Researchers from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have discovered a previously unknown mechanism that explains how bacteria can drive treatment resistance in patients with oral and colorectal cancer. The study was published in Cancer Cell.

Tumor-infiltrating bacteria have been known to impact cancer progression and treatment, but very little is understood about how they do this. The new study shows how certain bacteria – particularly Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn) – can induce a reversible state, known as quiescence, in cancer epithelial cells. This allows tumors to evade the immune system and resist chemotherapy.

READ MORE: Bacteria subtype linked to growth in up to 50% of human colorectal cancers

“These bacteria-tumor interactions have been hiding in plain sight, and with new technologies we can now see how microbes directly affect cancer cells, shape tumor behavior and blunt the effects of treatment,” said corresponding author Susan Bullman, Ph.D., associate professor of Immunology and associate member of MD Anderson’s James P. Allison Institute. “It’s a whole layer of tumor biology we’ve been missing and one we can now start to target. We hope these findings help open the door to designing smarter, microbe-aware therapies that could make even the toughest cancers more treatable.”

Evading detection

The study describes how a bacterium can enter tumors and surround tumor epithelial cells, effectively cutting off their communication with surrounding cells and causing the cancer cells to enter a temporary resting state known as quiescence. This, in turn, allows them to evade the immune system, resist chemotherapy and promote metastasis.

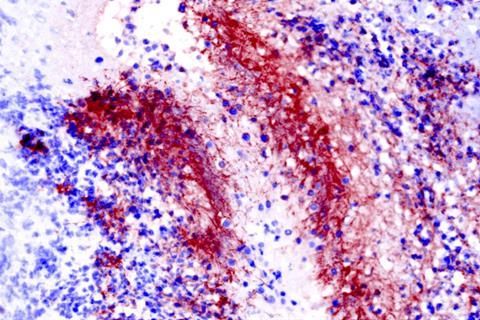

Researchers discovered this ability when they first noticed that Fusobacterium is enriched in areas of the tumor with reduced epithelial cell density and decreased transcription activity.

Preclinical models showed that Fusobacterium accumulates in specific parts of the tumor, settling between cancer cells, interfering with them, and making them less vulnerable to certain chemotherapies.

Spatial analysis validated these findings both in vivo and in a cohort of 52 patients with colorectal and oral cancer. In an independent patient cohort, higher levels of this bacterium were associated with lower expression of genes that allow for immune detection and with reduced treatment response.

Microbes and cancer

At MD Anderson, the Bullman and Johnston labs are uncovering how microbes like Fn influence treatment resistance and tumor progression in gastrointestinal cancers. This lays the groundwork for new strategies to counteract microbial effects on cancer.

In parallel, their teams also are exploring ways to engineer tumor-targeting bacteria as a future therapeutic tool. This approach, sometimes called using “bugs as drugs”, offers a promising way to overcome the barriers posed by solid tumors, which often are resistant to traditional therapies.

The study was limited by the fact that the experimental conditions, including laboratory bacterial doses and oxygen levels, may not fully capture the complex and dynamic environment within human tumors. This highlights the need for further research to better understand these interactions in vivo.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (R01CA288827, R01CA289812) and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR240035). For a full list of collaborating authors, disclosures and funding sources, read the full paper in Cancer Cell.

No comments yet