Whether they’re there for a few days after a hospital stay, or living there long term, people in nursing homes are especially vulnerable to infections.

From bacteria that have evolved to resist most antibiotics, to common viruses that cause flu and COVID-19, microscopic threats can have a major impact on the health of these patients. They also spread quickly among people living and working closely together. A new guideline could help cut that risk, saving lives and money.

Based on the latest research, and backed by five major national professional societies, the guidance, published in the journal Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, lays out key steps that nursing homes can take to protect residents from infections.

Most importantly, the guidance calls for at least one staff member at each nursing home whose entire job focuses on infection prevention at every nursing home, as well as laying out guidelines for training, vaccinating, protecting and supporting clinical staff.

It also calls for more partnership among nursing homes and hospitals and public health agencies in their area, and for nursing homes to involve non-clinical staff in preventing infection too.

Home aspect

The guidance notes the importance of maintaining the “home” aspect of nursing homes and preventing social isolation while also preventing infection.

This includes allowing visitors and social and therapeutic activities even during outbreaks, while taking precautions to protect patients, staff and visitors during such times.

The guidance also addresses moderating the presence of medical supplies in patients’ personal rooms.

Lona Mody, M.D., M.Sc., led the writing of the guideline. She has spent more than two decades studying infection transmission and prevention in nursing homes, as a geriatrician and professor at Michigan Medicine, the University of Michigan’s academic medical center, and at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

No single magic bullet

“There’s no single magic bullet for nursing home infection prevention; all our interventions are multicomponent, and the whole is greater than the sum of its parts,” she said.

“The COVID-19 pandemic made the country realize that this is a sector that needs to be looked at just as we have done in hospitals for decades. We can’t just discharge hospital patients to nursing homes thinking everything will be fine – they need protection there too.”

READ MORE: Spread of AMR bacteria linked to patient hand contamination and antibiotic use in nursing homes

READ MORE: RSV vaccination in older adults with health conditions is cost-effective

Mody notes the importance of work started decades ago by her co-author Suzanne F. Bradley, M.D., a professor emerita at U-M and infectious disease physician with geriatrics training. She led infection prevention efforts at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, including its nursing home.

Nursing home changes

Bradley notes how the nursing home industry has changed just since the publication of the last guidance of this kind in 2008.

“An increasing proportion of hospitalized patients are now rapidly discharged while still requiring skilled medical care, and that care is typically provided in nursing homes,” she said.

“Residents arrive sicker and the overall care provided is increasingly complex. The recent pandemic has finally garnered national attention to the many challenges that nursing homes have faced over the years to prevent infections in the frail nursing home resident.”

She added, “We hope that this new guidance will speak primarily to the infection control practitioner who leads the prevention effort in nursing homes and provides an updated evidence-based discussion of major issues of the day, how to choose and prioritize interventions that have been shown to prevent infection, and what resources, personnel and may be needed to ensure a successful program.”

Dedicated infection prevention staffing

Since 2016, the Medicare system has required each nursing home to have a staff member designated as the lead for infection prevention and control.

But, says Mody, that often is just one component of the individual’s job. Other demands often take away from their ability to run an effective infection prevention effort.

The guidance specifically recommends that every nursing home have a person whose only job is infection prevention – and that larger homes should have more than one.

Preventing infections

That way, the individual can ensure clinical staff get trained in proper ways to prevent infections when they’re caring for vulnerable patients – a task that can be massive given the high turnover rate of nursing home staff.

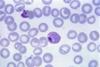

This can mean everything from cleaning skin and surfaces, to wearing protective gear during close encounters with people who have multidrug resistant organisms or MDROs, sometimes referred to as “superbugs.”

Many training resources are available from the organizations that endorsed the new guidelines.

Educating staff, patients and visitors on the importance of vaccination, and making vaccination easy for them to get, is another major focus of the guidance.

Stay off when sick

Another key area of education for staff: avoiding going to work when sick, whether because of their sense of duty to their patients or the financial need for a paycheck.

Mody’s own research informed the guidance on MDROs.

She and her team found that MDROs often travel with the patient from hospitals to nursing homes and tend to spread to areas beyond patient rooms to shared areas such as rehabilitation gyms and dining rooms.

Infections due to MDROs can be difficult to treat, and prevention requires multi-modal strategies that incorporate education, use of protective gear and diligent practice of core infection prevention practices by all including patients and visitors.

Urgent issue

The dramatic rise in short-stay post-hospital nursing home care coincided with the rise in MDROs, making this an urgent issue for nursing homes to tackle.

The new guidance includes information for testing and treating not only patients with MDROs but also using antibiotics carefully in other patients to avoid giving bacteria more chances to evolve resistance to the drugs.

The guidance also emphasizes the importance of nursing homes connecting with, and partnering with, the hospitals in their area and the public health agency that covers their city, county or region.

The COVID-19 pandemic made clear the importance of these ties, and of seeing nursing homes as a vital part of the ecosystem of health care, Mody said.

Similarly, within nursing homes, the guidance calls for infection prevention to be part of the job of facilities staff who monitor ventilation, custodial staff who clean various surfaces, and information technology staff who can make it easier for infection control staff to analyze and act on data obtained from digital patient records.

Not to be forgotten: patients and their loved ones.

Mody and Bradley say they should speak up about their concerns and take steps every day to clean hands, cover coughs, and report symptoms that staff can act on. Mody also recommends that nursing home residents and family members should ask about what precautions they should take to protect themselves or their vulnerable loved ones, including all available vaccinations.

The authors hope that regulators and health care quality reporting organizations will use the new guideline as a tool for ensuring nursing homes follow evidence-based standards.

More public reporting of infection-related quality measures could help patients and families choose nursing homes, too, said Mody.

Right now, the Nursing Home Compare tool from the agency that runs Medicare and Medicaid includes several infection-related measures, such as staff and patient vaccination and rates of infections acquired during a nursing home stay.

The business case

Though it might cost nursing home operators money to abide by the new guidelines, Mody says, the investment will pay off, as she and U-M colleagues showed through careful research.

“Preventing infection is the right thing for patients and for staff, and in the long run this will save money,” she said.

“The impact of prevention is never very visible, but in the end it translates to the business case too.”

The guidance is endorsed by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the American Geriatrics Society, and the Post-Acute and Long Term Care Medical Association.

No comments yet