I remember one summer afternoon as a teenager, buying second-hand schoolbooks and finding a rugged veterinarian handbook on parasitic infections – it felt like I’d found a treasure someone had misplaced. Little did I know that the enthusiasm for tiny and weird critters would lead to a journey where years later I would get to investigate microbes in and on sea turtles.

My scientific endeavours started before my PhD and involved studying secretion systems in Escherichia coli at Uppsala University in Sweden. My mentors at the time quickly showed me the beauty of molecular biology, the fun of brainstorming, and the misery of empty agarose gels. Despite the charm of E. coli (and Swedish fika), during undergraduate studies, I kept being drawn to studying the impact of microbiomes on their host, and I wasn’t picky. Any host would do.

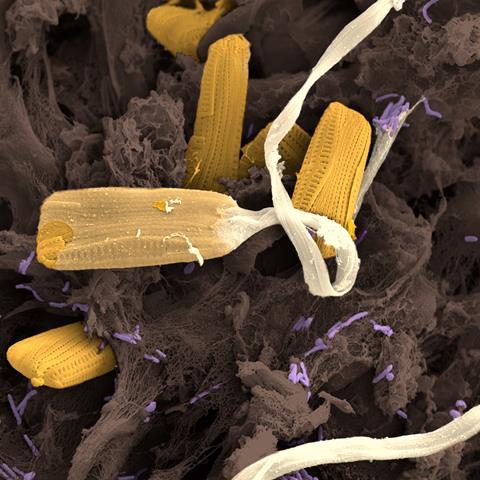

Luckily a project, established by my soon-to-be-PhD-supervisor Sunčica Bosak, focused on sea turtle-associated microbes (TurtleBIOME) and there was enough room for another PhD student. A whole new dimension of microbes was presented to me, as in TurtleBIOME we studied both diatoms and bacteria. Just a couple of years prior to starting this project, diatoms were discovered to inhabit the surfaces of every sea turtle species, with some diatoms exhibiting host specificity. As most sea turtles are endangered (but resilient!), this had great implications for using diatoms as markers of geography and possibly even health status within conservation efforts. Studying bacterial microbiomes together with microeukaryotes in wild marine hosts was to me a unique and exciting opportunity.

My role within the project included the characterisation of loggerhead-associated bacteria and diatoms by culturing and DNA sequencing. It took hours and hours of microscopy before I would get lucky (or skilful enough, or both) and isolate my first diatom and grow it in culture. My supervisor knew from her own experience how important it is to have a strong network of fellow researchers to learn from, so even though I had just started to figure out this diatom thing, she did not hesitate to throw me into different research visits, conferences and workshops almost immediately. Within the first year of my PhD, I visited Ghent (Belgium) and Naples (Italy) to learn more about different methods, changed the initial direction of my research, and presented my first poster. The incoming loggerhead sea turtles were happily sampled, and I had already started to apply for additional research grants to expand my skills.

The bubble I lived in would soon burst and require a different set of skills, mostly in the categories of adaptability and resilience. In March 2020 the city of Zagreb was hit by an earthquake as well as being in the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the moments of jumping out of bed, gathering loved ones, pets and necessities, and feeling the deep vibrations of the earth moving beneath one’s feet, I forgot about my research or the threat of coronaviruses. After the initial shock, my colleagues and I discovered that our workplace was seriously damaged. In the following months, as we scrambled to pick up the pieces (pun intended), I believe we discovered skills we never knew we had or thought we needed.

The initial ‘fast and furious’ approach to my research helped establish collaborations for this difficult period. I was happy to receive Assemble Plus TA and FEMS Research and Training grants to visit Ghent again but for a longer period. With the support of Prof. Vyverman and Prof. Willems I could build on the research started back home in a safer environment. Due to lockdowns, I didn’t get to experience the full academic or social life in Ghent, but I did receive priceless support from people working alongside me.

Everything sped up In the last two years of my PhD studies, as if trying to catch up the time lost the year before. To me, it seemed the transition from online to in-person conferences and workshops happened in a blink of an eye. I could finally present my data on physical posters and during lectures where I could see the audience – it was terrifying and exciting at the same time. The gut bacterial communities of loggerheads saw the light of day both in conferences and as a research article, while the knowledge gathered from the earthquake-struck but well-travelled diatoms was published here and here shortly before my dissertation defence.

As a freshly baked PhD I do not know yet what the future will bring. The research I have done in the last few years has been rewarding but challenging on its own (as academia often is) and did not need additional natural disasters. I do hope that the hardships endured by researchers across the globe in the last few years have equipped us all with valuable experience for anything that we might face in the future.

No comments yet