In the hunt for a remedy, when the baton is passed from dedicated academic scientists to an innovative company to trusted community advocates, outcomes for society can be especially powerful.

Today, thanks to that sequence of contributions, the first HIV drug to offer long-lasting protection from infection — eliminating the need for people to take a daily pill — exists. For their role in ensuring that drug, lenacapavir, came to life and to market, the AAAS Mani L. Bhaumik Breakthrough of the Year Award is being awarded to Wesley Sundquist, chair of the University of Utah Department of Biochemistry; Moupali Das, vice president, Clinical Development, HIV Prevention & Pediatrics at Gilead Sciences; and Yvette Raphael, co-founder and executive director of Advocacy for Prevention of HIV in Africa.

READ MORE: Research reveals how lenacapavir pushes HIV capsid to breaking point

“These individuals represent the three arms of what is necessary to create new science and then translate it for the world in a way that is really able to make a difference,” said Megan Ranney, dean of the Yale School of Public Health and part of the committee — convened by Science journals’ Editor-in-Chief Holden Thorp — that selected the winners.

“I was excited about how these three tell the story of the journey required to bring a drug into existence,” said committee member William Powderly, co-director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Washington University School of Medicine. “It takes multiple people, skillsets and partners.”

Global threat

As of 2023, 39.9 million people globally were living with HIV, newly infecting more than 1 million people a year.

Even after decades of research, there is no cure for the disease HIV causes, AIDS. But lenacapavir, born out of research on HIV’s cone-shaped capsid protein, gets close, almost completely preventing new HIV infections from occurring. The drug protects people for six months with each shot.

“This drug is extraordinary — the closest thing to a vaccine that we have,” said Ranney. She explained that she and many of her peers in the public health community entered the field at the height of the AIDS pandemic, in the 1980s and 1990s. “This medication is beyond the wildest dreams of what many of us could have imagined.”

Closest thing to a vaccine

Recognizing the people behind such significant scientific developments is a central philosophy for donor Mani L. Bhaumik, Ph.D. — a physicist with myriad contributions to the development of high-powered lasers — as well as for AAAS and the Science family of journals.

The Mani L. Bhaumik Breakthrough of the Year Award was established in 2022 with a $11.4 million pledge from Bhaumik: the largest in the organization’s history. The award supports a $250,000 cash prize annually for up to three scientists or researchers whose work best underpins the Science Breakthrough of the Year, the journal’s choice of the top research advance of the year. In 2024, Science named lenacapavir the latest Breakthrough.

Mapping HIV’s capsid

Sundquist, who moved to the University of Utah as an assistant professor in 1992, played a key role in the development of the drug, though his work was not immediately recognized. “Sundquist spent countless hours in the lab, made a critical discovery, and then watched it sit on the shelf for a while, which can happen in basic science,” said Ranney.

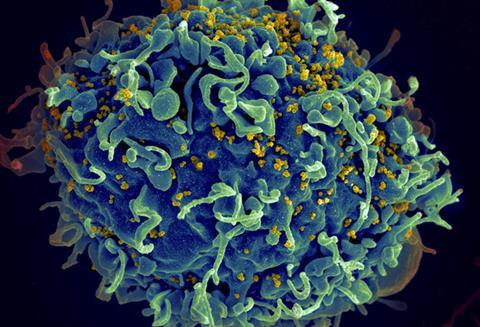

His contribution — which he embarked upon as he started his Utah-based lab — was elucidating the structure and functions of the HIV virus’s capsid protein. Sundquist focused on the capsid because he was aware that HIV deaths were increasing globally and that most scientists studying HIV treatments were looking at the virus’s enzymes. “We wanted to work on an aspect of the problem that was unique,” he said, “and we were drawn to the unusual cone-shape of the capsid.”

Until Sundquist’s work, scientists thought the capsid, which encloses the virus’s genetic material, was largely a structural element. They did not see it as a particularly “druggable” target, especially compared to enzymes, in part because it was thought to be highly stable.

Capsid architecture

In 1996, working with a team, Sundquist published a paper in Science that defined the capsid’s architecture. That laid the groundwork for a study in 2003 in the Journal of Virology, in which he and colleagues showed that if the HIV capsid was disrupted, even in minor ways, viral replication was disrupted too.

“That was unexpected,” said Sundquist.

Even as these critical discoveries were made, however, it wasn’t obvious that the capsid would be easily turned into a drug target. For his part, though, Sundquist didn’t feel it was very long after he and his colleagues published their 2003 results that Gilead Sciences contacted them.

Tomas Cihlář, a virologist at the company, visited Sundquist’s labs. Impressed with his discoveries, Cihlář took them back to his colleagues. The Gilead team wanted to see if they could use Sundquist’s insights about how to hinder viral replication to design HIV drugs with longer acting power for people living with HIV; while the standard of care treatment — combination antiretroviral therapy — worked well, it required daily medication.

Search for a drug

A dedicated group of scientists at Gilead Sciences showed perseverance as it took more than a decade (beginning around 2006) to develop a drug based on Sundquist’s findings. To do so, John Link, then-vice president of Medicinal Chemistry at Gilead, and his colleagues screened thousands of molecules to identify an effective capsid inhibitor.

“We sometimes think about industry as not having staying power,” said Ranney. “But it was something like 15 years here — fits and starts — and Gilead as an institution kept supporting capsid inhibitors.”

The molecule’s properties meant its effects could be extended over six months, a promising option for patients who struggled with daily medications.

First trials

Gilead ran the first trial for people with HIV involving an injectable version of lenacapavir in 2018. “I was a medical monitor for the first Phase 1 trial,” said Das, a winner of this year’s Bhaumik Breakthrough of the Year Prize on behalf of the many Gilead Sciences team members working on lenacapavir. This meant Das, a trained physician, provided expert guidance to confirm the safety of trial participants.

At that time, Gilead was focused on evaluating lenacapavir for treatment of HIV. But the reality was there were already effective treatments, like antiretrovirals. Meanwhile, there were still many people in the world at high risk of acquiring HIV.

“I remember seeing results from the first lenacapavir treatment study and thinking this drug — because of its molecular properties — might be very good for prevention, too.” Das said, “I was immediately thinking: how could we use this for prevention?”

Next big step

The next step forward was figuring out the best way to evaluate this drug for preventing HIV.

“Gilead had already established the company as leaders in the use of oral antiretroviral agents as pre-exposure prophylaxis” said Myron Cohen, director of the Institute of Global Health and Infectious Diseases at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and who also sat on the committee who selected the winners. “But many people found it difficult to maintain usage of daily oral pills. Development of long-acting agents, especially injectable agents, became an important goal.”

When Gilead Sciences made this decision, Das played a crucial role. “She was the pivotal person who created studies to garner proof that it worked for prevention, too,” said Powderly.

Her leadership was essential in designing the clinical trials, known as PURPOSE 1 and PURPOSE 2, which began in 2021 and are among the most comprehensive HIV prevention trial programs ever conducted. The trials were carefully shaped to include people most in need of preventative care — and people most underserved by past trials. This involved establishing trial sites in locations where infections were happening most.

Changing hearts and minds

“There were lots of times where we had to change hearts and minds in designing this trial program because we did a lot differently,” she said. Much of this related to the novel design and lenacapavir itself, but also to who was included.

Das recalled a story of a young African adolescent woman who was pregnant and who came to a stakeholder meeting in Kigali, Rwanda. That meeting, organized by Gilead, included community advocates, government officials, regulators, ethicists, site staff and Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis clinical trial investigators whom Gilead had convened to discuss how best to design and implement PrEP trials in cisgender women.

“’Make sure people like me have a chance in the trials,’ this woman had said to us. I’ll never forget her.”

Good science

Das firmly believes better science happens when everyone is included. “It’s not charity,” she said. “It’s good science.”

The PURPOSE 1 trial evaluated lenacapavir in cisgender women and in adolescent girls in sub-Saharan Africa and Uganda, where stigma means some women have challenges using daily oral PrEP products. Some of the women in the trial became pregnant. Results from PURPOSE 1, published in July 2024, showed that twice-yearly lenacapavir led to 100% efficacy in preventing infections, a tremendous result. “It was so exciting to have the first results for lenacapavir for HIV prevention be in women,” said Das.

For PURPOSE 2, Das and her team recruited participants from places disproportionately affected by HIV and underrepresented in past HIV clinical trials, including parts of the United States, Brazil, Thailand, South Africa, Peru, Argentina, and Mexico. The trial evaluated lenacapavir for prevention of HIV in a diverse range of cisgender men and gender-diverse people. Results, published in November 2024, showed the drug reduced new infections by 96%.

Powderly said years-long work from researchers at Gilead Sciences leading up to Das’s efforts was critical, “and without her enthusiasm and drive, that final hurdle — the studies and trials for prevention — would have been much harder.”

’The human voice matters’

Keeping the people most in need of HIV drugs at the center of the PURPOSE trials, as Das did, was possible because of a key partner — another winner of this year’s Bhaumik Breakthrough of the Year Award: Yvette Raphael.

Das and Raphael met in Kigali, Rwanda in 2019, two years before the PURPOSE trials started, at the same stakeholder meeting where Das and the group convened by Gilead heard from the young pregnant African woman about including people like her in the trials. “Yvette really wanted to know what we were going to do differently,” said Das.

Raphael, an HIV prevention advocate and community leader living with HIV, had previously engaged in trials of HIV drugs. “We knew past trials had made mistakes,” she said.

“Raphael was well-recognized as a tireless and thoughtful advocate for the development of HIV prevention strategies for women,” said Cohen. “Her involvement in the development of lenacapavir – in trusted communication with Gilead and trial participants and their communities – was a critical requirement for the success of these studies.”

Access to information

Raphael fought to make sure people affected by HIV had access to information about new treatment options, including long-acting treatments that could improve quality of life. In Africa, especially among African women, problems with HIV preventative strategies — largely in the form of daily pills — were ongoing. Drugs that worked in men were not working in women in part because it was harder, for social reasons, for women to take a pill every day.

“An injection would have been better for women,” said Powderly. “But community trust and involvement were critical.”

Raphael, who served as Chair of the PURPOSE 1 Advisory Board from 2019 to 2024, told Gilead about the major challenges in the African community.

Young patients

“For lenacapavir trials, we wanted young people to be part so that the drug could be approved for them from the start,” said Raphael. Since young people need parental consent, she helped advise parents considering whether their adolescent children could participate.

“It was also very important for pregnant women to be included,” said Raphael. “We wanted to be sure that once this drug was approved, pregnant women could get it, too.”

Their efforts paid off, and the PURPOSE 1 trial came together, including women, pregnant women and adolescents.

Human voice

“The clinical trials would never have been as successful as they were had it not been for Raphael,” said Thorp.

“The human voice matters as much as the science to get to translation in the real world,” said Ranney. “Yvette’s leadership is a gorgeous exemplar of how great science is done.”

For her part, Raphael said her collaboration with Das, where they both learned from and pushed each other, was critical.

“I’d like to recognize Moupali’s fearlessness for creating greater participation from the community,” said Raphael. “We called her the ‘Das-rupter’ … I’ve been participating in HIV prevention trials for 25 years, and every time, we said we’d do better. I think with Moupali, this is the best we have done.”

Owning innovations

Ensuring that the people most impacted by a drug are part of trials provides another benefit that comes later. “We can discover drugs and see they are successful in trials, but the next outcomes won’t be as good if there’s nobody to ‘own’ these innovations, and to advocate for them to be affordable and accessible,” said Raphael. ”We did not want this drug to sit on a shelf.”

For Raphael, the outcome of the trials has been nothing short of a miracle. “It’s amazing that you need injections just twice a year.” She said the biggest surprise to her was the 100% efficacy in PURPOSE 1. “It was also surprising that it was such a short trial.” In 2024, the trial was stopped early because of success it had already shown, which meant the drug could become available sooner. “When that news broke,” she said, “Africa stood still.”

“The PURPOSE 1 and 2 trials are exemplars for how to do a better job making sure people who will one day want to use the medication have a voice,” said Ranney. “This will speed the implementation of the drug on the other side.”

Life-changing drug

Raphael knows the research that made this life-changing drug a reality started decades ago, in Sundquist’s lab, with studies of a viral capsid.

“This work changed how people think about viral capsids,” said Sundquist. “It meant that other people could think about capsids as drug targets.”

Today, however, as funding cuts to basic research are happening across the U.S., there is growing concern. “If there’s a weakness in the pipeline and people don’t know what to target,” said Sundquist, “then drugs don’t get developed.”

“My worry as we watch funding to science get cut,” said Ranney, “is we won’t fully feel the ripple effects for 10 or 20 years because it can take that long for discoveries to make their way into lives of families and individuals.”

Tomorrow’s breakthroughs

Raphael is concerned that cuts mean “life-saving drugs will fall out the window.” While lenacapavir is likened to a vaccine for HIV, it is not one. “This is not the last breakthrough for HIV prevention. Without continuous funding for prevention and advocacy, we won’t have tomorrow’s breakthroughs,” she said.

Programs like the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR — which has been a key component of global health since it was founded by President George W. Bush in 2003 — are critical to supporting HIV prevention. A study published in Annals of Internal Medicine in February of this year reported that eliminating PEPFAR would lead to 601,000 HIV-related deaths and 565,000 new HIV infections in South Africa alone over 10 years.

Freedom for science

As of April 30, 2025, PEPFAR’s current short-term authorization has expired. “The logical funding for distributing lenacapavir in the developing world would come from PEPFAR, a program that has been very successful, saving so many lives, but is now basically on life support,” said Sundquist. “This means lenacapavir is really at risk of not being broadly distributed in the places that need it the most.”

Ranney said her hope is that the selection of winners for this year’s prize serves to remind science funders of the importance of all stages of scientific innovation and of giving freedom to science to pursue great ideas. “It’s important to fund basic research as we never know what is going to be the next world-changing discovery.”

Topics

- AAAS Mani L. Bhaumik Breakthrough of the Year Award

- Advocacy for Prevention of HIV in Africa

- capsid

- Gilead Sciences

- HIV

- John Link

- lenacapavir

- Mani L. Bhaumik

- Medical Microbiology

- Megan Ranney

- Moupali Das

- Myron Cohen

- One Health

- People News

- PEPFAR

- Pharmaceutical Microbiology

- Tomas Cihlář

- University of North Carolina

- University of Utah

- USA & Canada

- Viruses

- Washington University

- Wesley Sundquist

- William Powderly

- Yale School of Public Health

- Yvette Raphael

No comments yet