Microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, can harvest crucial minerals from rocks and could provide a sustainable alternative to transporting much-needed resources from Earth. Researchers from Cornell University and the University of Edinburgh have now collaborated to study how those microorganisms extract platinum group elements from a meteorite in microgravity, with an experiment conducted aboard the International Space Station.

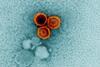

They found that “biomining” fungi are particularly adept at extracting the valuable metal palladium, while removing the fungus resulted in a negative effect on nonbiological leaching in microgravity.

The team’s study was published in npj Microgravity. The lead author is Rosa Santomartino, assistant professor of biological and environmental engineering at Cornell; Alessandro Stirpe, a research associate in microbiology, is a co-author.

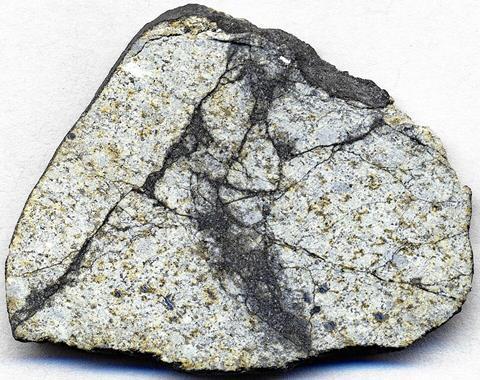

The BioAsteroid project, which was led by senior author Charles Cockell, professor of astrobiology at the University of Edinburgh, used bacterium Sphingomonas desiccabilis and fungus Penicillium simplicissimum to see which elements could potentially be extracted from L-chondrite asteroidal material. But understanding how the microbes interact with rocks in microgravity was equally important.

First experiment of its kind

“This is probably the first experiment of its kind on the International Space Station on meteorite,” Santomartino said. “We wanted to keep the approach tailored in a way, but also general to increase its impact. These are two completely different species, and they will extract different things. So, we wanted to understand how and what, but keep the results relevant for a broader perspective, because not much is known about the mechanisms that influence microbial behavior in space.”

READ MORE: The Space Microbiology Group

READ MORE: Exploring space from prison

These microbes are promising tools for resource extraction because they produce carboxylic acids, the carbon molecules which can attach to minerals via complexation and spur their release. But many questions remain about how this mechanism works, according to Santomartino, so the team also conducted a metabolomic analysis, whereby a portion of the liquid culture is collected from the completed experiment samples, and the researchers examine the biomolecules contained, specifically the secondary metabolites.

NASA astronaut Michael Scott Hopkins performed the ISS experiment, to test microgravity, while the researchers conducted their own control version in the lab, to test terrestrial gravity and compare these with the space results. Santomartino and Stirpe then analyzed the voluminous amount of data that was collected, which comprised 44 different elements, of which 18 were biologically extracted.

Microbial metabolism

The analysis revealed distinct changes in microbial metabolism in space, particularly for the fungus, which increased its production of many molecules, including carboxylic acids, and enhanced the release of palladium, as well as platinum and other elements.

In addition to aiding space exploration, applications could have terrestrial benefits, such as efficient biomining from resource-limited environments or mine waste or creating sustainable biotechnologies for circular economy.

Topics

- Alessandro Stirpe

- Bacteria

- bioextraction

- biomining

- carboxylic acids

- Charles Cockell

- Cornell University

- Fungi

- Healthy Land

- L-chondrite asteroidal material

- Michael Scott Hopkins

- Microbes and Space

- palladium

- Penicillium simplicissimum

- platinum group elements

- Research News

- Rosa Santomartino

- Sphingomonas desiccabilis

- UK & Rest of Europe

- University of Edinburgh

- USA & Canada

No comments yet