That distinctive “sea breeze” scent we associate with the coast isn’t just nostalgia; it’s the smell of microbial chemistry at work. Behind it lies an intricate web of microbial pathways turning sulfur compounds into gases that help shape Earth’s climate. Jeff D. Ojwach explores how discoveries are rewriting our understanding of this invisible but vital microbial process.

The scent of life

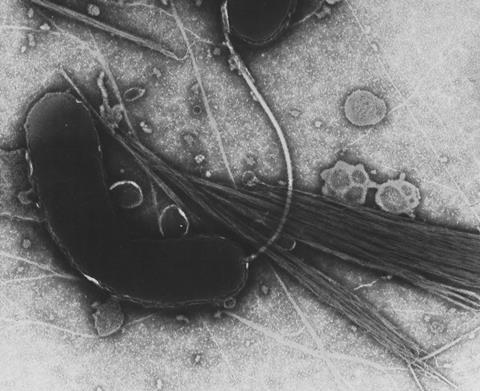

You can smell it before you see it, that unmistakable tang of the ocean. The smell of the sea, crisp and slightly sweet, is more than a sensory reminder of the coast. It’s the signature of dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a gas produced by microbes living in seawater, sediments, and even plant tissues. Each breath of that salty air carries the story of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), a sulfur compound synthesized by marine algae, seagrasses, and bacteria, then transformed by microbes into DMS. Once released, DMS rises into the atmosphere, forming sulfate aerosols that seed clouds and help cool the planet. The smell of the sea is, quite literally, the smell of microbes working behind the scenes to regulate Earth’s climate.

The invisible sulfur cycle

DMSP is among the most abundant organic sulfur compounds in the ocean. For algae and seagrass, it functions as an osmolyte and antioxidant, protecting cells against stress from salinity or light. When microbes metabolize DMSP, they set off a chain reaction connecting ocean ecosystems to atmospheric chemistry. Microbial conversion of DMSP to DMS contributes to a major flux of sulfur into the atmosphere and eventually, back to Earth via rainfall. This microbial–atmospheric feedback loop plays a subtle but significant role in Earth’s climate regulation. Yet despite decades of study, microbiologists are still uncovering new genes, enzymes, and pathways involved in DMSP cycling, revealing that this global process is far more diverse than once thought.

Beyond the usual suspects

For years, DMS production was attributed mainly to DMSP lyases, enzymes that cleave DMSP into DMS and acrylate, encoded by the Ddd genes (like dddP or dddL). Alternatively, some microbes use demethylase enzymes (the DmdA pathway) to channel DMSP’s sulfur into metabolism. However, recent discoveries suggest these are just part of the story. A new family of enzymes, including DMSOR (dimethyl sulfoxide reductase-like oxidoreductases), may transform DMSOP (dimethylsulfoxoniopropionate) into DMS through previously unrecognized reactions.

These alternative pathways, observed in some Gammaproteobacteria, hint that multiple biochemical routes coexist and respond dynamically to environmental cues. The finding broadens our understanding of how microbes contribute to DMS fluxes and challenges long-held assumptions about sulfur metabolism in marine ecosystems.

From sea to soil

Once thought to be confined to marine systems, DMSP has now been detected in a surprising array of terrestrial plants, including halophytes like Sueda and Atriplex, as well as crops such as sugarcane and maize. In these plants, DMSP likely helps with osmotic and oxidative stress tolerance, particularly under drought or salinity stress. Equally intriguing is that some soil bacteria carry DMSP transporter genes but lack the classical lyase or demethylase enzymes. This suggests they might import and process DMSP via as-yet-unidentified metabolic routes or use it as a signaling molecule in plant-microbe interactions. Together, these findings hint at a continuum between marine and terrestrial sulfur cycles, revealing DMSP as a molecule that links ecosystems across boundaries.

Tools of discovery

Uncovering these hidden pathways requires a blend of genomic, chemical, and ecological tools. Researchers use metagenomics to identify new DMSP-related genes in environmental samples and DNA- RNA- stable isotope probing (SIP) to track how labeled 13C-DMSP moves through microbial communities. In controlled experiments, gas chromatography with flame photometric detection (GC-FPD) measures the release of volatile sulfur compounds such as DMS and methanethiol (MeSH) while NMR spectroscopy confirms chemical transformations in culture supernatants. By combining these methods, microbiologists can connect genetic potential with real biochemical activity, revealing not just who’s there, but what they’re doing.

Microbes and climate: a delicate balance

The microbial sulfur cycle is not just a curiosity of marine chemistry; it’s a vital component of Earth’s climate engine. DMS released by microbes acts as a natural coolant, influencing cloud cover and radiation balance. Some have proposed that microbial DMS emissions could even provide negative feedback against global warming, although the extent of this effect remains debated.

”What is clear is that climate change will, in turn, reshape the microbial world.”

Warming oceans, nutrient shifts, and altered vegetation may change how and where DMSP is produced and degraded. Predicting those changes requires better integration of microbial processes into climate models, a challenge that’s only now gaining momentum.

The next frontier

The future of this field lies in connecting genes, functions, and ecosystems. Scientists are beginning to ask fundamental questions: How do microbial communities coordinate sulfur cycling collectively? Is there feedback between DMSP metabolism and other biogeochemical processes, like nitrogen or carbon cycling? How widespread is DMSP metabolism, i.e., in marine, terrestrial environments, or the gut ecosystems of animals or humans? By combining multi-omics data, isotopic labeling, anaerobic culturing, and ecological modelling, the next generation of researchers is poised to uncover how these microscopic chemists sustain the planet’s balance.

The scent of connection

Next time you walk along the shore and breathe in that familiar “sea air,” you’re smelling the work of billions of microbes, a living network connecting seagrasses, sediments, soils, and the atmosphere above. That faint whiff of sulfur isn’t just the smell of the sea. It’s the scent of life itself, microbes writing their chemical signature into the story of our planet.

Further reading

Acknowledgements

The Norwich Research Park Biosciences Doctoral Training Partnership (NRP DTP).

No comments yet