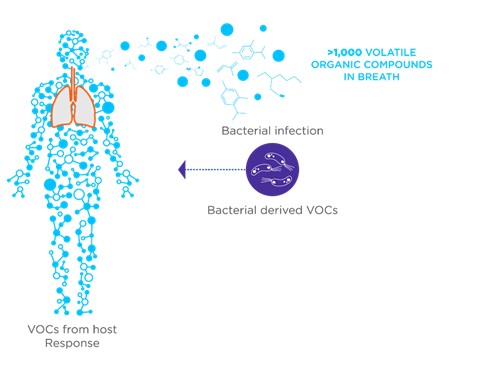

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are a diverse class of carbon-based molecules that are gaseous at room temperature and are detectable in exhaled breath, urine, and feces. VOCs can originate from human metabolic processes within the body (endogenous VOCs) or external sources such as diet, prescription drugs, microbial metabolism, and environmental exposure (exogenous VOCs).

The role of VOCs in health and disease is garnering increasing attention, particularly in their use as biomarkers for a wide range of medical conditions, such as diabetes, lung conditions, cancer, gastrointestinal diseases, and infections. In infectious diseases, VOCs can originate from metabolic disruptions caused by pathogens or from the metabolisms of the pathogens themselves. This dual origin highlights VOCs as an invaluable tool for the early detection and monitoring of infectious diseases.

Breath-based diagnostics offer several advantages over other sample matrices

Among the various approaches for VOC detection, breath analysis is a particularly attractive option, with breath-based diagnostic tests offering several advantages that make them suitable for clinical use. Breath analysis is non-invasive, meaning that, unlike blood tests and biopsies, collecting a breath sample is painless and simple. This significantly improves patient comfort and compliance, particularly in vulnerable populations such as children and immunocompromised patients who may be more sensitive to invasive techniques. Traditional diagnostic methods for infectious diseases often involve microbial cultures which require days or even weeks to produce results. For example, Mycobacterium (the bacteria that causes tuberculosis) is a slow-growing bacteria and can take between 6 and 8 weeks for a culture to produce a result that can be reported to a physician. In contrast, for an average person, their total blood volume circulates through their lungs every minute, meaning that a breath sample taken over a minute is enriched for compounds that have originated from the entire body.

Breath is an inexhaustible resource compared to other sampling methods such as blood tests; breath is produced constantly from the body and can be collected in large volumes. The compounds found in breath samples can be pre-concentrated before analysis, enabling repeated or continuous measurements to assess a patient’s condition, opening the potential for real-time monitoring. This positions breath analysis as a technique that can be used to monitor disease progression, evaluate treatment response, and detect signs of reoccurring disease. Breath VOCs reflect real-time metabolic activity as the products of metabolism pass straight into the bloodstream, and into the breath, from their generation throughout the body, in a matter of minutes. It can take hours/days for this process to happen and be reflected in other sampling mediums such as feces. Analysing VOCs in breath allows for tailored diagnostic and treatment strategies, aligning with the growing emphasis on personalised medicine. Breath analysis also provides an opportunity for rapid, point-of-care devices to enable quick diagnosis in clinical settings, which is particularly advantageous in remote locations and regions with poor health infrastructure.

The role of VOCs in infectious diseases

An infectious disease is defined as an illness caused by a pathogen or its toxic product. These diseases arise through transmission from an infected person, infected animal, or contaminated object to a host. Infectious diseases are responsible for a large proportion of the healthcare burden that impacts economies and public health systems across the globe, particularly affecting vulnerable populations. Tuberculosis (TB), malaria, diarrheal diseases, and lower respiratory tract infections are among the top causes of overall global mortality. In a healthy individual, the day-to-day composition of VOCs in breath, resulting from basic metabolic and microbiota activity, remains relatively consistent. Changes in the abundance of specific VOCs found in exhaled breath can therefore be indicative of disease.

In the case of infection, pathogens can alter the host’s metabolic pathways, including immune response and inflammation of the affected tissues, to generate unique by-products. Certain pathogens such as bacteria and fungi, produce specific VOCs resulting from their own endogenous metabolic processes. These pathogen or disease-specific VOCs provide an avenue for rapid, precise, and non-invasive diagnostics. For instance, bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Mycobacterium tuberculosis produce distinctive VOC profiles that can be detected non-invasively in the breath.

Translating VOC research to humans through mouse models

Despite pathogen-specific VOC profiles being detectable in breath, there are significant challenges in bridging the gap between VOC biomarker research and clinical application. One obstacle is the variability of VOC profiles between individuals due to factors such as age, diet, environmental exposures, and genetics. These factors can influence VOC profiles making it difficult to identify accurate biomarkers of health and disease. Techniques such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) are highly effective at analysing VOCs in breath, however, they are too expensive and complex for routine clinical use. Portable VOC detection systems would help address this challenge, but these are difficult to develop without confidently validated biomarkers. Researchers turn to preclinical models, such as mouse studies, to better understand the mechanics and diagnostic potential behind VOCs.

Mouse models offer a controlled environment in which variables can be tightly regulated, providing valuable insights to further inform human studies. They also provide an opportunity to understand the origins of breath VOCs. For example, by matching exhaled breath VOCs between germ-free mice transplanted with different gut bacterial species to those detected in the respective in vitro cultured bacterial species, researchers can confirm the link between VOCs detected in breath and the specific gut bacteria that produce them.

In the context of infectious diseases, specific pathogens can be introduced into mouse systems, and changes in VOC abundance can be observed under highly controlled conditions. This allows for the identification of disease-specific VOCs that might be masked by the complexity of human heterogeneity. Another advantage of mouse models is that they allow for longitudinal studies, as researchers can track changes in VOCs over the course of an infection. This is particularly useful when studying long-term infections or the development of drug resistance, to identify biomarkers for drug efficacy. Large cohorts of mice can be studied simultaneously, allowing for the development of datasets that can improve the accuracy of VOC biomarker identification. Genetic modifications in mice allow researchers to study specific metabolic pathways involved in the production of VOCs, highlighting the mechanisms that link infections to VOC profiles.

Mouse models bridging the breath research gap in cystic fibrosis

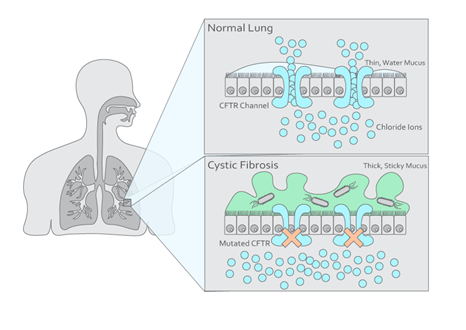

Infections of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the respiratory tract of patients with cystic fibrosis, a progressive, inherited disease, are associated with a decline in lung function and increased morbidity (Figure 2). Monitoring of P. aeruginosa infections is based on microbial sputum cultures, which are difficult to obtain from patients who are young, old, or have reduced sputum production. Alternatives to these cultures include throat swabs which are less sensitive, or bronchoscopy which is highly invasive. Additionally, the results from sputum cultures can take up to one week, causing a delay in the treatment process of a P. aeruginosa infection.

Breath analysis provides a non-invasive alternative for microbial cultures, as VOCs in breath can originate from either host metabolism in the lung or microbial metabolism from P. aeruginosa. Research has demonstrated the utility of human breath analysis in identifying cystic fibrosis-related infections. Targeted breath analysis has been used to identify P. aeruginosa infections in cystic fibrosis patients. Three VOCs were associated with P. aeruginosa infection in children, including 2-butanone, ethyl acetate, and 2,4-dimethyl heptane. Ethyl acetate demonstrated the highest predictive value (86%) for P. aeruginosa infection in both children and adults; the presence of ethyl acetate was inversely related to infection, suggesting that whilst other bacterial species such as E. coli produce ethyl acetate, P. aeruginosa produces enzymes that break the compound down. This highlights ethyl acetate as an important candidate for clinical use in the diagnosis of P. aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis patients. Other VOCs have been identified in studies that have an association with cystic fibrosis, including ketones, aldehydes, alcohols, carboxylic acids, and more.

Some unknowns regarding the detection of P. aeruginosa infection through exhaled breath include different strains of P. aeruginosa sharing the same “breath-print”, and whether potential VOC biomarkers in exhaled breath during bacterial infections originate from the host’s immune response or bacterial metabolism. These questions are more easily addressed through in vivo studies using mouse models. One recent study explored exhaled breath VOCs in mice infected with four different strains of P. aeruginosa. The analysis identified ten discriminatory compounds capable of showing a certain degree of strain specificity. Additionally, the study examined the origins of host VOCs by inoculating mice with UV-killed P. aeruginosa. By excluding metabolites produced by live P. aeruginosa in exhaled breath, the results highlighted certain compounds potentially originating from the host, while compounds more prominently detected in the live-group infections were likely produced by P. aeruginosa or derived from host-pathogen interactions.

Mouse models bridging the breath research gap in tuberculosis

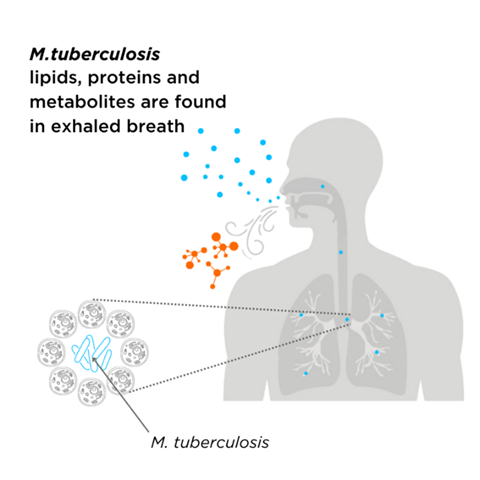

Tuberculosis is a serious global health threat, with one in four people across the world known to be infected with Mycobacterium Tuberculosis (M. Tuberculosis). Tuberculosis causes around 1.5 million deaths every year, meaning that, despite being both preventable and curable, tuberculosis is the world’s top infectious killer. Up to 15% of infected individuals are likely to develop active tuberculosis during their lifetime, with immune-compromised individuals having a higher risk of falling ill. This highlights the need for high-quality tuberculosis screening and early diagnosis of disease. Blood tests can identify if a person is carrying M. tuberculosis, but cannot identify active, and therefore, infectious tuberculosis. This results in further tests such as CT scans and sputum sampling, which are expensive and invasive procedures. A non-invasive test to diagnose tuberculosis earlier is needed to help tackle this serious disease.

Studies have investigated the potential use of non-invasive breath analysis for tuberculosis diagnosis. A study by Phillips et al. analysed breath VOCs in patients with active tuberculosis to identify breath biomarkers of the disease (Figure 3). VOCs identified in this study included derivates of cyclohexane, benzene, decane, and heptane. These compounds are produced by oxidative stress from processes such as inflammation, so they are not specific to tuberculosis infection itself. However, benzene, cyclohexane, and 1-hexene were also found in the breath of tuberculosis patients and are structurally like VOCs previously observed as metabolites of M. tuberculosis in vitro, so they are more specific biomarkers of tuberculosis infection.

Due to the complexity and heterogeneity of human studies, the experiment by Phillips et al. is currently the only one that has attempted to establish a causative link between mycobacterial metabolism and pathogenesis through human breath analysis. While clinical studies on human breath are the ultimate step before developing potential VOCs into diagnostic tests, mouse models are more suitable for early discovery and mechanistic evaluation. These models are easier to manipulate for modeling different aspects of mycobacterial infections, employing genetically altered strains, or studying immune responses. A recent pilot study compared the exhaled breath of mycobacteria-infected and non-infected mice, identifying 23 key compounds that distinguish between the two cohorts. This ability to differentiate infected from non-infected mice using breath VOCs paves the way for the use of mouse models to address fundamental questions about tuberculosis and assess drug efficacy and vaccine performance.

Standardisation is the key to expediting translational research

While various methods exist for collecting mouse breath samples, such as using a nose-only inhalation tube or collecting breath from unstrained mice directly in a ventilated cage, a key limitation is effectively distinguishing baseline on-breath VOCs in healthy mice from background compounds. Recently, a novel pre-clinical method for collecting mouse breath samples in the laboratory was developed, focusing on enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio of breath VOCs. This method utilises modified gold-standard respiratory mechanics equipment (flexiVent®) with specific air filters. By collecting breath samples from intubated healthy mice onto industry-standard sorbent tubes, the method ensures minimal background influence. This study used three specifically defined metrics to calculate on-breath VOCs, providing a rigorous yet flexible approach for determining which VOCs are considered on-breath compared to background. Additionally, the study directly compared mouse and human breath by employing the same air filters, sorbent tubes, and analytical methods, identifying 49 analogous VOCs.

This innovative breath sampling method establishes a foundation for translating findings and biomarkers from preclinical mouse studies into human clinical studies. By manipulating variables such as pathogen strain, host response, and environmental factors, researchers can identify robust biomarkers that are likely to translate to human studies. Once validated, these VOCs can then be assessed in clinical settings and have the potential to advance diagnosis and treatment plans. This preclinical-clinical trajectory is vital for establishing the reliability of VOC biomarkers. The relationship between mouse models and humans also holds promise in drug development, as mouse models allow researchers to monitor the effects of treatment and observe their impact on the VOCs found in the breath, providing an indicator of drug efficacy. If candidate drugs produce the same VOCs in humans as in mice, it strengthens the case for clinical utility.

The future of breath in infectious disease diagnostics

The advantages of studying breath VOCs in mouse models are invaluable for advancing the field of breath research. By combining standardised breath collection methods, platform analysis, and precise on-breath calculation metrics, commonly identified VOCs between mice and humans can narrow down key compounds for translational research, effectively bridging the gap between in vivo and clinical studies. This approach accelerates biomarker development and lays the groundwork for creating point-of-care devices. The great promise of non-invasive breath VOC analysis for diagnosing and monitoring infectious diseases could revolutionise public health, offering a powerful tool for reducing transmission and improving health outcomes on a global scale.

Read more: The scent of infection: how smells can help us spot disease

No comments yet