Since the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was identified in 1983, roughly 91.4 million people around the world have contracted the virus and an additional 44.1 million have died from related causes. Currently, nearly 40 million people worldwide are living with HIV-1, the version of the virus that causes more than 95% of infections.

While significant progress has been made in HIV vaccine research, according to Penn State Professor Dipanjan Pan, there is currently no approved vaccine for HIV. Research is ongoing, though, he said, with multiple preventive and therapeutic strategies under investigation — but some vaccine candidates can cause participants to falsely test HIV-positive, complicating diagnosis and clinical management.

READ MORE: $2.7 million NIH grant to fund first comprehensive syphilis test

READ MORE: First rapid test for mpox can be tailored for other emerging diseases

To solve this issue, Pan and his team developed a new approach capable of differentiating active HIV infection from false positives — which could potentially accelerate vaccine development and testing, Pan said. The researchers partnered with the HIV Vaccine Trials Network, which is sponsored by the National Institutes of Health’s Vaccine Research Center, to test 104 human blood samples with their new device.

The device, which employs a combination of analyses to produce results in just five minutes, correctly identified those with active HIV-1 infection 95% of the time and those without active infection but with vaccine-induced molecules that could trigger a false positive, 98% of the time. That’s on par or better than every current approach, Pan said.

The researchers published their work today (Dec. 3), for which they have also filed a patent, in Science Advances.

Global burden

“Despite continuous advancements in prevention and treatment, HIV remains a significant global health issue,” said Pan, the Dorothy Foehr Huck & J. Lloyd Huck Chair Professor in Nanomedicine and professor of nuclear engineering and of materials science and engineering. “Given this global burden, developing safe and effective vaccines is crucial for reducing HIV transmission rates and ultimately managing the epidemic.”

HIV vaccines under development are intentionally designed to induce the production of antibodies that target key HIV antigens, which are proteins on the virus’s surface that identify it as a threat to the immune system. Antibodies can bind to these antigens and help render the virus inert, meaning it can no longer infect a host’s cells. The antigens are also what diagnostic tests detect to confirm an infection.

“A direct consequence of this immunogenic overlap is that the vaccine can make a person test positive for HIV-1, even when they do not have the infection,” Pan said, explaining that this phenomenon is called vaccine-induced seroreactivity or seropositivity (VISP) and refers to positive results on serologic — components of blood — antibody-based HIV tests. “This poses serious social, professional and personal consequences for those individuals. It can also make trial results difficult to interpret, slowing the progress toward widely available HIV vaccines.”

False positives

According to Pan, across various HIV vaccine trials, false positives or VISP occurs in anywhere from .4% to 95% of tests. The broad range depends on patient demographics, types of diagnostic tests used, vaccine design and several other variables. This is further complicated by seroreactivity, or the presence of antibodies in a blood sample that are left over from a vaccine-induced immune response or a prior infection. Like VISP, seroreactivity can also trigger false positives with antibodies persisting for more than two decades in some cases.

“VISP and seroreactivity are not just technical nuisances; they can lead to ongoing misdiagnosis with broad effects on individuals and populations, such as psychological distress and societal challenges, including misunderstanding within families and communities,” Pan said. “They can also create logistical barriers, especially for health care workers who might be disqualified from donating blood, bone marrow or other organs and face additional complications with insurance, military service, employment, travel, immigration or pregnancy.”

Pan noted that VISP is often perceived as a risk for participating in vaccine trials, which limits recruitment. Once a vaccine is approved and administered, Pan said, the issue doesn’t abate, as VISP could skew HIV incidence data; necessitate unnecessary medical follow-up or treatment; complicate population vaccination efforts; or even obscure genuine HIV infection outbreaks.

Multistep programs

Current diagnostics in HIV vaccine trials employ multistep programs that are often costly, in terms of time and money. Even then, the most accessible process to distinguish VISP or seroreactivity from true infection uses a nucleic acid amplification test, which requires specialized equipment and trained personnel.

“The development of a rapid, affordable and reliable point-of-care diagnostic tool capable of distinguishing immune-induced responses from active HIV infection is essential to support the broader deployment of HIV vaccines and to address the limitations of existing technologies,” Pan said. “To address the laboratory testing challenges posed by this problem, we developed a test that simultaneous detects protein and nucleic acid markers within a single device.”

Two test strips

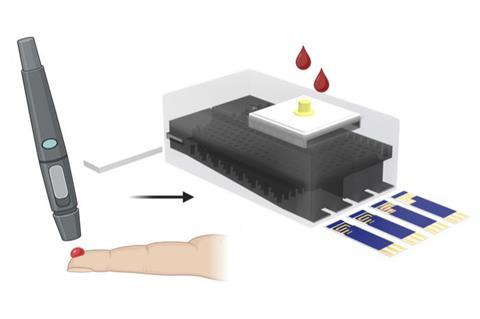

The 3D-printed device allows plasma from a blood sample to filter through tiny channels that direct it over two test strips at the same time. One strip can detect two protein biomarkers elicited by HIV-1 antibodies, either via infection or vaccination. The other strip can detect the genetic material — RNA — in HIV-1 virus particles.

“That’s the key innovation in overcoming the critical limitation of conventional antibody-based diagnostics,” Pan said. “By incorporating HIV-1 RNA detection, the testing platform provides a definitive indicator of active viral replication, which is absent in VISP cases. As such, this test can accurately discriminate between vaccine-induced responses and true infection.”

From the HIV Vaccine Trials Network, the team tested their device with 104 clinical samples representing four groups: HIV-negative, non-vaccinated; HIV-negative, undergoing vaccination trial; HIV-positive, non-vaccinated; and HIV-positive, vaccinated. Using AI, the device can analyze a sample in five minutes with highly accurate sensitivity for every potential combination in the clinical population, Pan said.

“Our proposed all-in-one testing platform represents a substantial advancement in HIV diagnostics, enabling accurate detection of active HIV infection while minimizing false positives due to VISP,” Pan said. “The scalable design and relatively low-cost of the device make it an appealing solution for widespread adoption in both resource-rich and resource-limited environments.”

Next steps

Next, Pan said, the team will refine their prototype to make it more durable and extend its ability to screen for other pathogens. He also noted that they are envisioning a spin-off at-home viral load test to determine how much of the virus is present in a person’s body. Such a test could potentially benefit HIV patients undergoing antiretroviral therapy, which uses a combination of approaches to suppress the virus and stop viral replication.

Pan also has affiliations with the Departments of Chemistry, Biomedical Engineering and of Radiation Oncology at Penn State. Other contributors currently affiliated with Penn State include Ketan Dighe and Nivetha Gunaseelan, doctoral students in biomedical engineering; Maha Alafeef, who was a researcher in nuclear engineering; Teresea Aditya, assistant research professor of nuclear engineering; and Pranay Saha, postdoctoral research associate in nuclear engineering; David Skrodzki, graduate research assistant in materials science and engineering; and Casey Pinto, associate professor of public health sciences. Oguzhan Colak, research scientist at Vitruvian Bio who earned a doctorate in materials science from Penn State in 2024; Parikshit Moitra, who was a research assistant professor of nuclear engineering at Penn State at the time of the research and is now an assistant professor at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research; and John Hural, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, also co-authored the study. Dighe, Colak, Moitra, Alafeef, Skrodzki, Aditya, Saha and Gunaseelan are also affiliated with the Penn State Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, and Alafeef is also affiliated with the Jordan University of Science and Technology.

The National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and National Institute of Mental Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. National Science Foundation and the Department of Defense’s Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program funded this research.

No comments yet