Bacteria and their viral predator bacteriophages (phages) have coevolved for billions of years and are engaged in an endless arms race against each other. Bacteria, which are outnumbered by phages by about tenfold, have developed diverse defense systems to evade phage infection. These defense systems include the well-known restriction-modification (RM) and CRISPR-Cas systems, which can recognize and cleave invading phage DNA. To escape these defenses, phages have evolved multiple counter-defense strategies, and one of the most widespread is DNA modification to block bacterial RM and CRISPR-Cas systems. Cui and Dedon have developed technologies to discover and understand this weapon system.

The building blocks of DNA - nucleosides A, T, G and C - can be modified with chemical structures ranging from simple methylation to more complex hypermodifications such as glycosylation, the so-called epigenome. More than thirty DNA modifications have been defined in phages and bacteria so far, with many more modifications and modification systems yet to be discovered. The study of phage DNA modification systems will not only help us to better understand the complex epigenomic interactions between phages and their bacterial hosts, but also allow the development of more effective phage therapeutics against antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

Phage therapy against antimicrobial resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in bacterial pathogens constitutes one of the biggest public health crises of our time and could become the leading cause of death by 2050. AMR has rendered many antibiotics ineffective, and the combination of growing AMR with the decreasing rate of antibiotic discovery has motivated the development of new antibiotic alternatives.

One alternative exploits the bactericidal activity of naturally occurring phages, which have been used for a century to treat pathogenic bacterial infections. Among the advantages of phages over traditional antimicrobial drugs are their narrow host specificity, which avoids indiscriminate killing of normal body flora, and their relative safety compared to the toxic side effects of many small-molecule antibiotics. Nonetheless, there are limitations of phage therapy, including the development of phage resistance and the poor understanding of the complex interactions of phages with their bacterial hosts.

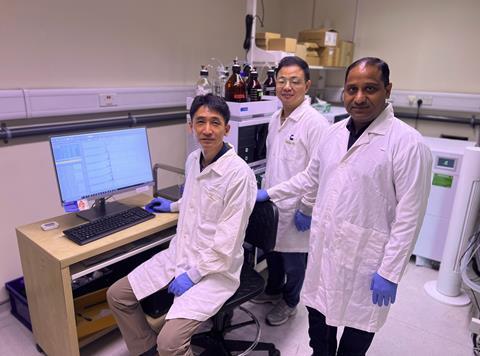

DNA modification discovery platform

About a decade ago, a team at the Dedon lab took up the challenge of discovering novel DNA modifications in both phages and bacteria. The tool used by the Dedon lab is a technology termed liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS). Cui has now developed a highly sensitive LC-MS-based DNA modification discovery platform, including targeted liquid chromatography triple-quadrupole mass spectrometry (LC-QqQ-MS) measurements of known DNA modifications and untargeted liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (LC-QTOF-MS) for the detection of novel DNA modifications. These innovative technologies have led to the discovery of more than ten new DNA modifications.

Most complicated DNA modification system

The initial work at the Dedon lab focused on a group of DNA modifications called 7-deazaguanine derivatives. These derivatives are known modifications of ribonucleic acids (RNA) with a well-established biosynthesis pathway. Through genomic data mining, the Dedon lab and the laboratory of Prof Valérie de Crécy-Lagard at University of Florida, USA, predicted that 7-deazaguanine derivatives could be inserted into DNA. Subsequent LC/MS analysis of DNA samples confirmed three 7-deazaguanine derivatives in different organisms, illustrating an unexpected evolutionary connection between DNA and tRNA metabolism. Cui applied their DNA modification discovery platform to more DNA samples from phages encoding at least one of the enzymes of this pathway and was able to detect and identify seven more 7-deazaguanine derivatives in phage DNA, making it one of the most chemically elaborate DNA modification systems found in nature thus far.

The finding of arabinosyl-hydroxyl-modifications in phage DNA

The most recent study, published in Cell Host & Microbe, focused on phage LC53, which infects Gram-negative bacteria Serratia, as a collaboration between the Dedon lab and Prof Peter Fineran’s lab at University of Otago, New Zealand. The Fineran lab studies the interactions between bacteriophages, other mobile elements, and their bacterial hosts, in particular in the area of CRISPR-Cas and other phage defense mechanisms. Prof Fineran found that phage LC53 possessed a mechanism to evade the DNA-targeting defenses, while remaining sensitive to RNA-targeting systems. LC53 encodes homologs of DNA modification enzymes reported to substitute the cytosine pool with arabinosyl-hydroxymethyl-cytidine (5ara-hmC). Surprisingly, upon LC/MS analysis of digested LC53 DNA, Cui found that LC53 contained a different and previously unreported DNA modification – arabinosyl-hydroxy-cytidine (5ara-hC). Subsequent LC/MS analysis of other arabinosylated phages showed that this modification can be further modified with one or two more arabinose sugars to form double or triple-arabinosylated DNA. Functional studies revealed that the modifications with more sugars could provide greater protection against bacterial defenses. More importantly, many of these modified phages target major pathogenic bacteria and show promise for developing new treatments against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

More phage DNA modifications are yet to be uncovered

The combination of analytical chemistry, computational prediction, and comparative genomics allowed Cui and Dedon, and their collaborators to systematically expand the repertoire of DNA modifications in phages, revealing that natural DNA phage modifications occur at a higher rate than previously predicted. This discovery uncovers the vast potential for discovering other novel phage DNA modification systems that will allow the development of more effective phage therapeutics or the genetic engineering of phages against antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

The research published in Cell Host & Microbe, conducted at Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART), is supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) Singapore under its Campus for Research Excellence and Technological Enterprise (CREATE) programme, and by the Agilent “Applications and Core Technology University Research” (ACT-UR) programme. The research conducted at University of Otago is supported by the Royal Society of New Zealand and the Tertiary Education Commission New Zealand.

No comments yet