbance. When their networks are disrupted, the soil can become more reliant on external inputs to maintain yields. Over time, this can contribute to a cycle in which biological nutrient cycling declines while chemical replacement becomes the dominant strategy.

Physical disruption through tillage

Intensive tillage mechanically breaks apart the extraradical mycelial networks that AMF build through the soil. When hyphae are repeatedly severed, the fungus loses continuity and has a reduced capacity to explore soil volumes, deliver nutrients, or contribute to aggregation. This also has structural consequences. Hyphal networks help bind soil particles into stable aggregates, so disrupting them can weaken stability, increase compaction risk, and accelerate erosion.

Chemical disruption via fungicides

Broad-spectrum fungicides suppress fungal growth, but they are not always selective for pathogens. In systems where fungicides are used routinely, non-target effects can reduce beneficial fungal abundance and diversity, including AMF populations.

When this occurs, colonization rates and functional benefits may decline, limiting the plant’s access to the mycorrhizal nutrient pathway and reducing resilience to stress. Repeated chemical pressure can also change soil microbial community structure in ways that further reduce symbiotic capacity.

Biological disruption through high fertilization

High inputs of soluble, readily available fertilizers can reduce the plant’s dependence on AMF. When phosphorus is abundant in the root zone, plants often allocate less carbon belowground, which limits the energy available to sustain mycorrhizal partners.

Over time, reduced carbon allocation can suppress colonization and diminish the density of fungal networks in the soil. This weakens biological nutrient acquisition pathways and increases the likelihood that productivity becomes dependent on continued synthetic input use rather than being supported by a stable soil microbial ecosystem.

How AMF is a cornerstone of regenerative agriculture

AMF are increasingly recognized as a foundational biological component of regenerative farming systems like no-till and cover cropping. These systems aim to rebuild soil health and function rather than focusing on short-term yields. By maintaining continuous plant cover and minimizing solid disturbance, these practices support more abundant and diverse AMF populations, enhancing nutrient cycling, soil structure, and microbial connectivity.

Meta-analyses of field studies indicate that AMF inoculation can significantly enhance crop productivity under natural conditions. For example, AMF treatment increased overall crop yields by 23% across 13 commonly grown crops in rainfed systems, along with increases in shoot and root biomass. In regenerative contexts where inputs are reduced, robust mycorrhizal networks help close nutrient loops, improve plant resilience, and strengthen soil ecology as part of a larger strategy to sustain productivity.

Advanced research and future directions

As interest in AMF grows, research is taking place to understand optimization and responsible deployment. Current work focuses on improving consistency in field performance while addressing genetic, molecular, and ethical considerations tied to large-scale agricultural use.

Commercial inoculants: challenges and quality control

One of the most active areas of applied research centers on the production and performance of commercial AMF inoculants. Because AMF are obligate symbionts, they cannot be cultured without a host plant, making large-scale production technically complex. Inconsistent species composition and differences in soil conditions can influence field outcomes. As a result, quality control and strain selection remain key challenges, especially across diverse cropping systems and soil types.

Genetic and molecular frontiers

At the molecular level, advances in genomics and transcriptomics are improving understanding of the genes involved in AMF colonization, nutrient exchange, and stress signaling. This research is helping identify why some crop varieties respond more strongly to mycorrhizal associations than others. Long term, these insights may inform breeding programs aimed at developing crop cultivars with enhanced compatibility with AMF, allowing plants to leverage symbiotic nutrient pathways under reduced input conditions more effectively.

An ethical consideration with sourcing biologicals

As demand for agricultural biologicals increases, questions around sourcing and environmental responsibility are becoming more prominent. AMF inoculants are often derived from natural ecosystems, raising concerns about overharvesting, biodiversity loss, and unintended ecological impacts. Ensuring that biological products are sourced sustainably, produced under controlled condition,s and free from contaminants is increasingly viewed as essential.

A clear example can be found in the sourcing of marine-derived antibiotics, where extraction from polluted waters has raised concerns about toxin bioaccumulation and unintended ecological and human health impacts. These risks highlight why careful sourcing, monitoring, and production standards are key — not only for performance, but for preventing biological inputs from becoming vectors for contamination rather than tools for regeneration.

The future of farming starts underground

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi demonstrate the potential already inherent in the soil when biological systems are supported. By strengthening nutrient uptake, improving soil structure, and helping crops tolerate stress, AMF can complement regenerative practices. At the same time, consistent field results still depend on sound management and high-quality inoculants. As research advances, AMF are likely to remain a key tool for improving productivity while rebuilding the long-term health of agricultural soils.

No comments yet