A new study led by a University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa researcher shows that avian malaria can be transmitted by nearly all forest bird species in Hawaiʻi, helping explain why the disease is present almost everywhere mosquitoes are found across the islands.

The research, published February 10 in Nature Communications, found avian malaria at 63 of 64 sites tested statewide, including areas with very different bird communities. The disease, caused by generalist parasite Plasmodium relictum, is a major driver of population declines and extinctions in native Hawaiian honeycreepers.

“Avian malaria has taken a devastating toll on Hawaiʻi’s native forest birds, and this study shows why the disease has been so difficult to contain,” said Christa M. Seidl, mosquito research and control coordinator for the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project, who conducted this research as part of her PhD at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

“When so many bird species can quietly sustain transmission, it narrows the options for protecting native birds and makes mosquito control not just helpful, but essential.”

Impact, spread of avian malaria

Avian malaria weakens birds by damaging red blood cells, often leading to anemia, organ failure, reduced survival and, in some species, death. For example, reports and studies have shown that mainly because of avian malaria, ʻiʻiwi or scarlet honeycreeper show a 90% mortality rate if infected, and the ʻakikiki, a Hawaiian honeycreeper endemic to Kauaʻi, is now considered extinct in the wild.

Unlike many diseases where only a few species play a major role in spreading infection, the study found that most bird species in Hawaiʻi—both native and non-native—are at least moderately capable of infecting southern house mosquitoes, avian malaria’s primary vector. Even birds carrying very low levels of the parasite were able to pass the disease to mosquitoes. As a result, many different bird communities can support ongoing malaria transmission.

“We often understandably think first of the birds when we think of avian malaria, but the parasite needs mosquitoes to reproduce and our work highlights just how good it has gotten at infecting them through many different birds,” Seidl said.

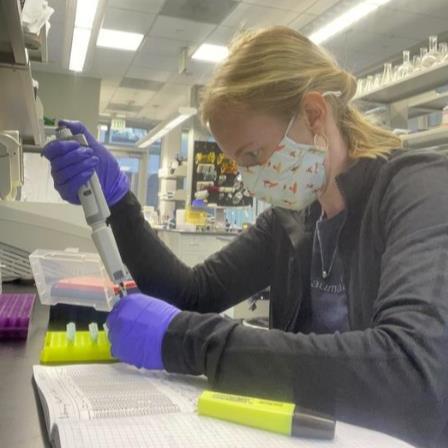

Blood samples

The study analyzed blood samples from more than 4,000 birds across Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, Maui and Hawaiʻi Island and combined the data with laboratory experiments measuring how easily mosquitoes became infected after feeding on birds. Researchers found that introduced and native birds often had overlapping levels of infectiousness, meaning both groups can contribute to disease spread. Also, because individual birds can harbor chronic avian malaria infections for months to many years, the researchers estimated this long period when birds are low to moderately infectious drives most of disease transmission.

READ MORE: Warmer Nordic springs double the incidence of avian malaria

READ MORE: Reduced movement of starlings with parasite infections has a negative impact on offspring

The broad ability of avian malaria to infect and spread likely explains why the disease is so widespread across the islands. The findings also suggest there are few, if any, mosquito-infested habitats that are free from transmission risk. To make matters worse, mosquito-free habitats are rapidly disappearing as warming temperatures allow both mosquitoes and avian malaria to develop in former refuges.

Birds, not mosquitoes

Seidl and the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project are part of Birds, Not Mosquitoes, a partnership of academic, state, federal, non-profit and industry partners facilitating mosquito control for Hawaiian bird conservation.

The Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project is housed under the Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit in the College of Natural Sciences. All birds featured were captured and handled in accordance with state/federal permits by trained ornithologists.

Photos and video (courtesy Christa Seidl and Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project) show laboratory work with mosquitoes central to the study, along with select field images; much of the research was conducted during the early pandemic.

No comments yet