Plant–microbe interaction studies have increased greatly in recent years. This sharp increase in studies is attributed to the need to better understand these interactions, which in turn can be used to enhance crop productivity and stress tolerance, reduce fertilizer inputs, and improve plant health. This is vital to meet the food demands of the growing global population. The world population has grown from 6.1 billion in 2000 to over 8 billion today and is projected to reach ~9.7 billion by 2050, demanding an estimated 60–70% increase in food production. At the same time, arable land per capita has declined by nearly 50% since 1960, while climate change continues to reduce crop yields in major agricultural regions. Plant–microbe interaction research is now viewed as a critical, sustainable strategy to meet rising food demands while minimizing environmental degradation.

Background

Plant-microbe interaction is a complex and dynamic relationship between plant and microbial communities. It can be beneficial (mutualistic), harmful (pathogenic), or neutral, forming vital “holobionts” that support plants by enhancing nutrient acquisition, producing growth-promoting hormones, improving tolerance to stresses such as drought and salinity, and protecting against pathogens. In return, plants supply microbes with carbon-rich compounds. Both the rhizospheric (near the root) and phyllospheric (upper plant) regions serve as a crucial interface for these interactions. This hidden partnership underpins a fundamental role in plant health, productivity, and ecosystem functioning.

In plant–microbe interaction research, bacteria and fungi have traditionally received the most attention because of their well-understood, significant benefits to plant growth and ecosystem health. Bacteria rapidly colonize the rhizosphere and endosphere, while mycorrhizal fungi – particularly arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and endophytic fungi –establish stable relationships with plants. Both types enhance plant nutrition and provide defence against pathogens through antibiosis, resource competition, and the induction of systemic resistance (ISR). Like most microbes, yeasts are highly adaptable, able to thrive in changing environmental conditions. Beyond just surviving, they produce a diverse range of novel compounds with uses in food, feed, agriculture, and environmental sustainability. Our team has been actively studying the complex interactions between yeasts and plants. “We are currently working on sharing our findings on the yeast microbiome of Avicennia officinalis, highlighting differences in taxonomic and functional composition across distinct plant compartments, with the global scientific community.”

Yeast-plant interactions

In recent years, yeast–plant interactions are gaining increasing importance because they fill critical functional and ecological gaps that are not fully addressed by bacteria and filamentous fungi. Research has found that the yeasts are resilient to stress, enabling them to endure extreme conditions such as high salinity, drought, UV exposure, and nutrient scarcity –conditions that are becoming more common due to climate change. This makes yeasts particularly effective in supporting plant growth in marginal soils, coastal ecosystems, and stressed agroecosystems.

Many plant-associated yeasts efficiently produce phytohormones, vitamins, antioxidants, siderophores, and biosurfactants, directly enhancing nutrient uptake, plant growth, and stress resilience. In addition, yeasts exhibit strong biocontrol potential by competing with pathogens, producing antimicrobial metabolites, and forming protective biofilms on plant surfaces, often without the ecological risks associated with some fungal biocontrol agents. Understanding these complex interactions is paramount, especially in the context of sustainable agriculture.

Factors influencing yeast-plant interactions

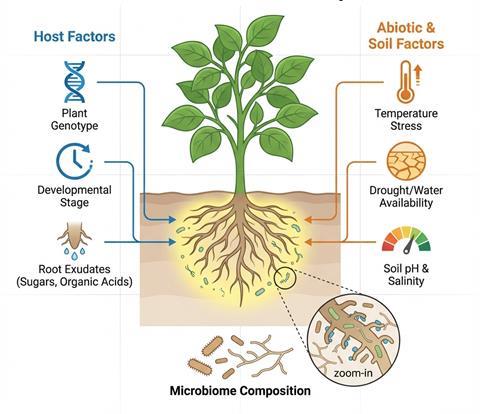

The composition of plant yeast biomes is determined by various plant-related factors, such as the genotype, organ type, species, and health, as well as environmental factors such as land use, climate, and nutrient availability. Some yeast communities are found very tightly associated with a plant species, termed the “core plant yeast biome”, while othersoccur at a lower frequency and are termed “satellite taxa”.

Host factors

Plants selectively recruit yeast communities based on species, genotype, organ, root architecture, and developmental stage, resulting in distinct and sometimes host-specific yeast assemblages. Root morphology and organ-specific traits create specialized niches that support diverse yeast populations, while root exudates rich in sugars, organic acids, phenolics, and secondary metabolites act as chemical signals that regulate yeast colonization and activity. Community assembly in the stem/bark is based on stochastic colonization (e.g., due to wind, rain, orinsects). Leaves harbour diverse communities of yeasts that form an important component of the phyllosphere microbiome. Leaf-associated yeasts utilize sugars, organic acids, and other compounds leached from plant tissues and can persist as epiphytes or occasionally as endophytes within leaf tissues. Nectar was once considered sterile; it is now recognized as a dynamic microbial habitat shaped by plant traits, pollinator activity, and environmental conditions. Among nectar-inhabiting microbes, yeasts are often dominant due to their tolerance to high sugar concentrations, osmotic stress, and fluctuating temperatures. These yeasts can rapidly colonize nectar after being introduced by pollinators such as bees, butterflies, and birds. Nectar-associated yeast significantly influences nectar chemistry by modifying floral scent and taste, thereby affecting pollinator behaviour, visitation rates, and ultimately plant reproductive success.

Edaphic factors

Soil pH, organic carbon content, C:N ratio, moisture, and nutrient availability (both micro and macro) regulate yeast survival and activity by imposing physiological constraints that favour stress-tolerant and metabolically versatile taxa. Among these factors, soil pH and carbon exert the strongest influence, shaping yeast community structure by altering substrate availability and environmental suitability.

Environmental factors

Changes in temperature, rainfall, and seasonal patterns influence plant physiology and surface chemistry, which in turn shape yeast recruitment and community structure. Among environmental factors, temperature and moisture exert the strongest effects, often regulating yeast abundance and diversity more profoundly than other variables. Abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, and heat further modify plant–yeast interactions by altering plant stress responses and exudation patterns, thereby selectively favouring stress-tolerant yeast taxa.

Impact of yeast-plant interactions on agricultural sustainability

Plants coexist with diverse microbial partners, and among them, yeasts play a dual yet largely beneficial role in shaping plant health and productivity. Through mutualistic and commensal associations, plant-associated yeasts contribute to sustainable agriculture by enhancing nutrient availability, producing growth-promoting metabolites, and improving plant stress tolerance. Many yeasts solubilize phosphorus, produce siderophores for iron acquisition, and synthesize phytohormones such as auxins and gibberellins, thereby regulating plant growth, development, and water stress responses. Yeasts also contribute to plant defense by inducing systemic resistance, forming protective biofilms, competing with pathogens for space and nutrients, and producing antimicrobial compounds and volatile metabolites. In addition, certain yeasts participate in rhizoremediation by tolerating and transforming pollutants, aiding soil health restoration under stressed and contaminated environments.

However, a small fraction of plant-associated yeasts may act as opportunistic or pathogenic organisms, causing tissue damage or disrupting plant physiological processes under favourable conditions. Such harmful interactions can negatively affect plant growth and yield, emphasizing the need for balanced microbiome management. Overall, beneficial yeast–plant interactions far outweigh negative effects, positioning yeasts as promising, eco-friendly tools for improving crop productivity, resilience, and sustainability in modern agricultural systems.

Yeast–plant interactions for functioning ecosystems

Yeast–plant interactions are integral to the functioning and resilience of natural and managed ecosystems. As versatile members of the plant microbiome, yeasts colonize roots, leaves, flowers, and surrounding soils, where they influence nutrient cycling, plant growth, and stress tolerance. By metabolizing plant-derived carbon compounds, producing phytohormones, antioxidants, and siderophores, and suppressing pathogens through competition and antimicrobial activity, yeasts contribute to plant fitness and community stability. In ecosystems exposed to environmental stress – such as salinity, drought, flooding, or pollution – stress-tolerant yeasts enhance plant survival and aid in soil recovery through detoxification and organic matter transformation. These subtle yet persistent interactions support primary productivity, regulate microbial balance, and strengthen ecosystem services, underscoring yeasts as key but often overlooked drivers of healthy, functioning ecosystems.

Omics-based approaches to dissect yeast-plant interactions

The study of these dynamics has been significantly advanced by omics technologies, which provide comprehensive insights into the genetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic. These sophisticated approaches allow for a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms. Moreover, unraveling the phenotypic diversity between ancestral and domesticated plant varieties, alongside characterizing fine-scale changes within the rhizosphere, is essential for identifying novel strategies to optimize plant-microbe interactions across diverse environmental conditions.

Conclusion

Beyond farms, plant–yeast interactions help maintain ecosystem balance by regulating nutrient cycles, supporting biodiversity, and improving soil health. As research progresses, these tiny partners are becoming key to strategies for sustainable food production and environmental protection. Understanding and utilizing plant–yeast relationships can guide us toward a greener, healthier future for both agriculture and the planet.

No comments yet