Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has evolved into a complex global health issue which has outstripped the development of new antibiotics and therapeutic strategies. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates 1.27 million deaths were attributed to AMR infections in 2019. By 2050, 10 million deaths are predicted at a cost of $100 trillion to the global economy. Moreover, in the UK, it is estimated that the NHS spends up to £180 million on AMR-related infections. Non-healing wounds, or Chronic wounds (including diabetic foot ulcers, venous leg ulcers, pressure ulcers, burns and surgical site infections), are a health and financial burden, with NHS costs ranging up to £5.6 billion. These wounds can be readily colonised and easily infected by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria.

Background and the problem

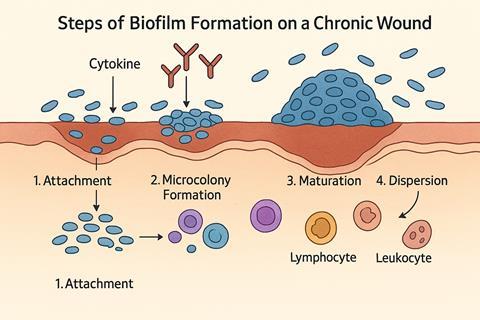

A primary pathogenic driver of these persistent infections is the establishment of biofilms. Transition from a planktonic state to a biofilm one is a complex multi-staged process involving surface adhesion, cellular proliferation into microcolonies, and eventually accumulating into a complex 3D mushroom-like structure with a network of water channels for nutrient and waste transport. Structural integrity is underlined by a matrix of proteins, microbial-produced exopolysaccharides, eDNA, and lipids known as the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS). This provides not only a protective physicochemical environment from host responses, environmental stress, antimicrobials, and competing species but also stabilises the 3D structure and promotes cell-cell communication via quorum sensing. The high cell density promotes horizontal transfer of resistant genes and, due to the heterogeneous environment, can encourage a phenotype that allows sessile cells to be resistant to antibiotics.

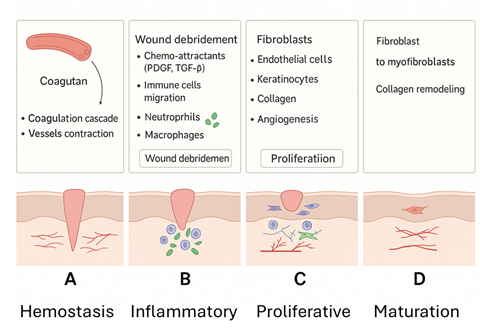

The continuous presence of a biofilm and its production of toxins and destructive enzymes within a non-healing wound inhibits and disrupts the normal healing process, resulting in a cycle of continuous inflammation and hyper-inflammation. For example, biofilms are capable of driving leukocyte recruitment and altering cytokine engagement, leading to chronic inflammation. Through persistent chemoattraction, inflammatory cytokines are released, delaying repair and causing tissue damage. In essence, wound healing becomes bacteria-centric rather than host-centric. Our aim is to provide a novel treatment strategy to target biofilm-related wound infections and allow the host’s physiological healing processes to resume centric control

The strategy

Bacteriophages (phages) are abundant and ubiquitous within the environment; they are viruses that specifically target bacteria. Phage therapy has a long history. Félix d’Hérelle was the first to recognise their potential, which in recent years has had a resurgence. The arguments for the therapeutic advantages of lytic phages within the context of chronic wounds are strong:

- Specificity: phages can have a broad and narrow range, which allows them to target specific bacteria and not harm the surrounding microbiome

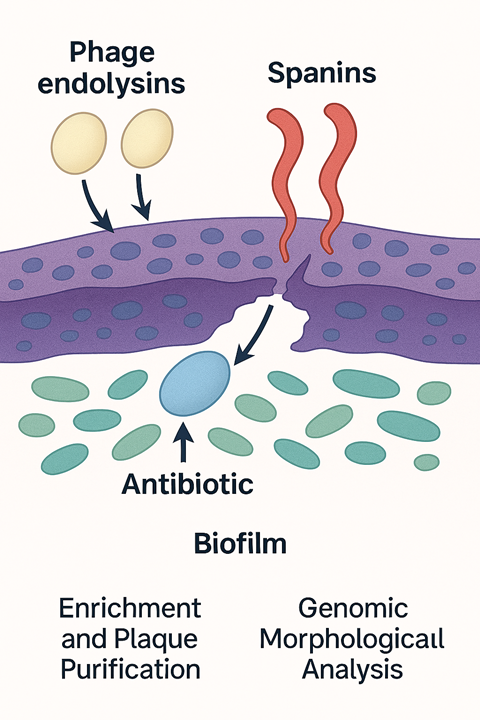

- Biofilm destruction: phages can express an arsenal of lytic enzymes, such as depolymerases, endolysins, spanins, and holins, that work in a coordinated manner, degrading the biofilm and components of the EPS.

- Phages can be delivered in highly localised doses, amplified at the site and are naturally cleared

- Phages can act with antibiotics in synergy to eliminate infection and be incorporated into biomaterials for wound management

- Antagonistic pleiotropy: the potential of phage steering

The translation of laboratory research to bedside treatment is still young, compounded by unique challenges, and treatment is only considered in special cases. To overcome this translational barrier, we at BCU (Birmingham City University) are developing two synergistic biobanks: a specialised AMR-focused phage biobank and a complementary tissue biobank to evaluate host-phage bacterial cellular interactions. The information gained will help to create a more realistic in vitro wound model and develop a therapeutic vehicle, such as a phage-antibiotic hydrogel aimed at clinical application.

Why build targeted AMR biobanks?

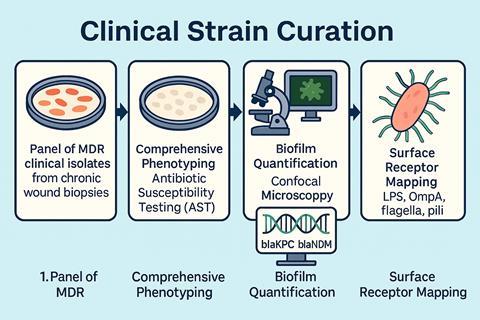

Our Biobank is constructed with disease-specific relevance and targets only AMR pathogens from chronic wounds. The foundation of the biobank is based upon a panel of clinically significant AMR Gram-negative and positive bacteria. These pathogens range from the categorised ESKAPE(E) organisms (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter, and Escherichia coli) to Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Citrobacter spp.

Many of these isolates are biofilm producers harbouring resistant markers such as extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) and carbapenem-resistant enzymes (CRE), as well as intrinsic resistant mechanisms such as aminoglycoside 6’N-acetyltransferase type Ib (AAS(6’)-Ib. The resistance profiles make these pathogens difficult to treat with conventional antibiotics and treatment.

Each clinical strain undergoes comprehensive phenotyping, biofilm quantification, genomic sequencing, and surface receptor mapping. This allows the biobank to reflect ‘real-world’ metadata of infection and pathogenicity.

Developing the AMR phage biobank

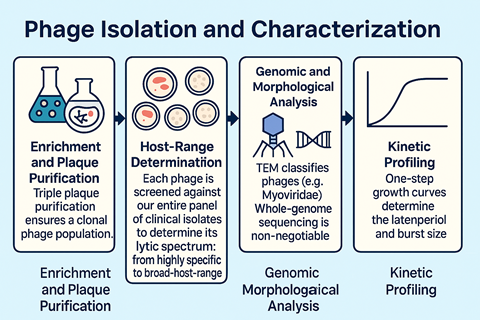

The majority of our phages were isolated from the River Chelt and the Avon. They were characterised via plaque purification, morphological assessment via electron microscopy, and host-range profiling against a panel of AMR strains. This process identifies phages with broad activity and high lytic efficiency. Each phage undergoes whole-genome sequencing to verify safety. Screening excludes temperate phage characteristics, lysogeny genes (integrase) and any isolates harbouring resistance, virulence toxins, and virulence factors. Environmental stress testing across temperature ranges, pH and storage diluents is undertaken. This provides crucial data for long-term biobanking and therapeutic formulation, and endotoxin analysis of the lysates is carried out to ensure safety.

One of the distinctive features of this biobank is its emphasis on biofilm-adapted phenotypes. Many wound-derived bacterial isolates are strong biofilm producers, so the biobank assesses phage efficacy in both planktonic and biofilm models using synergy screening with appropriate antibiotics, such as meropenem, gentamicin and vancomycin. The metadata produced allows us to assess the optimal potential of the phages as antibiofilm agents. This dataset transforms the collection into a functional infrastructure for future therapeutic development.

The tissue bank: decoding the host response

Phage–bacteria interactions are well studied; however, interactions between phage-bacteria and host responses still represent a major knowledge gap. To address this, we are establishing a tissue biobank that captures cellular and inflammatory biomarkers from various chronic wound models exposed to phage-infected AMR bacteria. Using fibroblasts, keratinocytes, endothelial cells and collagen wound models with young and old rat skin, we evaluate cell toxicity and viability, cell membrane integrity, inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α), healing marker (VEGF, MMP-9), tissue stress marker (ROS), and the transcriptomic responses.

The data produced enables us to build a reference database of host responses that can be linked to specific phages and bacterial strains. In translational terms, it advances the science of phage therapy by including a holistic clinical understanding of how phage therapy affects the immune system within a bacteria-centred process.

Developing a phage–antibiotic hydrogel for localised wound therapy

The ultimate goal of our biobank is therapeutic translation. To that end, we are developing an innovative, safe phage cocktail–antibiotic hydrogel capable of penetrating biofilms of chronic wounds for extended durations. One of our prototypes consists of sodium alginate and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) for moisture, viscosity, structural and biocompatibility. Genipen is introduced as a natural crosslinker and allows slow controlled release of the antimicrobial agents. An antibiotic of choice is added, followed by a cocktail of phages from our AMR-focused biobank, targeting a range of multi-drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria.

The gel demonstrated controlled release of both phages and antibiotics, effective inhibition and destruction of mature biofilms produced by Gram-negative bacteria through phage-antibiotic synergy mechanisms, in an in vitro model. It was non-toxic and demonstrated no harm to mammalian cell lines. In addition, it was mechanically stable and could be adapted to provide patient-specific therapeutics.

What’s going on

Phages have an arsenal of lytic enzymes. During infection, holins surround the inner bacterial membrane and form pores that allow phage endolysins to pass through and degrade the peptidoglycan cell wall. Spanins are activated and fuse the inner and outer membranes, creating a hole within the cell envelope that allows the release of phage progeny. With the biofilm structure disrupted, the antibiotic can now penetrate the heart of the biofilm without losing its potency and destroy the remaining bacteria.

Challenges and future directions

Despite early promising results, several factors need to be considered, such as the fact that the biobank is still in its early stages and could benefit from more AMR bacterial cultures and phages, thereby increasing the metadata framework. Further work is needed to optimise hydrogel performance under various chronic wound conditions, including analysis of appropriate swelling and adhesion in wound exudate. The tissue biobank will help characterise potential immune responses to phage-antibiotic combinations and support the development of safer biomaterials for topical treatment. In the context of the regulatory landscape for phage therapy, we are linking our metadata together to provide a transparent and reproducible framework that aligns with quality frameworks from the MHRA and EMA.

Conclusion

By developing a targeted AMR phage biobank combined with a cellular marker tissue biobank and phage-antibiotic hydrogel developmental pipeline, we have created a novel evidence-based, translational pathway strategy to combat the burden of disease caused by chronic wound infections colonised by MDR bacteria. The end goal is not only to reduce the disease burden but also to reduce the economic burden within the NHS. This integrated approach tries to bridge research and its effect on a real-world problem.

No comments yet