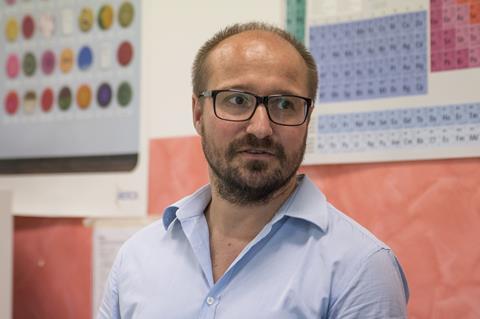

To his great surprise, microbiologist Frank Maixner found himself turning his scientific skills to mummy research. He reveals what the latest techniques are uncovering about ancient humans, the history of malaria and the Medici family.

Many of us grew up wanting to become an elite footballer, or a circus contortionist, or an alien investigator, but were forced to moderate our ambitions to something more realistic.

But for Frank Maixner, it was the other way round. He started off wanting to become a microbiologist - and unexpectedly ended up with a career as a mummy researcher.

In his role as coordinator at the Institute of Mummy Studies at Eurac Research in Bolzano, Italy, not only has he investigated the world-famous Ötzi, aka the Iceman, the natural mummy discovered in the Alps of a man who lived between 3350 and 3105 BC, but he has gone on to reveal the secrets of a whole cohort of Bolivian mummies and discovered that the mummified remains of the Medici family in Italy contained signs of malaria.

Career path

Dr Maixner reveals his peculiar career path - training as a microbiologist at the Technical University of Munich before studying microbial ecology in Vienna for his PhD and then spotting the job ad that was to shape his future.

“They were searching for a person to build up this so-called ancient DNA laboratory, focusing on the biomolecules which are still present in ancient human remains. This is how I came to this actually - it was not my aim from the beginning!” he says.

One of the very first projects he worked on at Eurac Research was the Iceman, which was discovered in September 1991 in the Ötztal Alps at the border between Austria and Italy and is Europe’s oldest known natural human mummy, offering an unprecedented view of Chalcolithic (Copper Age) Europeans.

Murder in the Alps

Ötzi is believed to have been murdered, due to the presence of an arrowhead piercing his left shoulder, along with other wounds.

One significant find was that his stomach was completely full - initially it was thought to be empty but the stomach was later found to have moved up towards the ribcage, detected in a re-evaluation of one of the radiographic images.

“I was participating on the sampling campaign, and afterwards I analysed the contents and the stomach tissues of this mummy - so that was the starting point,” Dr Maixner says.

“First we searched for traces of the pathogen Helicobacter pylori, and this became one of our studies. So it was not in the stomach wall any more, because over time, all the cells get lysed and the biomolecules just penetrate into the stomach content. But there was sufficient DNA present in the stomach content to reconstruct this genome and we compared it to modern diversity.

Dissecting the final meal

“The other project was the reconstruction of his last meal. It was composed of wild animals like ibex, a mountain goat, and red deer was also part of his meal and then he had this very early form of cereals called einkorn and some toxic bracken fern.

“So that was the initial starting point of my studies here and it laid the base for the methodological way that we approach those samples, which is quite different to modern samples. First of all, these samples are very precious and so you can’t just go back into the lab and regrow an organism and try it again. You need to be quite clear that this is cultural heritage.

“And if we extract DNA, for example, already the extraction is a little bit different - so you go for minute amounts of highly fragmented DNA, with mean fragment lengths of around 50 bases which is quite different to modern DNA.

“And then you normally cannot use any more PCR-based analysis, because it’s just too fragmented, so you immediately go into next generation sequencing methods, for example, and you do a so-called metagenomic analysis.”

The little that remains

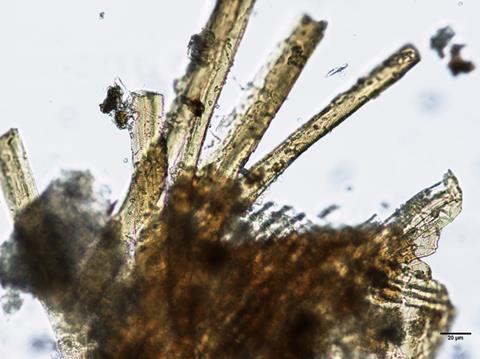

The same holds true for the microbiological analysis as well, he says - when carrying out microscopic analysis, it’s often only the collagen elements that remain, while the cellular content has been lysed.

“It’s often only the most rigid part of the proteins that survives, so you get a first impression of tissue, but often you cannot assign the tissue - that’s the problem we have,” he says.

Dr Maixner says he is currently interested in learning more about the microbial composition of mummies, including the gut contents - sometimes traces of the microbiome are still present after all this time.

“We work with so-called paleofaeces material, for example, which seems to be quite well protected from external contamination and still resembles quite nicely the original composition,” he says.

Salt mine remains

Recently the team published their analysis of paleofaeces material from a salt mine in Hallstatt which has been used by humans for 4,000 years.

“By analysing this paleofaeces material, we saw quite distinct changes throughout time. We found higher diversity in the past, more of the original community composition which resembles much more what we currently still see in the so-called non-westernised societies,” Dr Maixner says.

“And this was the case up to Baroque times - we assume that from the few samples we have analysed so far that it’s most likely that the major shifts in the microbiome occurred afterwards during industrialisation, and this is an ongoing discussion currently.

“I have to admit there are limits. Quite often we have samples which do not have any more biomolecules present, for example, plus there may be degradation. But in certain circumstances we can see and we can combine this dating with the presence of still so-called endogenous DNA.”

Bolivian mummies

Most recently the team has been working in Bolivia on six mummified bodies that are stored in the National Museum.

“With the analysis we have been doing, we have been able to bring them more information that can put them into better context and allow them to be put on display again,” Dr Maixner says.

“We try also to help them find the right conditions for future conservation.They’re all pre-Columbian mummies and very well preserved.

“So one thing we are trying now is not only the microbial part but also the human part, to bring them into the context of the Bolivian region, comparing them to other indigenous populations. In parallel, we are currently reanalyzing the gut contents of these mummies.

High Andes adaptations

“We have an interesting project ongoing, since in this region of the high Andes indigenous populations are extremely exposed to higher arsenic loads. There’s a group which is analysing the modern gut contents of those indigenous populations that face this arsenic load to better understand why they can cope with this. So we are now trying also to look into these mummified remains to see whether this adaptation was present already.

“There seems to be an adaptation on the human genomic level, so that certain regions in the genome seem to have an advantage. But there’s also the suspicion that the gut microbiome also helps to detoxify so many components, so this is one thing we’re also currently working on.”

The Medici tomb

The team’s most gripping recent published study was the discovery that the pathogen linked to the most deadly form of malaria had been dentified in mummified soft tissue belonging to members of the Florentine Medici dynasty.

The notorious dynasty buried its dead according to a special ritual - during embalming, the entrails were removed and placed in large terracotta vessels called orci which were buried together with the coffins in the Basilica di San Lorenzo in Florence.

In 2010, researchers were allowed to sample nine of these orci which were decorated with the family’s coat-of-arms. Of the nine, two bore the names of specific family members.

Mummified tissues

Some of the mummified fragments resembling pieces of cloth turned out to be mummified tissues. Molecular analysis didn’t yield much information due to degradation of the materials, repeated flooding by the River Arno and temperature fluctuations, but Dr Maixner discovered some interesting patterns within the microscopic structure.

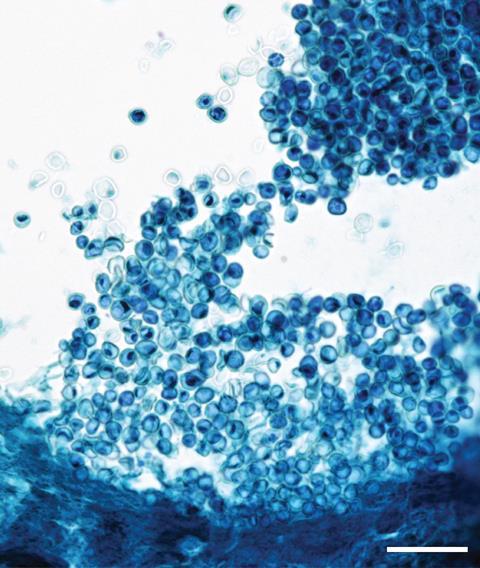

Thin tissue sections revealed a potential blood vessel that still contained collections of red blood cells. When a method called Giemsa staining was used, evidence of a parasite inside these blood cells was revealed.

“It was only in one or two cases that it was possible to see some structures which could resemble a blood-carrying material or at least some blood-carrying tissues and on top in these pictures we could see structures resembling red blood cells - and this was quite an unexpected finding, I have to say,” Dr Maixner says.

“So it was done by classical histological analysis, and then we moved on and used Giemsa staining - it turned out that within these erythrocytes there were also still also structures which could be stained and we really invested more in understanding what this was.

Probing the surface

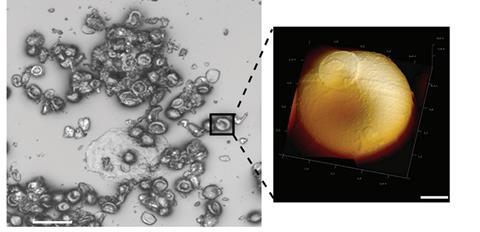

“One of the techniques we used is called atomic force microscopy, where you just analyse the surface on a micrometre scale and this confirmed the size and shape of erythrocytes. But interestingly then, on top we also saw ring-like structures. There are two parasites known so far which can form these ring-like structures in one of their developmental cycles - Babesia and also Plasmodium.

“So we used antibody antigen staining and this revealed that we clearly had parasites of Plasmodium falciparum.

“We tried in parallel to confirm it in another way using DNA, which could maybe allow us to place it in the phylogenetic framework, but unfortunately, it turned out that these biomarkers were highly degarded and weren’t present anymore.

Proteins and sugars

“So what we know now with all these analyses is that proteins are more stable and survive longer, so there are still antigen structures which can be targeted.

“We also collaborated with people from Asia who are quite good at analysing glycans - sugar molecules on the top of proteins. So their analysis supported the presence of interesting glycans which are known to be on the surface parasites, but what they could also show was glycan structures on top of the erythrocytes which could allow us to identify even the blood group of these erythrocutes - they turned out to be Group B.

“So you can see how much information you can still extract from these remains just by using microscopy and some chemical analysis.”

Returning to the orci

The new findings could potentially open up doors to discover more about the Medici samples, Dr Maixner adds.

“This is something I would like to do - go back to the samples we took at that time, 10 years ago, and which are still in our institutes.

”There are some interesting structures we have not yet looked at, actually, and I would like to to see whether we could see further indications for malaria in those structures,” he says.

Archaeology of malaria

“I think with this knowledge we have gained, we should definitely extend this to other samples coming from different regions in Europe, since there’s still too little knowledge about how far north malaria was present, for example, during mediaeval times.

“There are some indications for sure and some historical reports, but I could imagine that especially having access to church mummies, for example, there could be a good chance to use the same method to identify more cases of malaria. This would really be nice in the context of better understanding the prevalence and occurrence of malaria during the mediaeval time in Europe.”

Confounding the sceptics

Initially, Dr Maixner says, there was a lot of scepticism that using endogenous DNA would work in these investigations.

“That work just started at a time when a lot of DNA still was amplified using PCR-based methods and the risk of contamination was extremely high,” he says.

“I think the biggest surprise was when I identified the ibex in the stomach content and this told me okay, this cannot be a contamination. This was my biggest surprise, I have to say.

“Now, with these new techniques, we have different authentification possibilities, so we can now look for damage patterns, for example, which accumulate over time in the DNA, and gives us very good proof that this is actually really ancient, not modern contamination.

“But, this was definitely the point from which I really believed in what I’m doing - coming from modern DNA, you are really used to working differently.”

Topics

- Applied Microbiology International

- atomic force microscopy

- Babesia

- Basilica di San Lorenzo

- Be inspired

- Community

- Eurac Research

- Frank Maixner

- Giemsa staining

- glycans

- Gut Microbiome

- Hallstatt

- Helicobacter pylori

- Iceman

- malaria

- Medici family

- Metagenomic

- Microbial Genomics

- mummified

- One Health

- Ötzi

- paleofaeces

- Plasmodium falciparum

- Technical University of Munich

- UK & Rest of Europe

No comments yet