Gastrointestinal tumors remain a global health challenge, with high incidence and mortality. Among them, colorectal cancer (CRC) carries the heaviest burden and serves as a key model for how the gut microbiota contributes to tumor development.

Traditionally, Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) has been viewed as the culprit behind antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis, but mounting evidence suggests its influence may extend beyond infection to promoting gastrointestinal malignancies.

READ MORE: Study reveals promising gut-targeted therapy for C. difficile infections

READ MORE: Scientists develop a way to track donor bacteria after fecal microbiota transplants

To synthesize this field, Professors Anhua Wu and Chunhui Li from the Center for Infection Control at Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, China, led a team that published a comprehensive review, “Clostridioides difficile: A Suspected Pro-Carcinogenic Bacterium for Gastrointestinal Tumors,” in the Chinese Medical Journal on November 20, 2025. The review proposes that C. difficile infection (CDI) may be a previously underappreciated pro-carcinogenic factor in CRC and possibly other gastrointestinal cancers, offering a fresh angle for research and prevention strategies.

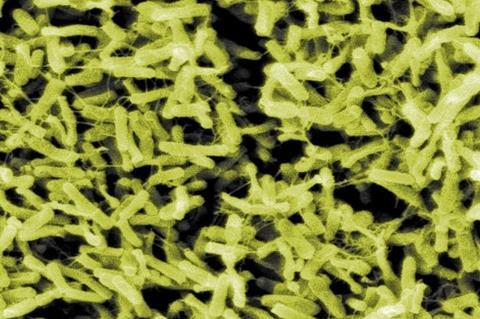

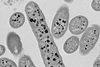

Snapshot of an anaerobe

The review first outlines the clinical and biological features of C. difficile, a gram-positive, spore-forming anaerobe whose spores germinate in the colon when the normal microbiota is disrupted, especially after antibiotic use. Its key toxins—TcdA, TcdB, and binary toxin CDT—damage the epithelial cytoskeleton, induce apoptosis, and trigger intense inflammation, leading to diarrhea, colitis, and a high recurrence rate that repeatedly injures the colonic mucosa.

Epidemiological data further link CDI to CRC: the incidence of both has risen in parallel. Patients with CRC—particularly those with impaired immunity—show higher C. difficile colonization, and the bacterium is more frequently detected in tumor tissue than in adjacent normal mucosa. Large cohort studies suggest that CRC is diagnosed more often in the years following CDI, and obese individuals with CDI are more likely to develop CRC than those without infection. Although these associations do not prove causality, they raise important questions about how CDI may reshape the colonic tumor microenvironment and promote malignant transformation.

Models of etiology

To frame these observations, the authors introduce several microbiological models of CRC etiology, including the alpha-bug hypothesis, driver–passenger model, keystone pathogen hypothesis, hit-and-run model, and common ground hypothesis. These conceptual frameworks describe how specific bacteria can initiate carcinogenesis, reshape the microbiome, or exploit tumor niches created by other factors. Within this context, C. difficile may function as a “passenger” that takes advantage of a susceptible mucosa and, through sustained inflammation and barrier disruption, accelerates malignant evolution.

Mechanistically, the review outlines seven interrelated pathways through which CDI may promote CRC development: toxic effects, pro-inflammatory responses, immune evasion, metabolic reprogramming, oxidative stress, cellular senescence, and biofilm formation plus microbial metabolites.

Although C. difficile toxins are not classical genotoxins, they generate reactive oxygen species that damage DNA, weaken the epithelial barrier, and increase exposure to carcinogens. Toxin-driven inflammation recruits neutrophils and myeloid cells, fosters IL-17-dominated immune responses, and supports a pro-tumorigenic milieu, while immune-suppressive remodeling—such as impaired anti-tumor immunity and altered eosinophil responses—allows transformed cells to escape surveillance.

Metabolic changes

The authors also emphasize that CDI can intersect with cancer-associated metabolic changes: early infection inhibits glycolysis and tricarboxylic acid cycle activity in host cells, pointing to metabolic reprogramming, whereas persistent oxidative stress and toxin-induced senescence of enteric glial cells drive chronic inflammation and DNA damage. In addition, C. difficile participates in complex biofilm communities on the colonic mucosa; these biofilms, together with altered bacterial metabolites like secondary bile acids and short-chain fatty acids, modulate immune surveillance, epithelial proliferation, and mutational burden.

Despite these converging lines of evidence, Prof. Li cautions that C. difficile should still be regarded as a “suspected accomplice” rather than a proven initiator of CRC. “Pinpointing where C. difficile fits along the continuum from dysbiosis and chronic colitis to neoplasia will require rigorous longitudinal and mechanistic studies,” he notes. “Priorities include defining CDI risk factors in susceptible populations, charting interactions between C. difficile and the tumor microenvironment, and determining whether CDI history should inform CRC screening strategies.”

The authors further suggest that C. difficile may also contribute to other gastrointestinal malignancies, including gastric, pancreatic, and biliary tract cancers. Expanding research in these areas could reveal novel microbial biomarkers and therapeutic targets. By reframing C. difficile from an infectious pathogen to a potential player in cancer biology, the review opens a new chapter in understanding—and ultimately mitigating—the carcinogenic potential of the gut microbiome.

No comments yet