For decades, microbiology has leaned heavily on a familiar set of tools: Petri dishes, well plates, and flasks. These static culture systems have shaped how we study microbes, from identifying disease-causing bacteria to testing antibiotics and understanding basic microbial behaviour. They are popular because they are reliable, relatively simple to use, and excellent for isolating specific organisms. Traditional microbial culture remains one of the cornerstones of microbiological research and diagnostics. By allowing microbes to multiply in carefully chosen growth media under controlled lab conditions, researchers can determine what organisms are present, how many there are, and how they respond to treatments.

But as useful as these methods are, they also come with limitations. Most notably, they offer a very simplified snapshot of microbial life. In the real world – and especially inside the human body – microbes don’t live on flat agar surfaces or in still liquid. Instead, they experience constant movement, changing nutrient levels, mechanical forces, and interactions with surrounding tissues and other organisms. This mismatch between how microbes live and how we study them has led researchers to look for new experimental approaches that better reflect reality. Here is where microfluidics steps in.

Microfluidics is a fast-growing field focused on manipulating tiny volumes of fluid, often within channels no wider than a human hair. These systems, commonly called “chips”, are already widely used in bioengineering and cell biology. What makes them exciting for microbiology is the level of control they offer. Researchers can fine-tune fluid flow, generate stable gradients, and create microenvironments that closely resemble those found in places like the gut, lung, or bloodstream. Despite this potential, around 90% of microbial experiments are still carried out under static conditions. So, what are we missing by ignoring flow? And how can microfluidics help close the gap?

Why flow conditions matter

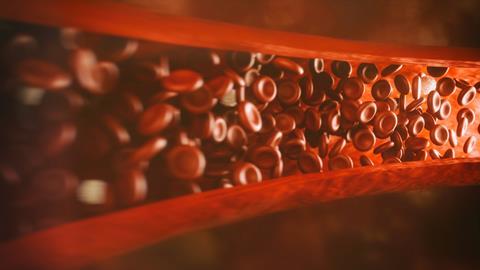

Inside the body, microbes are almost never sitting still. They are pushed and pulled by fluids, exposed to shear forces, and constantly adapting to changes in their surroundings. These physical cues influence everything from how microbes attach to surfaces to how they form biofilms, express genes, and interact with host cells or competing species. When we remove flow from the equation, we risk overlooking behaviours that are critical for understanding infections and microbial ecosystems.

Microfluidic systems make it possible to introduce controlled flow into experiments without sacrificing precision. Researchers can apply specific shear stresses that mimic intestinal peristalsis, airflow in the lungs, or blood circulation. This means microbes can be studied under conditions that are far closer to what they actually experience in the body, rather than how they behave on a Petri dish. Over time, this shift can lead to more realistic insights into microbial physiology and pathogenicity.

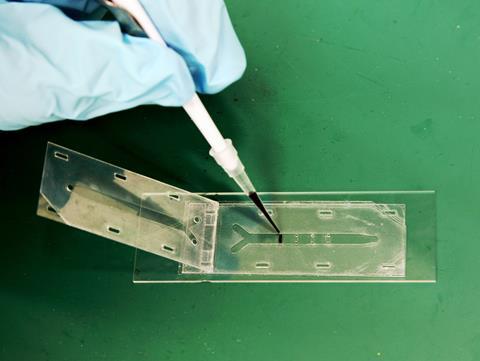

At a practical level, microfluidic devices work a bit like circuit boards for liquids. They are etched with networks of tiny channels that guide fluid movement in highly predictable ways. At this scale, fluids behave differently than they do in larger systems, allowing for stable, laminar flow and precise control. Syringe pumps are often used to drive flow, and their performance is judged by factors like flow stability and settling time – both of which are crucial for maintaining consistent experimental conditions.

Single-cell insight into complex microbial dynamics

One of the most powerful advantages of microfluidic flow systems is their ability to support single-cell-level observation. In traditional cultures, microbial behaviour is averaged across millions of cells, masking important differences. Microfluidic systems, by contrast, allow researchers to track single microbes over time while keeping their environment tightly controlled.

This single-cell perspective has transformed how scientists study processes like biofilm formation, revealing how individual cells attach, divide, and disperse under fluid. It’s also invaluable for studying co-cultures, where different species compete or cooperate in shared spaces. By physically organising microbes within microchannels, researchers can observe interactions such as quorum sensing, metabolic cross-feeding, or microbial warfare in real-time.

Better control without overcomplication

There is a common belief that microfluidics requires expensive automation and highly specialised equipment. While some systems do fall into that category, many are surprisingly accessible. Manually controlled setups can still deliver stable, reproducible flow and offer a good balance between flexibility and precision.

By reducing issues like evaporation, inconsistent media exchange, and handling variability, microfluidic platforms often improve reproducibility compared to static cultures. Flow rates, channel shapes, and environmental conditions are defined by design rather than technique, which helps reduce experimental noise and makes results easier to compare across experiments and labs.

Challenging the “microfluidics is too complicated” mindset

Despite its growing impact, microfluidics is often perceived as being inaccessible to many microbiology labs. It is commonly associated with clean rooms, complex fabrication processes, and expensive automation, leading some researchers to dismiss it as impractical or overly technical. While these concerns were once justified, the reality today is quite different.

Many modern microfluidic systems are designed to be modular and user-friendly, requiring little more than basic training to operate. Commercially available chips can be connected to simple syringe pumps and microscopes already present in most labs. In parallel, open-source designs and low-cost fabrication methods, such as soft lithography and 3D printing, have significantly lowered the barrier to entry. Researchers no longer need to be engineers to run flow-based experiments – collaboration and accessible tools have changed the landscape.

Another important shift is the growing emphasis on interdisciplinary research. Microbiologists are increasingly working alongside engineers, physicists, and data scientists, allowing expertise to be shared rather than duplicated. This collaborative approach makes it easier to adopt microfluidic techniques without requiring every lab to develop in-house technical mastery. Importantly, even relatively simple flow setups can offer major advantages over static cultures, meaning that meaningful improvements do not require highly complex systems.

Reframing microfluidics as a scalable tool rather than an all-or-nothing technology is key. Labs can start small, using a flow that answers specific biological questions, and build complexity only when necessary. By challenging the idea that microfluidics is inherently difficult or inaccessible, microbiology can begin to integrate flow-based thinking more widely and more confidently.

Real-world examples: what microfluidics is already changing in microbiology

While microfluidics may still feel new to many microbiologists, it is already reshaping how certain microbial behaviours are studied. One where this is especially clear is antibiotic testing. In traditional static cultures, bacteria are typically exposed to a fixed concentration of an antibiotic, and their response is measured over time. However, in the body, drug concentrations rise and fall, are transported by fluids, and form gradients across tissues. Microfluidic systems allow researchers to recreate these dynamic exposure profiles, revealing that some bacteria survive or adapt in ways that static assays fail to capture. In several studies, microbes that appeared susceptible under static conditions showed increased tolerance when grown under flow, helping to explain why some antibiotics perform well in the lab but poorly in patients.

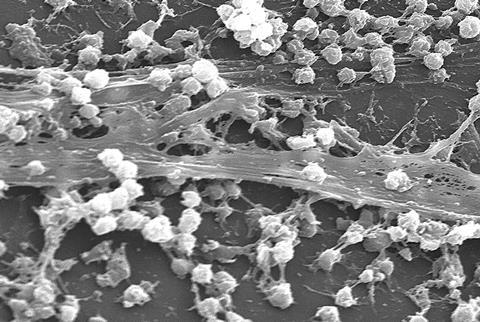

Biofilm research has also benefited enormously from flow-based systems. Biofilms that form under shear stress often look and behave very differently from those grown on still surfaces. Under flow, biofilms tend to develop more complex three-dimensional structures, altered gene expression, and increased resistance to antimicrobial treatments. Microfluidic devices allow researchers to observe biofilm formation from the very first attachment event through to maturation and dispersal, all while controlling flow rate and nutrient delivery. This has provided new insights into how biofilms persist on medical devices, in the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients, or within industrial pipelines.

Another rapidly growing application is the use of gut-on-a-chip models to study host-microbe interactions. These systems combine microbial cultures with human cells under conditions that mimic intestinal flow and mechanical motion. Studies using these platforms have shown that fluid movement alone can dramatically change which microbes successfully colonise the gut lining and how they interact with host cells. Certain species that struggle to persist in static cultures thrive under flow, while others are washed away. These findings highlight how physical forces, not just chemical signals, shape microbial ecosystems.

Together, these examples illustrate a key point: when flow is introduced into experimental design, microbial behaviour often changes in meaningful and sometimes unexpected ways. Microfluidics doesn’t just add technical complexity – it reveals biology that would otherwise remain hidden.

Linking microbiology to lab-on-a-chip technologies

Microfluidics also connects microbiology to a broader ecosystem of lab-on-a-chip research. These technologies are increasingly used in drug development, toxicology, and tissue modelling. For example, microfluidic systems that mimic how drug concentrations change over time have been shown to better predict in vivo outcomes than static assays. While not all of these studies focus on microbes, the principles apply directly to infections, antimicrobial testing, and host-microbe interactions.

Compartmentalised chips that allow fluidic communication between separate regions have also been used to model complex biological connections, such as interactions between different organs or tissues. Similar designs could be used to study polymicrobial infections or microbial communities interacting with host cells. Advances in organ-on-a-chip and 3D bioprinting further highlight how microfluidics is reshaping how we study living systems.

Opportunities, challenges, and the road ahead

Microfluidics isn’t here to replace traditional microbiology – and it doesn’t need to be. Instead, it offers a powerful complement, adding layers of realism and resolution that static systems can’t provide. That said, there are challenges. Designing flow-based experiments takes time, analysing high-resolution, time-lapse data can be demanding, and simplified microenvironments must still be interpreted carefully in a biological context.

Looking ahead, controlled flow systems are likely to play an increasing role in microbiology. As researchers aim for experiments that better reflect real-life conditions, microfluidics provides a practical way to bridge the gap between classic in vitro models and the complexity of living systems. For those studying biofilms, microbial interactions, or host-associated microbes, adding flow to experimental design isn’t just a technical upgrade – it’s a chance to ask better, more meaningful biological questions.

Written by Linda Vidova, Scientific Writer at Ossila

Linda is currently completing her PhD in cancer genetics. She is interested in data-driven experimental design and the intersection between biotechnology and materials science.

No comments yet