Researchers from Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine and collaborating Japanese institutions found that patients carrying colibactin-producing Escherichia coli (pks+ E. coli) in their colon polyps were more than three times as likely to have a history of colorectal cancer compared to those without the bacterium.

The findings, published in eGastroenterology, highlight a potential role for gut microbes in accelerating cancer risk in people with a strong genetic predisposition.

Between 2018 and 2019, the team studied 75 FAP patients who had not yet undergone colon surgery, preserving their natural gut microbiota. Tissue samples from colon polyps and surrounding mucosa were collected during endoscopy and analyzed for pks+ E. coli.

Key results include:

- High prevalence: The bacterium was found in a substantial proportion of patients, especially smokers.

- Surgery effect: No pks+ E. coli was detected in patients who had previously undergone colorectal surgery, suggesting that an intact microbiota is required for colonization.

- Cancer link: Among non-surgical patients, those with prior colorectal cancer were over three times more likely to carry pks+ E. coli (risk ratio 3.25).

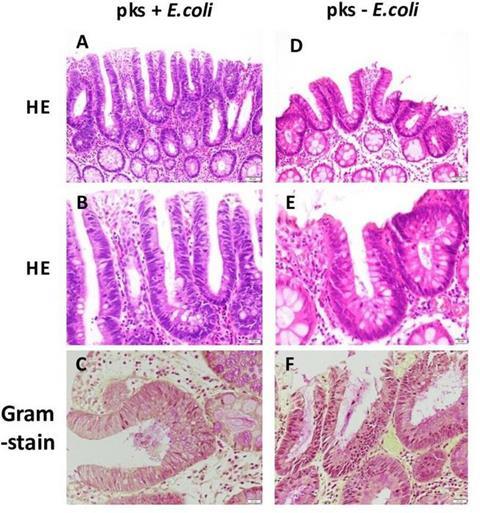

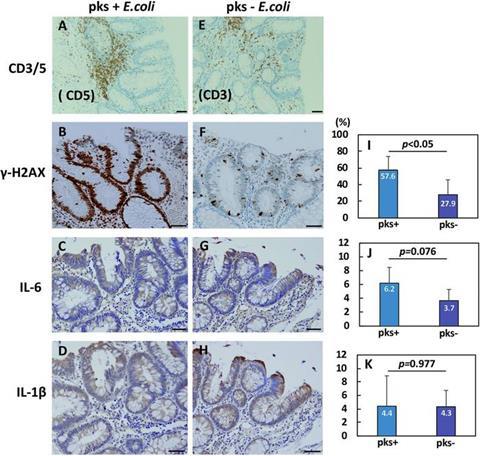

- Tissue changes: Adenomas harboring the bacterium showed more DNA damage and signs of inflammation, including elevated IL-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine.

This study raises the possibility that targeting specific microbes could help prevent cancer in high-risk groups. The researchers propose that colibactin, a toxin produced by the bacterium, damages DNA and triggers inflammatory signals that may accelerate tumor progression in the already vulnerable colonic tissue of FAP patients.

Looking ahead

The study is among the first to examine the role of gut bacteria in FAP patients before surgery, offering a rare glimpse into the natural microbial environment of this population.

The authors caution that the findings are preliminary and based on a relatively small patient group. Larger, multicenter studies are needed to confirm the results. If validated, the research could pave the way for new approaches, such as:

- Microbiome-targeted prevention (probiotics, bacteriophages, or antibiotics).

- Risk screening through bacterial detection in stool or mucosal samples.

- New therapies targeting colibactin-induced DNA damage and inflammation.

The study provides early but compelling evidence that colibactin-producing E. coli may play a role in colorectal cancer development in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. By shining light on the interplay between genes, microbes, and environment, the findings open new avenues for cancer prevention strategies in hereditary syndromes.

No comments yet