The idea that herpes infections trigger or contribute to Alzheimer’s disease has been gaining favor among some scientists, raising hope that herpes treatments could slow progression of Alzheimer’s symptoms among patients.

But the first clinical trial to test that theory has found that a common antiviral for herpes simplex infections, valacyclovir, does not change the course of the disease for patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s.

Results from the trial, led by researchers at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, were presented July 29 at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

READ MORE: Cold sore viral infection implicated in development of Alzheimer’s disease

READ MORE: Herpesviruses may contribute to Alzheimer’s disease via transposable elements

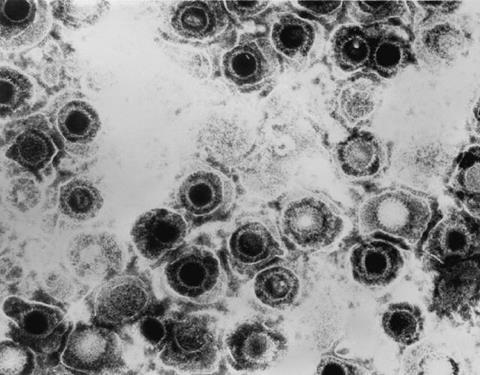

Approximately 60% to 70% of Americans are infected with herpes simplex viruses, which cause cold sores (usually HSV1) and genital herpes (HSV2). After signs of the initial infection subside, the viruses remain dormant within the nervous system and can periodically reactivate, causing symptoms to flare up.

Various studies have found connections between herpes infections and Alzheimer’s, including an autopsy study that found HSV1 DNA was often associated with amyloid plaques in the brains of people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Additional studies have found that people treated for herpes infections were less likely to be later diagnosed with Alzheimer’s than HSV-positive people who received no antiviral treatment.

Hope for patients

“Based on those previous studies, there was hope that valacyclovir could have an effect,” says the trial’s lead investigator, D.P. Devanand, MD, professor of psychiatry and neurology and director of geriatric psychiatry.

“But no one had conducted a clinical trial to test the idea.”

The trial included 120 adults, age 71 on average, all diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment with imaging or blood tests that indicated Alzheimer’s pathology. All participants had antibodies revealing past herpes infections (mostly HSV1, some HSV2).

The participants were randomly assigned to take daily pills containing either valacyclovir or a placebo. The researchers measured the patients’ memory functions and imaged the brain to look for amyloid and tau deposits associated with Alzheimer’s and other structural changes.

No signal

After 18 months, the researchers found that patients taking the placebo performed slightly better on cognitive tests than the valacyclovir group, but no other measures were significantly different.

“We were looking for a signal that the drug did better than the placebo, but there wasn’t any in this study,” Devanand says. “On the other measures, sometimes the placebo group did slightly better, sometimes the treatment group did slightly better.”

Grouping participants by age, sex, and apolipoprotein E e4 status did not affect the results.

“Our trial suggests antivirals that target herpes are not effective in treating early Alzheimer’s and cannot be recommended to treat such patients with evidence of prior HSV infection. We do not know if long-term antiviral medication treatment following herpes infection can prevent Alzheimer’s because prospective controlled trials have not been conducted.”

Additional information

The study, titled “Antiviral Therapy: Valacyclovir Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease (VALAD) Clinical Trial, was presented July 29 at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Toronto, Canada.

Authors: Davangere P. Devanand (Columbia University), Thomas Wisniewski (New York University Medical Center), Qolamreza Razlighi (Weill Cornell Medical Center), Min Qian (Columbia), Renjie Wei (Columbia), Edward P. Acosta (University of Alabama), Karen L. Bell (Columbia), Allison C. Perrin (University of Arizona), and Edward D. Huey (Alpert School of Medicine of Brown University).

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01AG055422 and P30AG066512) and the Alzheimer’s Association.

No comments yet